Film may well be the youngest of the seven arts, yet it has already shown itself to possess the greatest popular appeal – despite being a little over a century old, it commands increasing cultural influence across the globe. A good deal of this appeal certainly stems from the medium of cinema being fundamentally different from that of the other arts. For one, cinema presents itself as a singular patchwork (a montage even) of the other classical arts like music, literature, drama, and painting. Additionally, as Tarkovsky observed, cinema is sculpted in time – and this temporal dimension makes it the most dynamic as well as the most ephemeral of the art forms.

This multimodal structure of film allows for complex and comprehensive sensory experiences and brings us to a more immediate relationship with the worlds it presents for us. Paradoxically enough, it is precisely cinema’s close proximity to the real that explains its functioning as the realm of fantasies, as the manifest space where the churnings of human imagination are externalized and even ‘believed’ to the extent that viewers willingly suspend disbelief. From characters like Keaton’s projectionist walking ‘into’ a movie, or Norma Desmond losing herself within the glitter of celluloid to the real-life Hossein Sabzian ‘becoming’ Mohsen Makhmalbaf – cinema has routinely served to interrogate and confound sharp boundaries between reality and fiction.

It is this unique propensity within film to bring itself within its field of vision, to break the fourth wall, to address itself and make explicit its own construction, that has led to so many attempts across film history to represent and reflect upon the phenomenon of cinema itself. In this article, we explore a diverse range of such attempts across 30 great films about films, instances when cinema mirrored itself – encountering everything between the poles of fiction and documentary, and even going beyond such constructs and into uncharted terrain, where film exposes the dialectic of fact and fabrication propping up its reality, as fragile and fleeting as the celluloid image itself. Enjoy.

