Though it may not carry the same sense of cultural prestige as its younger French sibling, the Palme d’Or, the Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion is nonetheless a towering marker of distinction, every year highlighting a prominent, daring instance of cinematic excellence (and also, for some reason, “Joker”). The longest-running of the revered European film festivals, Venice holds a certain position of seniority and, as such, those films bestowed the Golden Lion implicitly carry the marker of significant, trendsetting works in the field of arthouse cinema. With 80 editions of the festival in the can and the 81st on the horizon, the time is right to look at those 15 that stand out above the rest as the best Golden Lion winners of all time.

Special Mentions:

More than a fair share of Golden Lions have been awarded to filmmakers who have gone on to become absolute legends in the field, so honorable mentions should be given to the likes of Luis Buñuel’s erotic drama “Belle de Jour” (1967), Agnès Varda’s achingly humanistic “Vagabond” (1985), Gillo Pontecorvo’s politically stirring “The Battle of Algiers” (1966), Satyajit Ray’s trailblazing Indian drama “Aparajito” (1956), and Andrei Tarkovsky’s melancholy debut “Ivan’s Childhood” (1962). Not only significant for the names attached, these films each represent a distinct facet of their respective directors’ strengths—facets that would go on to color the rest of their careers. As for the new school, Mira Nair’s “Monsoon Wedding” (2001), Sofia Coppola’s “Somewhere” (2010), and Andrey Zvyagintsev’s “The Return” (2003) each denote landmark moments for filmmakers more than worthy to take up that coveted mantle someday.

15. The Wrestler (2008)

Darren Aronofsky is no stranger to either the Venice Film Festival or controversy. Still, while films like “The Fountain,” “mother!” and “The Whale” were met with mixed reception, “The Wrestler” proved to be the director’s most notable and worthy examination of human suffering. The instance in which Aronofsky’s brand of confrontational empathy was at its most searing and least exploitative, “The Wrestler,” won out in Venice not only because of the weakness of its competition—the most noted titles included eventual Best Picture winner “The Hurt Locker” and Hayao Miyazaki’s “Ponyo”—but also because it represented the zenith of Aronofsky’s capabilities as an artist.

Headed by a career-best performance from Mickey Rourke, “The Wrestler” exhibits a sensitivity towards its gruff protagonist that takes Aronofsky’s typically bleak approach without being entirely bereft of the humor that makes us human in the first place. As Rourke’s beaten eyes carry us through Randy “The Ram” Robinson’s plight for purpose at an age where wrestling is no longer a feasible (or safe) career option, the film duly translates the ecstasy he feels in the ring to properly translate the emptiness of his existence outside of it. Through Aronofsky’s uncompromising vision, “The Wrestler” brings tangible meaning to the struggles when the soul isn’t ready to listen to what the body has to say.

14. The Woman Who Left (2016)

Lav Diaz makes long films. I know that fact isn’t going to induce any spit-takes. Still, it bears mentioning, if only for the sake of grasping just how much of a hold the Filipino filmmaker has in Venice. Although most of his films are roughly the length of three or four of their competitors put together, he’s still found the space to be anointed in the race for the Golden Lion. One such occasion was with “The Woman Who Left,” a film that stunned the Venice jury, perhaps due to Diaz’s show of restraint; the film was only just shy of four hours long. Jokes aside, even for a Diaz agnostic (read: me), “The Woman Who Left” demonstrates a surprising amount of purpose in its pacing.

While Diaz usually suffers from clearly choosing his unreasonable runtimes first and then building films around them rather than vice versa, “The Woman Who Left” weaponizes its plodding pace as the basis of a simmering revenge tale. In so doing, the director is able to question the purpose of such a quest, forcing the audience to soak in the disarming tension between the silences. As far as Diaz’s projects go, “The Woman Who Left” is not only a fulfilling venture because of its (relatively) tame runtime but, more pertinently, because Diaz puts his runtime to effective use.

