Mrinal Sen will always be known as a Marxist artist. Right from being involved with the cultural wing of the Communist Party to his close association with the Indian Peoples Theatre Association, Sen confessed his dire need to involve political characters with social implications. Stumbling on a copy of Film Aesthetics, Sen started his journey as a medical representative, leaving it for a job in a Calcutta Film Studio as an audio technician. His first feature film “Raat Bhore” (1955) made him explore varied themes within his familiar middle-class environment. He was vocal against the excessive male chauvinism within highly industrialized societies and chose to be a ‘social agent’ rather than a preaching didact. His style was to provoke his audience, steering them toward a particular way of thinking, rather than offering a conclusive argument, leaving room for subversive creative interpretation.

The following is a comprehensive (although not exhaustive) list of the best films of Mrinal Sen. Throughout his career, Sen has been experimental with his mediums. This is an attempt to portray his oeuvre complete with jumbled storylines, montages, documentary features, mise en abyme, and cut-aways. In an interview with Chitra Subramaniam, Sen emphasized the futility of popular cinema over serious tasks. Comparing Virginia Woolf to the comics of Harold Robbins, Sen had persisted on the audience’s responsibility to do some ‘soul-searching’. Here’s hoping that this list could come in handy towards the same end.

10. Ek Din Pratidin (1979)

It is evident that Mrinal Sen does not admire middle-class virtuosity, and rightly so. It is in the alleyways of rusted debt traps, stagnant wages, rising living costs, and job insecurity that the vibrant rituals of a person’s life begin to wither. Perceiving the stunted development of a person, “Ek Din Pratidin” feels like a reiteration of pondering morals and piercing questions of freedom. A daughter fails to return one night. And one witnesses the fall of a century. Dependence, envy, complaints, laments, and presumptions – all crumble under the umbrella of toxic answerability.

Sardonically called “A Day Like Any Other,” this film won Sen the Best Director Award at the National Awards of 1980. With the likes of Ghatak’s “Meghe Dhaka Tara” (1960), Sen created his own signature of the breadwinning woman, that of an outbound victim. The noise around her absence is almost too loud to bear and all because she is the sole breadwinner of the whole family. Taking over the role of the ‘Man of the House’ comes with its own set of challenges and Sen made Mamata Shankar play in synergy. The yearning for light, love, and longing goes up in smoke as she observes the grandiloquence and fruitlessness of her efforts.