“Film is truth 24 times a second, and every cut is a lie” – Jean-Luc Godard

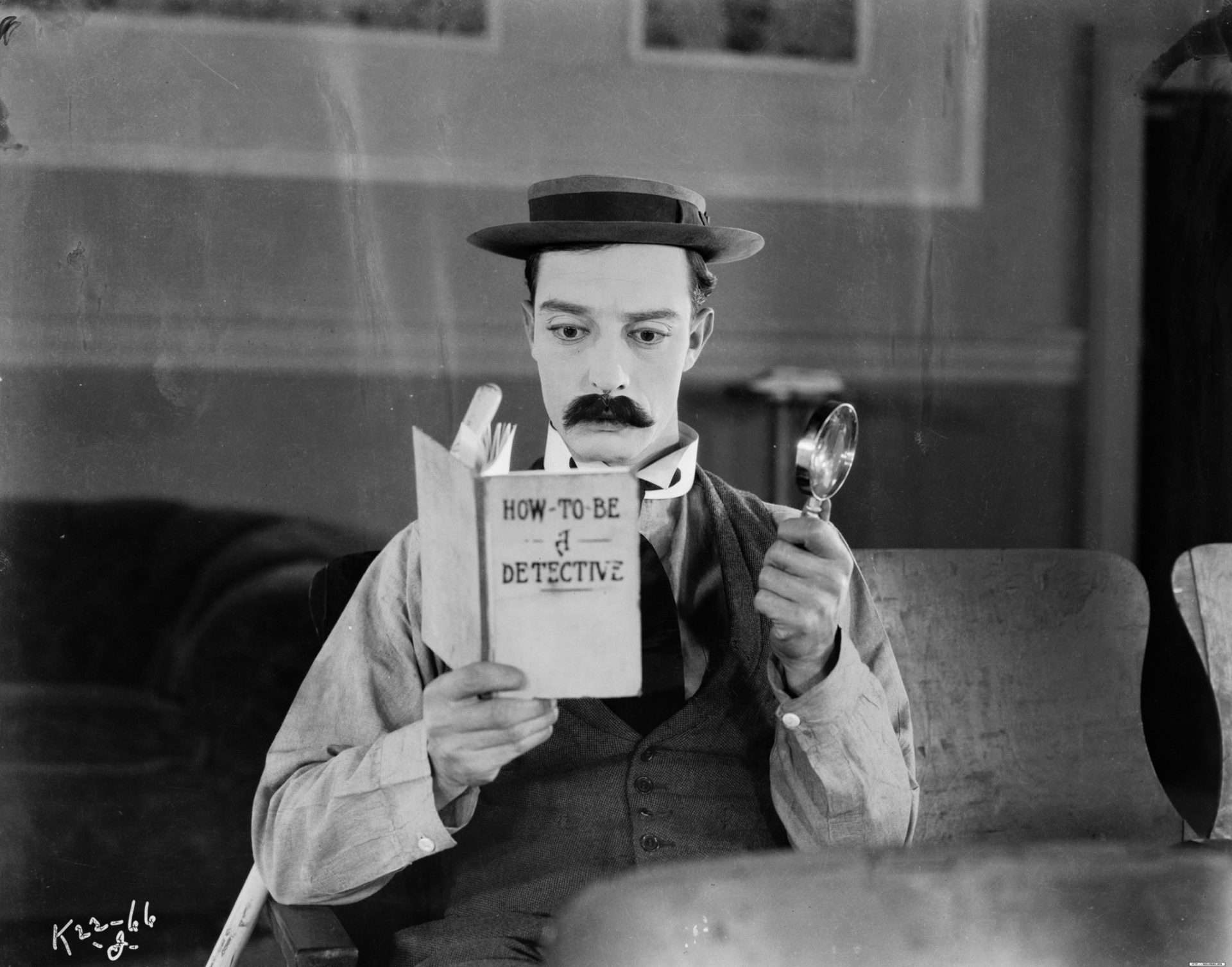

1. Sherlock Jr. (1924)

One of the earliest movies to utilize the ‘film within a film’ narrative design, this silent classic by the master of physical comedy Buster Keaton deftly highlights the fantasy realm inherent within the cinematic medium. Keaton’s character works at a movie theater as the projectionist and janitor and reads a “How to Be a Detective” book when the cinema isn’t running. He has a rival referred to as “The Local Sheik,” against whom he must compete for the affection of the woman he’s drawn to. Nearly broke, the two of them try outdoing each other in their attempts to buy chocolates for the lady, with the sheik stealing her dad’s pocket watch and pinning the blame on Keaton’s projectionist. Following a series of shenanigans where the projectionist attempts to one-up the sheik, we see him dozing off at his job during the screening of a movie about a necklace theft.

Here, the film shifts gears, moving into a dreamscape where the sleeping projectionist enters the movie and takes on the role of “the world’s greatest detective,” Sherlock Jr., as other people from his life substitute for the side characters. Keaton later admitted that this singular moment depicting his character walking into the filmic narrative, from reality to cinema, was “the reason for making the whole picture… Just that one situation.” By identifying the cinematic apparatus with dreams, Sherlock Jr. hints at how the movies provide us with a moment of respite from the pressures of waking life, allowing us to project our repressed wishes and fantasies onto the silver screen. It was also one of Buster Keaton’s most technically complex productions, featuring innovative optical effects and camera tricks (such as Keaton’s character going inside a suitcase and disappearing) that foreground the storytelling capabilities unique to cinema.

