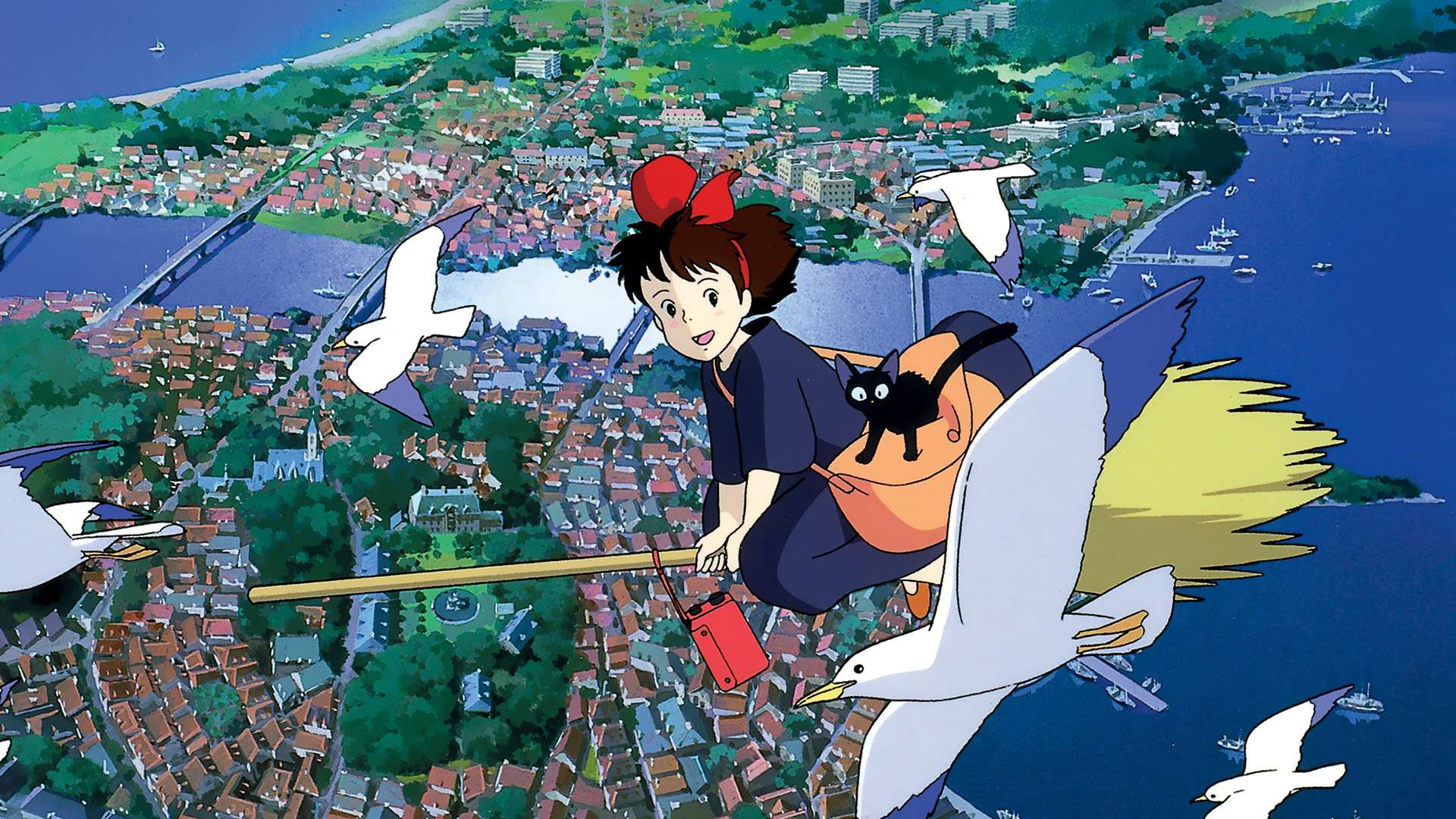

An Analysis of Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989): Kiki’s Delivery Service is an animated movie produced by Studio Ghibli and directed by its co-founder Hayao Miyazaki. The film is an adaptation of the novel of the same name by the author Eiko Kadono and was released in 1989 by the Toei Company.

Kiki, the main character, is a 13-year-old young witch. Traditionally, young witches her age must serve a year-long apprenticeship in an unknown town, where she also will settle. The seemingly simple coming-of-age story hides within itself a deep and insightful reading about the concept of maturing and becoming an adult.