9. Mrigayaa (1976)

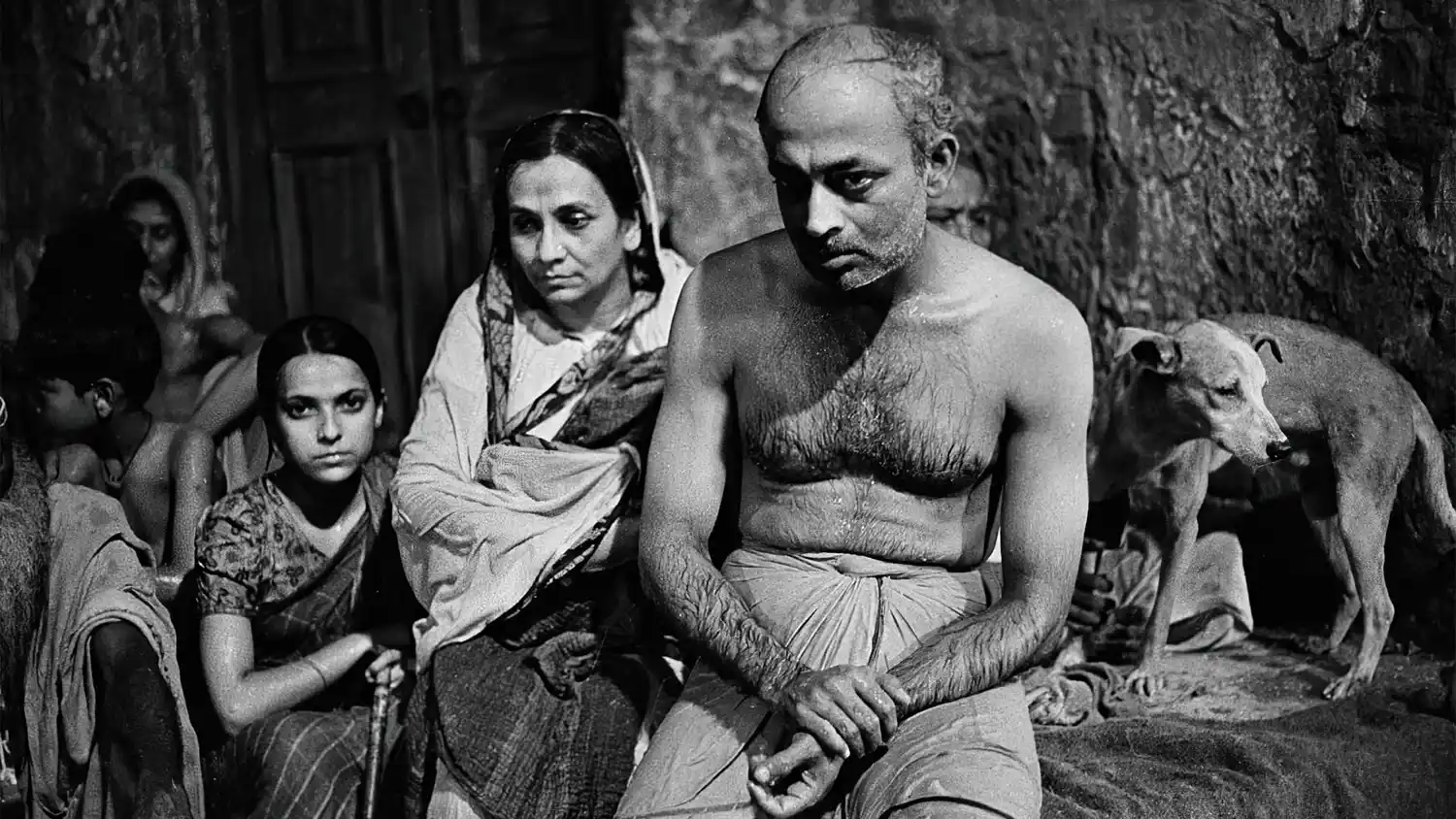

A Hindi period action drama starring Mithun Chakrabarty, “Mrigayaa” is based on a short story written by the Odia writer, Bhagbati Charan Panigrahi. Winning stupendously at the 24th National Film Awards, this film was remarkable for its background score by Salil Chowdhury. In the 1930s, the tribals and indigenous population suffered under the forest officials as well as the poachers. Sen combines this double bind with a miraculous agenda. A native tribal leader Ghinua joins hands with a British administrator who commands him to hunt a big game for an even larger sum.

It was at this point that an escapee revolutionary by the name of Sholpu arrives stealthily to meet his mother, only to find a policeman killed and the blame completely imposed on him. Sen completes the circle by showing a dichotomy, indulging in a red herring that none of us seems to have guessed. Sholpu’s murder was rewarded with pomp. On the other hand, when Ghinua murders his wife’s abductor, Sahib decides to hang him to death. Such a comedy of manners trombones a state-of-the-art turn for Sen, who explored this Shakespearean tale with finesse.

8. Kharij (1980)

Winner of the Golden Palm in the 1983 Cannes Film Festival, “Kharij” is a ‘murder’ story that astounds the advocates of ‘family first’ and kinships within consanguineal marriages. Also known as “The Case Is Closed,” this film is based on the 1974 novel written by Ramapada Chowdhury. The insensitivity towards a helpless child-servant Palan is the central theme of the story. Found dead in the kitchen mysteriously, the film revolves around the effort to come to a compromise with his father. Sen, in his mournful, lugubrious approach causes the plot to heed towards an assassination, only to divert the attention of the audience towards their own wrongdoings.

Spoiler: carbon monoxide poisoning from the burning coal oven would be fatal for anyone with prolonged exposure to it. Casting Anjan Dutt and Mamata Shankar, this bereaved and ageless trauma is beyond decadence. The ideal sequence of guilt, fright, and futile attempts to engross the police in their renderings complicates the matter further. Sen’s intensity and minimal use of background score lock the spectator inside a ticking clock that gradually turns into a specter. The question in “Kharij” surrounds us: “Who is responsible for the intermingled cataclysm of neglect, authority, and liability?” It is contemplative in its tonality with a painful pull of strings.