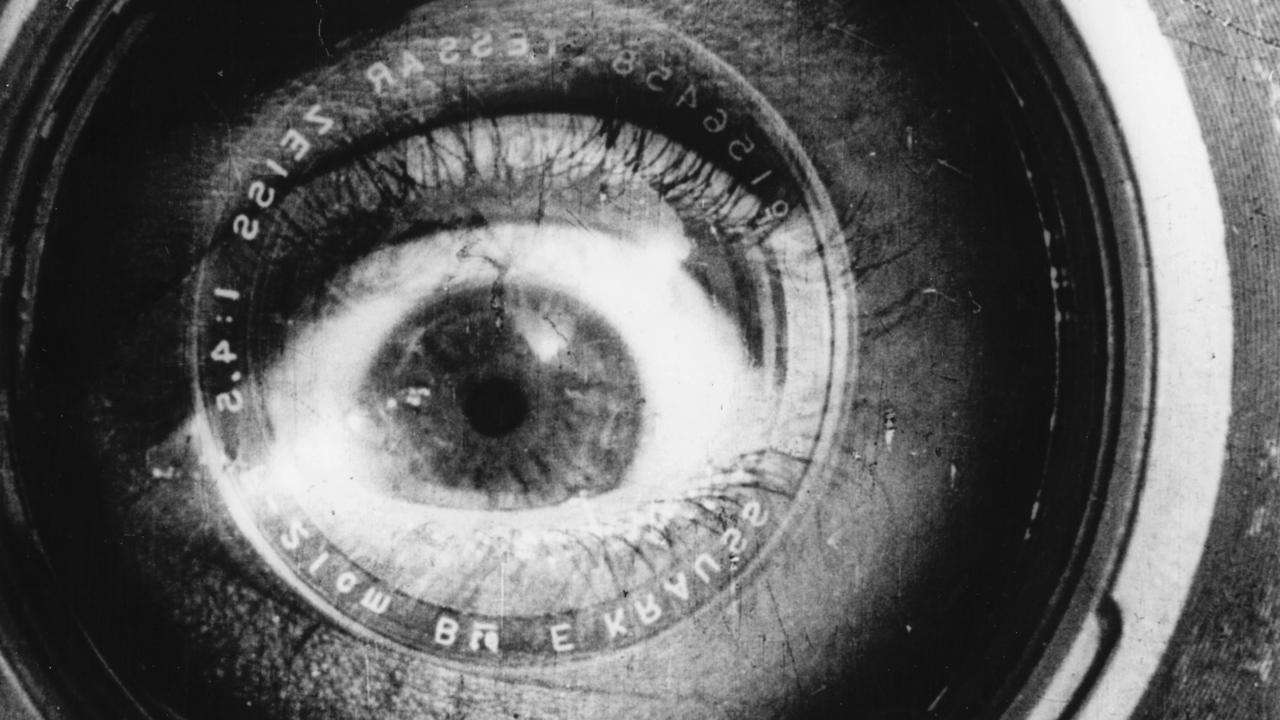

2. Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

Very few works in the history of cinema have taken the medium’s artifice as seriously as Dziga Vertov’s silent documentary Man with a Movie Camera, counterposing it against the camera’s penchant for realism to explicate the fundamental elements of cinematographic art. It opens with a meta-reflexive shot of the eponymous “Man” (played by Vertov’s brother Mikhail Kaufman) assembling his “Movie Camera” before proceeding to film the residents of Odessa waking up, with people going about their daily chores in a bustling urban environment. The ambition, in general, was to capture a city in motion and document the industrial and lifestyle changes brought about by modern technological progress. From scenes of birth and death to factory workers and sporting events, the movie camera captures a panoramic view of Soviet life in the late 20s.

Vertov’s motivations for making the film are spelled out at the outset through title cards as “the creation of an authentically international absolute language of cinema based on its complete separation from the language of theatre and literature.” He was part of the avant-garde filmmaking group Kino-Eye, which sought to transcend the boundaries of fiction film by emphasizing the documentary potential of the camera. Interestingly, Vertov displays acute self-awareness of his film’s construction by representing the process of filmmaking that went into its production. Largely dismissed upon its initial release by critics and audiences alike, Man with a Movie Camera proved to be way ahead of its time and is now popularly considered one of the greatest feats of experimental filmmaking ever.

3. Sunset Boulevard (1950)

While Vertov’s film emphasized cinema’s ability to touch the real, Billy Wilder’s classic Sunset Boulevard highlights the accompanying suspension of disbelief that lends veracity to cinematic constructions – always threatening to disintegrate into the outright psychotic disavowal of reality. Starring William Holden as the struggling Hollywood screenwriter Joe Gillis, the film opens with the police and paparazzi discovering his dead body in a swimming pool and narrates in flashback the events leading up to it. Six months prior, we see Joe encountering the now-forgotten silent film star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in her deserted mansion. Norma is planning a return to the silver screen with a film she’s written herself, and Joe agrees to be her script doctor despite hating the script – the first of several fabrications propping up the façade of reality in the narrative.