Indeed, what we want to analyze in this essay is: what is the ultimate goal of the apprenticeship? Why does tradition stipulate it? Why does it have to last a year and take place, as pointed out, in a town where another witch has not already made a settlement? What indicates that the apprenticeship is “successful” or its purposes have been achieved?

The year of apprenticeship, as well as other rituals common in many existing traditions, represents (and it is easy to intuit) the transition from childhood to adulthood. It follows how the goal of the apprenticeship is no less than the attainment of a new stage of maturity and the acquisition of the title of ‘adult person.’

At the end of the anime, it is clear how Kiki has been successful in the task assigned to her by the apprenticeship and how the purposes of it have been successfully pursued. However, it is not in the final climax of the story (the rescue of Tombo) that Kiki achieves this, but gradually and almost unnoticeably throughout the duration of her entire journey. Although the girl’s maturation is apparent, what remains vague, and what the film attempts to answer, lies in which are the qualifications to be considered such. We must trace Kiki’s entire journey within the anime to answer this.

Kiki is introduced at the exact moment when she decides, one month ahead of the anticipated date, to leave in the evening for her year of apprenticeship. This is because, according to the radio forecast, the moon would be clear. The witch is determined to leave on such a night to ensure a safe journey aboard her flying broom. Kiki is excited at the idea of embarking on this adventure and, more importantly, of settling down in a big city by the sea, a dream she contrasts with her quieter country life.

Also Read: 10 Best Hayao Miyazaki Movies

Yet, Kiki’s flying trip turns out to be the opposite of what she had hoped for. First, she meets another young witch who reminds her how she needs to find her own “talent” in order to effectively fit into a town, something Kiki has not yet discovered. Soon after, a strong and unexpected storm forces her to find shelter on a freight train. These are the first and subtle occurrences that begin to deflect the reality of events, as much as the unpredictability of them, from Kiki’s fantasies.

The next day she finally reaches the beautiful town of Koriko, where no witch has settled yet. Before long, Kiki is in danger of being run over, called out by the police, and treated with distrust by the townspeople. Only Tombo, fascinated by her ability to fly, tries to approach her, but without success.

For Kiki, who wants to show herself as independent, Tombo’s attempt to help her represents an affront to her desire for autonomy, and accepting it would be tantamount to admitting that she cannot succeed on her own. Throughout the day, Kiki finds neither a place to sleep nor a place to work. She is desolate and dazed by how different reality is turning out to be compared to her imagination.

Fortunately, she encounters the baker Osono, who allows her to sleep in her attic in exchange for help in the bakery. It is thanks to Kiki’s innate kindness that this opportunity opens up.

It is interesting to open a parenthesis, both on the confirmation of Koriko itself as well as on the aforementioned need to find a city where witchcraft is not present. Koriko is somewhere between an invented city and a combination of existing cities. Although the main influences are Visby and Stockholm, glimpses of Paris, London, Lisbon, Naples, and San Francisco are recognizable.

One side of the city faces the Mediterranean Sea, while the opposite side faces the Baltic. The time placement is equally fascinating; the anime is set in an alternate version of the 1950s in which the two world wars did not occur. This allowed Miyazaki to depict a hypothetical past in which technology had not evolved as quickly.

The particular contextualization of Koriko enables the city to be “universal,” a place where anyone can find themselves and try to navigate, just as anyone faces the same period of transition that Kiki faces in the film. At the same time, it allows for an unprecedented discourse on the juxtaposition between tradition and technology and how technology is one of the elements that most disorient Kiki, who represents tradition instead. The absence of other witches in Koriko is necessary for depriving Kiki of a clear point of reference and emphasizing detachment from tradition.

Once she gets the job at the bakery, Kiki aspires to find her own talent so that other people (like Osono) may also “find her to their liking.” Since her only skill is flying, Kiki opens an express delivery business, offering to carry packages from one end of town to another by flying her broomstick.

In this phase of the movie, Kiki begins to interface with essential lessons: the need to adapt to the reality of the facts (as different as they may be from idealization), the importance of making the best of every situation, and of valuing what one has, no matter how small. At the film’s beginning, she does not particularly appreciate her ability to fly, only to discover it as a unique source of sustenance as much as a tool to help and approach people.