13. Still Life (2006)

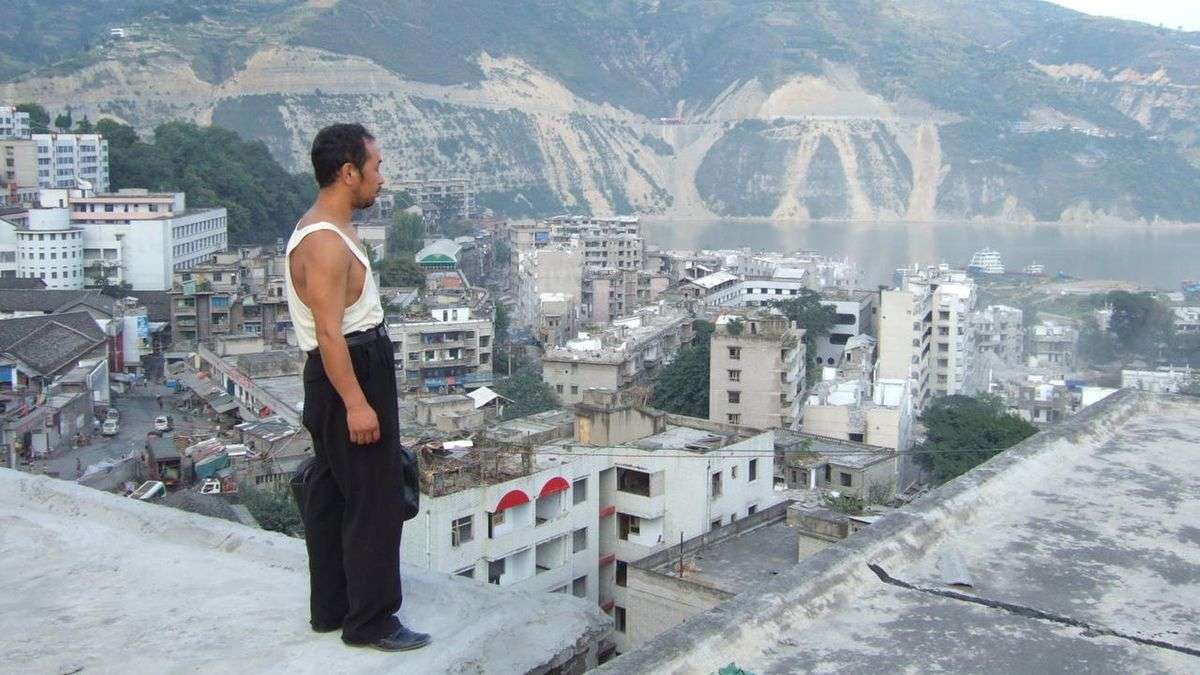

More of a Cannes regular than a Venice soldier, Jia Zhang-Ke has made a name for himself as one of the most patient, multi-faceted examiners of the rapidly changing face of modern China. “Still Life,” one of his very best, rightfully earned the director the Golden Lion due to its resonance, particularly in the wake of impending change along the famed Yangtze River. Split between two occasionally discombobulating storylines, “Still Life” paints a vivid portrait of modernity in motion, particularly with the noted tinge of mournfulness that comes when the old must be discarded to make way for the new.

The particular focus on the Yangtze and the demolition of the Three Gorges Dam proves to be the perfect feeding ground for the filmmaker’s musings on China’s path toward tomorrow, as the film’s distant characterization works in conjunction with the sprawling resonance of this moment in history for the nation’s populace. A worthwhile double feature with the documentary “Up the Yangtze” from the following year, “Still Life” takes on a slightly more oblique approach to reach similar conclusions, making effective use of Jia’s controlled pacing and heartbroken imagery to craft a vision whose heart beats all the louder because of how uneven its palpitations can be.

12. Vera Drake (2004)

Another director who probably feels more at home on the Croisette, Mike Leigh‘s portraits of unparalleled empathy have shaken audiences to their cores thanks to the uncompromising depth with which he examines his characters. “Uncompromising” is probably the most apt descriptor to use for a film like “Vera Drake,” whose empathy takes on new heights as Leigh examines a woman in early 20th-century England who assists young girls in performing illegal abortions. On this brutal emotional odyssey, Leigh pulls no punches in, showing where even the most well-intentioned actions can lead to disastrous consequences when the legal system is primed to lead the unequipped to inevitable failure.

Led by Imelda Staunton’s powerhouse performance (another Leigh staple), “Vera Drake” brings together Leigh’s two greatest strengths—his sympathy for his subjects and his rigorous attention to detail—for the sake of a desperately tangible examination of compassion in the face of tragic circumstance. All of Leigh’s films are a testament to the layers that compose each and every one of our lives. Still, “Vera Drake” is perhaps his most urgent examination of where those layers are forced to collide and when the horrors of systemic negligence force us to fade away.