After moving into Norma’s mansion to work together, Joe gradually discovers the degrees of denial structuring her reality – Norma cannot accept the fact that her star has faded, and her delusions are buttressed by the fan mail she keeps receiving, the letters being secretly written by her butler Max (Erich Von Stroheim). Things get more complicated as Norma falls in love with Joe and slashes her wrists when the latter doesn’t reciprocate her feelings. She sends her script to her old director Cecil B. DeMille (playing himself) at Paramount and starts getting calls from their executives, leading her to fantasize about her imminent Hollywood return when they are only interested in renting her car – an unusual luxury model – to use in some movie shoot. With layers upon layers of illusion pushing any truth firmly out of sight, the film’s unforgettable climax finds Norma’s faculties for disbelief completely suspended, the boundaries between the reel and the real dissolving completely as the screen fades to black.

4. Singin’ in the Rain (1952)

Widely regarded as one of the greatest musicals ever made, Singin’ in the Rain is set in late 20s Hollywood and tells the story of the difficult transition from the silent era to that of the talkies. Gene Kelly, who co-directed the film alongside Stanley Donen, plays the silent film star Don Lockwood, linked romantically to co-star Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen) by their producers to publicize their latest offering, The Royal Rascal. Don tolerates Lina with much difficulty and instead has his eyes on theater actress Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), who also happens to be an admirer of Don. Meanwhile, their boss, R.F. Simpson (Millard Mitchell), unsuccessfully tries impressing his guests with a demo of the sound film, the latter convinced that this new development shows no promise. However, following Warner Bros’ release of their first sound production, The Jazz Singer (1927), to enormous commercial success, R.F. decides that their next film starring Don and Lina, The Dueling Cavalier, will be a talkie.

Unfortunately, the film’s preview screening is beset with technical issues, and Don’s best friend, Cosmo Brown (Donald O’Connor), suggests turning it into a musical and dubbing Lina’s voice with Kathy’s to save it. The Dueling Cavalier becomes The Dancing Cavalier, much to Lina’s chagrin, as she threatens to sue R.F. unless he keeps Kathy’s involvement strictly under wraps. Lina thus represents the fading silent film star, as her lips move without producing sound, while Kathy stands in for the sound era, filling in Lina’s silence with her singing. This paves the way for a wittily orchestrated ending where Lina’s ruse is exposed, and Kathy is branded “the real star” by Don – a nod to the triumph of the sound film over the silent era, despite all the naysayers.

5. The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)

While Singin’ in the Rain was a celebration of Hollywood’s great success, released in the same year, Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful dramatizes the ugliness inherent within all that silver screen glitter. It tells the story of Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas), the son of a much-loathed ex-studio head, who has a new idea for a film but needs help financing it. However, the three people he contacts – his past collaborators Fred Amiel (Barry Sullivan), Georgia Lorrison (Lana Turner), and James Lee Bartlow (Dick Powell) – refuse to speak to him. Through a series of flashbacks, the stories of their involvement with Shields are revealed. In each case, the person concerned is ultimately betrayed by Shields, following an initial period where the two worked together for mutual benefit.

Curiously, however, the betrayed party in each case also went on to attain great career success, derived seemingly from the consequences of Shields’ betrayal itself: Amiel becoming an Oscar-winning director, Lorrison a top Hollywood star, and Bartlow winning the Pulitzer Prize. In the present, film producer Harry Pebbel (Walter Pidgeon) tries to convince them to work with Shields one more time despite their past betrayals, which, he observes ironically, nevertheless led to their present glory. With complex characters based on several real-life American movie legends, The Bad and the Beautiful portrays the paradoxical world of moviemaking, where self-interest and egotism often become the engines driving creative output. The film went on to win five Academy Awards and remains one of the best examples of Hollywood taking a hard look at itself and reflecting on the toxic ethos that often underlies the most dazzling works of art.