7. Chorus (1974)

Winner of the National Award for Best Feature Film in 1974, “Chorus” topped the chart as a satire of the ‘70s. With a star-studded cast featuring Utpal Dutt, Asit Bandyopadhyay, Gita Sen, Rabi Ghosh, and Haradhan Banerjee, Mirnal Sen went all-out in this revolutionary portrayal of the fearful throne of power. Chronicling the mindset of a Hirak Raja set in a distinct castle of expectations, it opens with a bard singing glory to the new Gods who have descended on the earth. The monochromatic world paves the way for an amusing yet disturbing standard in an Orwellian dystopia. The themes are not too far from the underemployed, malnourished, disconcerted world that we witness today.

However, at the time, Sen conveyed popular discontent in a manner few directors seldom attempted in popular Bengali Cinema. The role of the storyteller is fundamental to the upsurge of emotions and downplay of exclusivities in the film. It is the legacy of neo-realism that caught on with Sen and he juxtaposed documentary evidence and caricature with an emboldened demeanor. For instance, you offer a hundred jobs to keep revolt at bay, but a thousand cost-ridden faces queue up outside your house. The disturbance is ongoing as a photographer swiftly joins in to collect a ‘scoop’. The character of Mr. Mukherjee is the explicit face of the proletariat in the film who demands an increment in wages and a regular supply of essentials as and when needed. Overall, Sen’s sequencing and directorial judiciousness will put anyone in awe.

6. Calcutta 71 (1972)

“Calcutta 71” is still seen as one of Sen’s masterpieces in the Calcutta Trilogy, which was released between “Interview” (1971) and “Padatik” (1973). It is a case study in a cinematic nutshell, reacting once again to the famished Calcutta of 1971. Sen was vocal, critical, and outspoken. Unlike the humanism of Ray and the melodramatic leitmotifs of Ghatak, Sen was emerging with the honor of a migrant, a struggling yet ironic polemic voice that shook the audience. Inspired by the upfront stories of Manto, Sen indulged in the gory tragedies of the common people.

Demystifying the crux of cinema, “Calcutta 71” questions the blindness of realism. If attempted, it would triumphantly shatter the imminent institutions of formal compositions or the internationalist patronization of the Global South. Collecting raw footage for the film since 1966, Sen portrayed the counter-insurgency against the students and political leaders as well as the slogan of the Congress Party – ‘garibi hatao’ (‘Remove Poverty’). The influx of refugees, Maoist uprisings, and shortage of supplies infuriated the people after the Left had withdrawn from power. The state was slowly heading towards an inevitable Emergency in 1975 under the leadership of Indira Gandhi. Sen was ambivalent in his stance (between left-liberal and Maoist) but implicitly partisan. This film explores the terrain of political modernism by delving into the emotional juxtapositions among various segments of society.

Also Read: 101 Years of Mrinal Sen: Remembering the Icon of Indian Political Cinema

5. Akash Kusum (1965)

Influenced by Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” (1959), Sen was on the path to carve out his own version of romance. But, in his usual accent, Sen ended up making it a parallel film. Also known as “Up In The Clouds” (1965), this film also garnered immense controversy, with repeated ‘Letters to the Editor’ on its misinterpreted message. The film revolves around Ajay, a middle-class ambitious executive, who is shown to have apparently bluffed his lady-in-longing Manika, portrayed by Aparna Sen. Throughout the film, he is seen trying his hardest to dodge the consequences of his mediocre business decisions and failed dealings, ultimately leading to his massive downfall.

However, it was the film’s reception that stirred it abound. Ray called out its ‘modish narrative devices’ superfluous and criticized the hero’s conceivable topical point. Despite this, “Akash Kusum” grabs hold of a significant place in every Bengali spectator’s heart, owing to the youthful categorization of the split personality by Soumitra and the lively city scenes extensively shot on still frames. The class struggles that outpour amidst the yearning pulses of the lad make our experience closer to the several versions of truth as seen in the film.