11. Three Colours: Blue (1993)

Krzysztof Kiéslowski’s “Three Colours” trilogy (for the Americans reading this, yes, that’s the correct spelling of both the title and the word in general!) utilizes the shades of the French flag to unpack the three virtues embodied in the French Revolutionary ideals: Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. “Blue” takes on the first of those three subjects, as Kiéslowski looks at what happens when freedom is invoked as more of a curse caused by tragedy than from the personal choice to be unrestrained.

Juliette Binoche takes on the central role in what is—as one would expect—a performance of towering subtlety, portraying grief and existentialism in all their battling modes, all within the slightest flicker of her gaze. (For what it’s worth, “Blue” picked up the Volpi Cup for Best Actress alongside the Golden Lion.) Most of the best Golden Lion winners (including many of those mentioned above) achieve their success by way of examining the necessity of human sentiment, and this film embodies this notion with a visceral wholeheartedness that bakes itself right into Kiéslowski’s ethereal vision. An entirely European view of our often flagrant misunderstanding of the connections that keep us whole, “Three Colours: Blue,” and the following two films in its trilogy, project an almost otherworldly understanding of what it means to be a person.

10. Poor Things (2023)

In this, the unexpected period of unanimous praise for Yorgos Lanthimos—a period he seemed desperate to snuff out quickly with the gloriously alienating “Kinds of Kindness”— ”Poor Things” may very well represent the peak of the Greek filmmaker’s widespread success. Picking up the Golden Lion after only his second run in Venice, Lanthimos earned the accolade thanks to the perfect marriage of his oddball sensibilities with Tony McNamara’s eccentric screenplay. Coupled with Emma Stone’s massively captivating performance (do we sense a pattern here?), “Poor Things” again embodies humanity’s spirit, this time through a more overt (and playful) feminist angle.

If the world-building of “Poor Things” is impressive because of the immaculately detailed costumes and production design (both appropriately Oscar-winning), the film’s world feels just as vivid for the idiosyncrasies that Lanthimos sees fit to inject throughout the runtime, from the bouts of juvenile humor to the calculated cadence of his actors’ line deliveries. Through it, “Poor Things” never feels like an overthought exercise in prestige filmmaking, and to that end, the film brings a much-needed sense of color to the modern awards contender. A Golden Lion seems like just the reward for such an earnest endeavor.

9. Last Year at Marienbad (1961)

Likely the most challenging film to appear on this list, “Last Year at Marienbad” is one of Alain Resnais’s most celebrated films, a stark view of the elliptical potential of the French New Wave along the Left Bank. Much like its predecessor, “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” Resnais’s sophomore picture inhabits an overwhelming, dreamlike state that will put you in a trance if its exacting pace doesn’t send you reaching for the remote first. Resnais captures an almost surreal essence across its runtime, as the smooth camerawork creates a murky sensation, exerting complete control over the viewer’s experience.

Widely interpreted to be the story of a person recounting a recurring dream to someone else, “Last Year at Marienbad” feels appropriately jumbled and fluid in its portrayal of events, to the point where one can’t be sure whether they’re supposed to be enthralled or frustrated. But to that, Resnais asks: why not both? Though the Venice competition in 1961 found Resnais competing with the likes of Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, and Akira Kurosawa, it was “Last Year at Marienbad” that has stood the test of time as the most enduring of these titanic directors’ efforts that year (unless you want to entertain the “Yojimbo” argument, which I would gladly accept without debate).

8. The Green Ray (1986)

On a completely different current of the French New Wave from Alain Resnais, we have Éric Rohmer, whose examinations of human interaction were of a far different breed than those of Resnais or even his Right Bank contemporaries like Jean-Luc Godard; Rohmer’s films were of a more restrained, earthly nature and no film encapsulates the value of this approach more succinctly than “The Green Ray.” It is a film composed primarily of improvised conversations about life, love, and everything in between. The sense of purpose behind “The Green Ray” aches like an incessant sunburn, and it is just waiting to be remedied by the company of someone worth the affection.