Most of Kiki’s deliveries turn out to be problematic; she is attacked by birds, loses cargo, and finds herself in adverse weather conditions. However, unexpected kindnesses from others help her get the job done. It takes one particular delivery to represent a crucial growth experience for the young witch: on the same day she receives an invitation to a party from Tombo, she is called by an elderly lady who is preparing a special dish to take as a gift to her granddaughter.

Finding the lady having difficulty using the microwave, Kiki helps her cook the dish in the wood-fired oven. So as not to be late for the party, she takes the dish flying under a violent downpour. Arriving at the niece’s house, she is scolded for arriving wet, bringing unwanted food, and being sent away.

Tombo gives up waiting for Kiki for the party, and she locks herself in her room, prey to a deep sadness. She has learned something hitherto unthinkable: kindness is not always reciprocated by as much kindness, efforts are not always rewarded, and people will not always wait for you.

The next day Kiki has a fever and abruptly walks away from Tombo for the umpteenth time, is no longer able to communicate with Jiji, and can no longer fly. She is alone, without family and friends. Her only talent has failed her, and it is no longer possible to carry on her delivery business.

Undoubtedly the greatest crisis faced by the little witch so far, that of Kiki, can be called a real depression; actually, it is her own sadness that fuels her inability to do things that were natural to her until the day before. This is the culmination of the film’s core: namely, the real challenge that the child who wants to become an adult must face. The challenge in question is recognizing one’s vulnerability and overcoming it.

Being vulnerable is an intrinsic element of growing up and being human. Maturity means recognizing and accepting it. From the beginning of the anime, Kiki has confused being an adult with being independent, repudiating the idea of being vulnerable.

Her vulnerability, however, made its inexorable way throughout the whole movie: in her inability to predict the weather conditions on the day of her departure, in her being alone and helpless in a new city, in her not knowing what her talent (and consequently her path) is, in the risk that, despite her goodwill, the work will not always run smoothly.

The vulnerability in discovering the unpredictability of others and discovering simultaneously that she needs them. The vulnerability of witnessing how things do not always go the way you want them to.

It is Kiki’s moment of greatest vulnerability, allowing her to finally face it and understand how it is also a fertile ground for self-discovery. The protagonist gets to spend some time with Ursula, a painter who represents an alternative, adult version of Kiki and who has already been confronted with the difficulties inherent in growing up. Ursula helps Kiki stop, reflect, and accept her difficult time, letting it flow.

This is the first time the witch accepts vulnerability, dissociating her value from her magic (which, for her, is the key tool for independence). Growing up, and maturing, no longer means surviving alone, but it means accepting life, in its good times and bad. Ursula is also the first person with whom Kiki genuinely opens up, finally welcoming a friendly and disinterested help.

It is in this part of the film that the true purpose of apprenticeship, and of what it means to settle “effectively” in a town, is revealed. Becoming an adult does not mean becoming invincible, much less stopping needing others.

Becoming an adult means finding a place in the world, making it your own, and using one’s dreams and aptitudes to contribute and make your part. And above all, becoming an adult does not mean being able to always stand on one’s own two feet, but understanding the need for the other, which, however frightening, is the greatest weapon against vulnerability.

Kiki’s rescue of Tombo is the final step in achieving maturity: that is, trusting the other. Tombo, a representation of this concept for the entire anime, finally stops being a source of fear for Kiki and becomes her first true friend. And it is in order to help Tombo, driven by his trust, that she finally regains her magic. Similarly, her relationship with Jiji is also recovered, albeit in a changed form. The two will no longer be able to communicate with human words, but, accepting the change, they will unite again as they were at the beginning of the journey.

The beautiful end credits show Kiki finally settling into the town, accompanied by the words of a sweet letter sent to her parents in which she declares that she is happy. Kiki has overcome the challenges of her year-long apprenticeship and has outgrown her childhood phase. Throughout the film, she establishes an almost unprecedented definition of maturity. Contrary to what she thought, being an adult is no longer a destructive concept of isolation, independence, and conflict.

It means “settling in a place and entering into harmony with it.” Cooperation, trust, and selflessness are the tools with which to deal with the vulnerability inherent in being more mature. In contrast to a more Western view, in which “making it” is synonymous with success, luck, ambition, and the ability to be better than the competition, what is expressed by Kiki’s Delivery Service is a much healthier and undoubtedly much nicer concept.