4. Interview (1971)

Played by a young and energetic debut actor Ranjit Mallick, “Interview” will always be remembered as a tale of the rising generation. The hope is emblazoning and the colonial hangover is not yet over. Looking for a lucrative job, he is assured a position in a foreign firm by an acquaintance. The inherent flaws in the system are intelligible and lucid. Yet, Sen chose to showcase the friction as if fate played her cards. Ranjit’s Western-style formal suit was ordered to be taken well before the date of the interview, but a Union Strike flashes his future in seconds. His father’s suit would not fit him and the borrowed one was lost.

This anagnorisis is intermittently broken by the city’s splendor of colonial architecture and its bustling fish markets. The adverse effect of his failure would burst in an impressionable interview, a stance of outbursts, a rant against corruption, and an accidental lament against neo-colonialism. A delight with quick cuts and instances of pulp fashion magazines, Sen gives the audience a flashback of their own past.

3. Akaler Sandhane (1983)

Imagine a situation where you visit a poverty-stricken village to enact a play on famine, only to be submerged in the milieu of ‘inferiority’ that you were trying to avoid from the beginning! Such is the power of the ‘film-within-a-film’ technique that Sen opted for in the film, also known as “In Search Of Famine.” It is set in the year 1980, nearly 40 years after the human-made famine by Churchill destroyed the opulent condition of Bengali citizens. It is perhaps the only film where Sen participated as an actor, destroying the fourth wall and pushing the narrative in a robotic, almost sarcastic voiceover, in its essence.

While Smita Patil plays the protagonist, it is her encounter with Durga and the tantrums thrown by the actors on the set that rupture the confidence of the atmosphere. Interminably, the film tries breaking down the boundaries of the narrative set to trespass into the locale. It is without intention that the actors opt for method acting, failing miserably at their ‘realistic’ stance. Durga, playing the role of an impoverished mother, is in reality the same miserable woman who suffers the truth of the matter. In fact, she expresses her desire to throw away her child, simply because she cannot feed him. It is this undulating drama that fluctuates the magnetism of the actors. The awestruck villagers are as surprised by the sudden intrusion of the troupe as are the actors in their makeshift world of minute-long realities.

2. Padatik (1973)

It was a time ripe with the Naxalite Movement and Sen took over the artistic helm with splendor and vigor. Also called “The Guerilla Fighter,” this film featured Dhritiman Chatterjee as a runaway, underground political activist. Under the aegis of his leaders, he manages to escape the prison van and seeks shelter in the house of an affluent lady, played by Simi Garewal. The ideological pathway is brittle as bitter questions arise in direct contact with the upper class. Although Sen received considerable flak for his leniency towards both narratives, it is only through such a dilemma in political uptightness that he could effortlessly navigate the twisted narrative.

Shown in the Director’s Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival, Dhritiman’s effervescent denial of conviction and his intermittent dialogues with Prabhash Sarkar, a friend and his only remaining connection with the party, made the film a statement against the Marxist prowess. Sen had called it ‘stock-taking’, an effort at the technique of biographical auto-critique. Calcutta, being in an overturned state, was dejected by the haunted schemas of a North Korea-like state, as its party withheld the voice of the citizens. After the Moscow-Beijing split in the 1960s, party workers couldn’t reflect on the dogmatic steps of their own party. Hence, “Padatik” threw away the curtains of pseudo-liberation and proposed a renewed effort at leadership and veneration.