What Rohmer understands best about people is our propensity to want contradicting things at the same time—to feel as if nothing in this world is ever good enough and to feel justified in that inherently unreasonable assessment. “The Green Ray” digs into this idea without ever looking down upon its very tangible protagonist, a woman whose impulsive behavior and overhanging sadness can only be perceived as a naked revelation of our struggles to find any true sense of happiness. As he was wont to do, Rohmer examines this messy facet of everyday life with great care and effortless zeal.

7. Short Cuts (1993)

Though a smattering of filmmakers have made it two-thirds of the way through the trifecta in any number of combinations, only two directors have ever won the Golden Lion from Venice, the Golden Bear from Berlin, and the Palme d’Or from Cannes. One of them is Robert Altman, and his Golden Lion came in the form of “Short Cuts.” (For those curious, Michelangelo Antonioni is the other and holds the additional distinction of also scooping up Locarno’s Golden Leopard for his mantle). The title, of course, is meant to be ironic, as the film’s many storylines intersect over just over three hours. But as with all of Altman’s best films, the runtime flies by thanks to his unmatched grasp of movement in both storytelling and people themselves.

Employing Altman’s typical methods of overlapping dialogue, “Short Cuts” gives its 22 principal characters the space to come to life (one would hope so with that length), and the director is given quite the menagerie of stars to round out his eclectic Raymond Carver adaptation. Matthew Modine, Robert Downey Jr., Frances McDormand, Jack Lemmon, and Andie MacDowell compose only a handful of the faces Altman shapes to his liking, and just as with any of his masterpieces from the ’70s, “Short Cuts” finds the American maverick embodying a truly madcap envisionment of his country.

6. Nomadland (2020)

2020 feels like an eternity ago, and with Berlin taking place just before the COVID pandemic began and Cannes bowing out entirely for the year, it’s easy to almost completely forget that Venice went ahead more or less as planned mere months into the decade-defining epidemic. That year, the Golden Lion went to eventual Best Picture winner “Nomadland,” a fitting choice that more or less encapsulated the restrained, disillusioned attitude that began to take hold once we learned that this pandemic would go on longer than “just two more weeks.” What shouldn’t be forgotten, however, is that Chloe Zhao’s film captured the moment without itself feeling like a hopeless slog, but rather for the sense of underlying drive for life in the face of changing fortunes.

Anchored by Frances McDormand‘s unwaveringly delicate lead performance, “Nomadland” speaks to a verve of living despite constraints, but Zhao never feels as though she’s ogling people experiencing homelessness—”I’m not homeless, I’m houseless; there’s a difference.” Touching on a deeply rooted understanding of why a person might be living in such situations (whether by choice or circumstance), “Nomadland” retains a spirited perspective on the roads we travel; whether set on these paths ourselves or by someone else, we make the most of the ride.

Also Related to Golden Lion Winners: All Guillermo Del Toro Movies Ranked

5. The Shape of Water (2017)

Everyone thought they were being so funny when Guillermo del Toro’s “The Shape of Water” began to make waves after its Golden Lion win; “It’s the movie about a woman who fucks a fish… are you laughing yet?” Those people began to feel pretty damn foolish (or justified, depending on where you land) when the film came out and took us by surprise with just how much depth and warmth del Toro managed to pull out of such an inherently goofy premise. Of course, it’s precisely del Toro’s enduring love for the monster films of his youth that drove him to imbue “The Shape of Water” with such a textured sense of genuine romance, proving that no premise is too silly if you genuinely care about it.

A towering achievement in nearly every crafts department—from its detailed sets to its meticulous makeup, from its gentle music to its loving performances— “The Shape of Water” proves that nobody onboard the film took this project as anything less than a proper display of passion from its architect, and that respect shines on the screen in every single facet. Del Toro got Hollywood and Venice alike to lament over a mute woman and an amphibian sea god… even without the lion-shaped trophy, that’s a pretty commendable achievement.

4. Roma (2018)

From one of the three amigos to another, Guillermo del Toro’s Golden Lion win was immediately followed up by his fellow countryman Alfonso Cuarón laying claim to the prize through his passion project, “Roma.” A story of a much more personal shade (unless del Toro is hiding something from us), Cuarón’s examination of his childhood housekeeper necessarily exists with a sense of white privilege towards his outsider view of this Indigenous Mexican woman. Still, “Roma” is aware of this gap and uses its existence to draw genuine understanding from this point of childhood obliviousness.