1. Bhuvam Shome (1969)

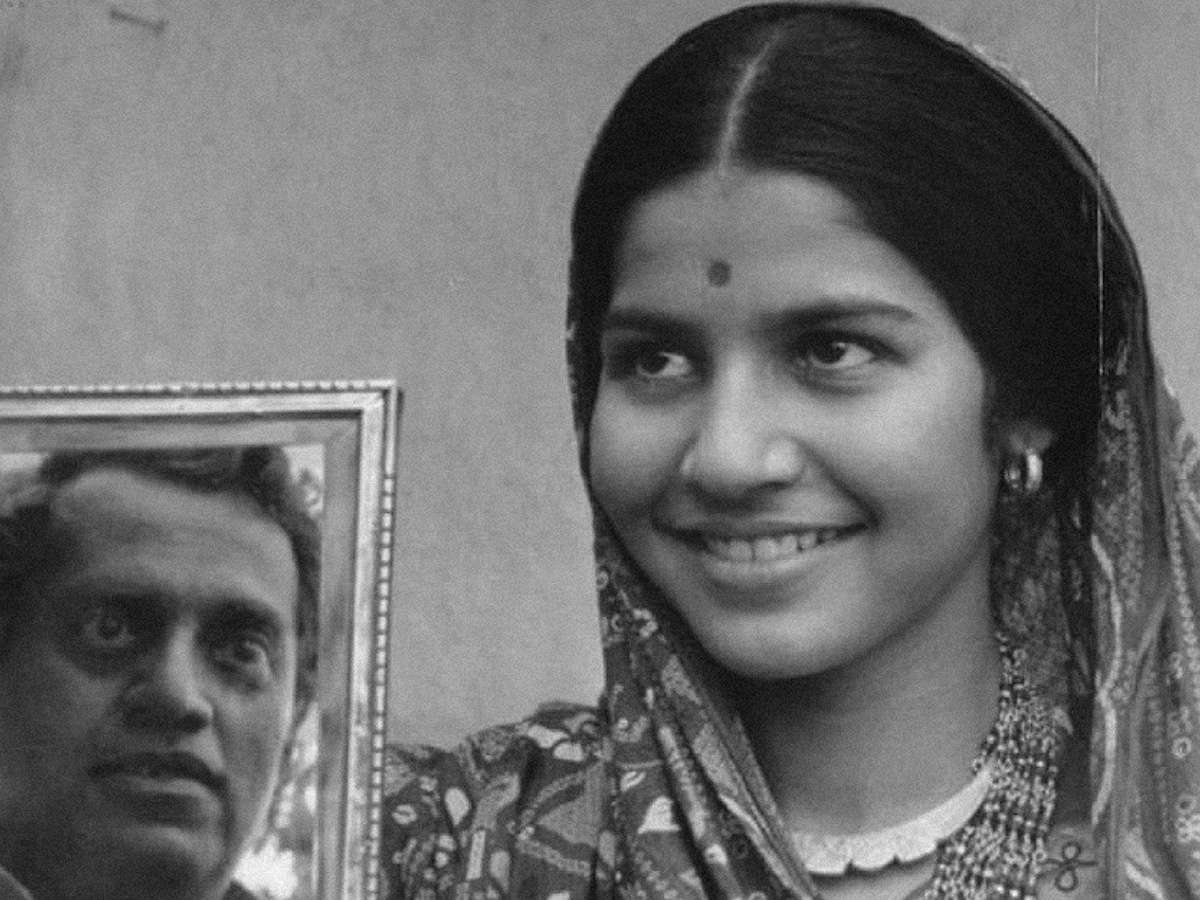

The Hindi drama “Mr. Shome” was a production that turned heads for stupendous feats. The village lass Gauri, played by the veteran theater actress Suhashini Mulay perfectly compliments the stubborn civil servant protagonist, Utpal Dutt. The film is known for the initiation of the New Wave Cinema in Indian film circuits, however, an even more covert reason lies in its sheer power of conviction. It centers around the story of Balai Chand Mukhopadhyay, revolving around the subtle Marxist analogy that Sen repeatedly showcased during the time of severe political unrest in the country at the time. It was a Bengali man’s hunting holiday in Gujarat that alter the trajectory of his life.

As an unequipped and incompetent ‘hunter’, the obverse comes alive when Gauri teaches him to hunt birds. The solitary life of the upright and virtuous widower is disrupted by a vibrant compassion that had long been absent from his world. The series of encounters between the two vividly illustrates how bureaucracy shrouds the heartfelt intimacy of camaraderie and companionship. The traditional rural-urban divide is repeatedly dismantled through Gauri’s innocent responses, her subtle mockery of success, and her quiet defiance of the prevailing social value system. “Bhuvam Shome” was also Amitabh Bachchan’s first narration in a film, breaking bounds for the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC), who agreed to produce this gem.