One of the most gorgeously shot films of the past decade (just another Tuesday for Cuarón), “Roma” takes a look at the mundanities of his housekeeper’s life as she experiences the joys and hardships of friendship, young love, and familial solidarity, all while she’s forced to come back to upper-class family’s home at the end of each day to pick up the toys, make the smoothies and sweep the dog poop out of the driveway. If “Roma” feels as though it is making light of Cleo’s existence, that’s only because Cuarón’s distant camera is staying true to the reality of his own dismissive treatment of her in life; “Roma,” however, finds a greater purpose to Cleo beyond her capacity to serve.

3. Lust, Caution (2007)

Ang Lee isn’t the only director to have won two Golden Lions, but he is the only director to have won two Golden Lions AND two Golden Bears (and he’s the only two-time Bear winner, at that). The second of Lee’s Venice prizes came in the form of “Lust, Caution,” a towering erotic period thriller acting as a testament to the Taiwanese filmmaker’s enduring versatility. A tightly woven narrative of historical struggle and simmering eros, “Lust, Caution” finds Lee at the top of his game, orchestrating a tense portrait of resistance in the form of sexual power.

Tang Wei leads the film with a dominating command of her skills as both a physical and emotionally driven performer, which makes her the perfect foil for Hong Kong legend Tony Leung Chiu-wai, whose effortless charisma helps to shape one of his rarer villainous roles. In “Lust, Caution,” sex isn’t a pleasure or even a weapon but a tool to be used with focused precision. Ang Lee understands this necessity with great clarity, and as a result, his first project in his native land since his American breakthrough proves that he hadn’t lost his edge, even when his examination of the domestic sphere involved taking on a much more… vulgar dimension than ever before.

2. Brokeback Mountain (2005)

Well, it didn’t take long to circle back to this one! Ang Lee’s first Golden Lion—coming only two years before the second— “Brokeback Mountain” has pretty much invariably solidified its position as a landmark film in the fields of revisionist Westerns, LBGTQ+ depiction, and just plain effective filmmaking. Having been discouraged by the critical failure of “Hulk” just two years prior, Lee’s near-retirement was halted by the encouragement of his father to pursue “Brokeback Mountain” as his next project, and the result was a heartbreaking tale of love in an impossible moment of time.

Perhaps the most incredible tool at Lee’s disposal here is his sense of tender restraint, which allows “Brokeback Mountain” to maintain a dignified respect for its characters that goes beyond the tragedy that risks defining them wholeheartedly. Even outside the periphery of this central doomed romance, the film is conscious of the effect this situation has on the families whose lives may be destroyed by this situation; to that end, Michelle Williams delivers one of her typically incredible performances to bring every ounce of truth to that sad reality. The pervading sense of melancholy throughout “Brokeback Mountain” has given the film a reputation for unrelenting bleakness. However, that shouldn’t deter anyone from experiencing one of this century’s most poignant instances of sympathetic filmmaking.

1. Rashōmon (1950)

Many believe the widespread Western embracing of Japanese cinema was kick-started when Akira Kurosawa’s “Rashōmon” won the Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival. Though such a direct claim can hardly be proven outright, the enduring legacy of Kurosawa’s masterpiece (just one of several) points to at least some level of credence, indicating that the credibility of both the film and Venice as an institution remains somewhat tied together. Regarding the movie itself, it’s no wonder why “Rashōmon” became such an overwhelming hit. With an innovative structure and compelling characters to drive it, Kurosawa’s steady direction ensures that the film never loses its footing in the potentially overpowering nature of its ambitions.

“Rashōmon” remains one of the most studied films in cinema history, but such lofty attributions shouldn’t obscure just how watchable the film actually is. As was always the case with the filmmaker, Kurosawa’s refined vision never came at the expense of a heartfelt story but instead found itself complemented by it; “Rashōmon,” therefore, proves to be an entirely compelling case of moviegoing homework that never feels like an obligation, but rather a privilege to experience for the first time. For that matter, experiencing the film for a second and third time also promises to be a rewarding experience, as the very nature of Rashōmon’s structure virtually guarantees that subsequent viewings will reward an observant, empathetic audience. A genre-defining masterpiece in every sense, “Rashōmon” almost single-handedly embodies everything the Golden Lion should represent.