6. 8½ (1963)

8½ is a film where there seems to be no single central conflict except the one lying in its genesis: the possibility of such an impossible film getting made. It opens with a dreamlike sequence of a man suffocating and one flying too high before getting unceremoniously pulled down to earth. As deliberate references to Fellini’s creative crises following his last film, La Dolce Vita‘s international success, these images convey the stakes involved in the making of his latest project, carving out the creative hole he finds himself in. His predicament is shared by the film’s protagonist, Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), a famous Italian film director who finds himself stuck in a rut as he struggles to finish his latest project, confronting the impossibility of pleasing everyone. 8½ is a brazen document of an artist coming to terms with his creative urges and his commitment towards truth – his truth – and his utter inability to bridge the deep chasm between real and reel life. Guido’s artistic commitment to a deeper truth conflicts with a world where ‘truth’ is only recognized as such in neat and ordered packages.

In Fellini’s hands, as channeled by his stand-in Guido, cinema transcends its anchorage in material reality and becomes a carnival of abstract entities like dreams, memories, hopes, desires, frustrations, and failed pursuits. With the character of the film critic Daumier (Jean Rougeul), hired by Guido to help with his production, the film manages to critique itself and contain the laughter and contempt that Fellini directs at his naively idealistic self, tortured by the desire to attain the ever-elusive ideal of a masterpiece. In the end, Guido finally lets go of his lofty ambitions of reconciling personal anxieties through his creative work and embraces his bit part in the absurdist circus that is life. Through his stand-in Guido Anselmi’s royal failure to realize his magnum opus, Fellini thus paradoxically realizes his own, both men attaining the revelation that the truth of life (and art) cannot help but remain confounding and absurd.

7. Contempt (1963)

Cinema’s enfant terrible Jean-Luc Godard made his first and last venture into big-budget star-studded filmmaking with his 1963 picture Contempt, based on the Italian novelist Alberto Moravia’s Il Disprezzo (A Ghost at Noon). Featuring the likes of Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance, and legendary German filmmaker Fritz Lang (playing himself), Contempt is shot in color Cinemascope and reflects a lot of Godard’s personal frustrations with the moviemaking industry. The story revolves around a screen adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey, to be directed by Lang and produced by the obnoxious American Jeremy Prokosch (Palance). The two of them disagree over how to interpret the source material: Lang wants to make an art film, while Prokosch is more interested in commercial success. Prokosch hires Paul Javal (Piccoli), a young French playwright, to help rewrite the script. Paul arrives on set with his wife Camille (Bardot), a former typist, the latter being hit on by the crude Prokosch.

However, when Paul seems unperturbed by the producer’s sexual advances towards his wife, Camille begins to suspect his fidelity – wondering if she’s being used by Paul to secure his foothold with Prokosch. Her suspicions are soon confirmed, and Camille’s love turns to contempt, with the ensuing marital rift complicating the issues already plaguing Prokosch’s production. Contempt is notable for its production also being rife with problems, with Godard frequently clashing with his producers who were upset at the absence of erotic scenes featuring the sex symbol Bardot. “Hadn’t they ever bothered to see a Godard film?” he had remarked. Nevertheless, Godard obliged them in his singular ironic fashion with an unforgettable prologue showing Camille in bed, explicitly addressing each part of her nude body as Paul monotonously reassures her of his love. “Acres of skin but no eroticism,” as Roger Ebert described it.

8. Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968)

A layered cinematic experiment like none other, William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One can be described most accurately with the following head-spinning formulation: it is a documentary of a documentary of a documentary. In 1968, at a time when America was grappling with protests over the Vietnam War and a rising countercultural movement, Greaves assembled in Central Park, NYC, with a set of actors and three camera crews to realize his unconventional idea for a film. The pretense involved the actors auditioning to Greaves for a documentary he called Over the Cliff, with Greaves instructing the first film crew to simply document this audition process. In turn, however, he tells a second film crew to document the first one (already documenting the actors) and instructs the third team to film anything relevant to the project’s overarching theme (“sexuality,” according to Greaves), including the first two camera setups, the actors, and Greaves himself (who also happens to be wielding a camera).

To complicate matters, Greaves seems to appear in his own “documentary” as a character – playing an unprofessional, confused, and even sexist director – instead of being his regular himself, confounding any easy demarcation of reality from fiction. His erratic behavior sows discord among his film crews, who plan a mutiny, all this drama making it into the final cut due to the constant presence of cameras. Aside from raising questions about how photographic realism and cinematic suspension of disbelief constrain and undermine each other, the movie stages a battle between the ideologies dominating the film scene of its time. On the one hand, there’s the auteur-director Greaves, representing the concentration of power within the individual (per auteur theory’s ideals of creative autonomy), and on the other are his disjointed film crews, representing the antagonism of the collective. Thanks to its bizarre form and experimental content, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One failed to secure distribution for decades until Steve Buscemi and Steven Soderbergh recognized its potential and helped Greaves finally release his work in 2006.

9. Day for Night (1973)

A decade after Godard’s cynical take on the moviemaking industry in Contempt (1963), fellow French New Wave pioneer François Truffaut made Day for Night with starkly different ambitions – in his words, “to show why it is good to love the cinema.” The film stars Truffaut himself as the film director Ferrand, working on a melodrama whose production encounters several hitches along the way. As Ferrand navigates the endless series of challenges thrown up by a film set, we see his film crew getting caught up in various romantic affairs, only adding to the complications. The title Day for Night refers to the Hollywood studio technique of filming night scenes in broad daylight, either with a lens filter or specially treated film stock.

One of the film’s primary preoccupations is the enormous amount of make-believe that goes into making a film seem “realistic,” such as the shooting style referred to in the title, deriving from the techniques of artifice popularized by Classical Hollywood cinema, of which Truffaut was an avowed fan. His film is thus fittingly dedicated to the early American silent film actresses Lillian and Dorothy Gish, known for appearing in the films of D.W. Griffith – who himself pioneered numerous cinematic devices. Notably, Godard was outraged upon seeing Day for Night, calling it a dishonest representation of filmmaking in a series of letters to Truffaut, which decisively ended their already-straining friendship. The film also won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1974 and is widely considered to be one of Truffaut’s finest works.

10. The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

The year is 1940 in Spain, shortly following the end of the Spanish Civil War when the dictator Francisco Franco came to power. Six-year-old Ana (Ana Torrent) lives in a small hamlet with her elder sister Isabel (Isabel Telleria), her daydreaming mother Teresa (Teresa Gimpera), and her father Fernando (Fernando Fernán Gómez), who meticulously tends to and writes about beehives. One day, a traveling cinema screens the 1931 movie Frankenstein in their village, which profoundly affects young Ana. In the movie, Frankenstein’s monster is seen playing with a little girl and then accidentally killing her, and then himself getting killed by the villagers, which leaves Ana disturbed and questioning the deaths. Isabel reassures her by insisting that the girl and the monster aren’t really dead and that “Everything in the movies is fake.” Nothing we see on-screen is real, but rather, they stand in for a reality that can only be expressed via mediation. With this pithy observation articulated between two children, director Victor Erice reminds his viewers of the central representative function of movies.

The point is all the more significant for The Spirit of the Beehive, replete with subtle symbolism alluding to Spanish life under the Francoist regime. It is precisely by leveraging this aspect of “fakeness” of cinematic representation, and thus mounting his socio-political critique through veiled and indirect means, that Erice managed to bypass Franco’s censors. This blurring of boundaries between concrete reality and imagined fantasy is a feature not just of the cinema but, as the film shows, also of childish imagination – whose power we witness when, in a nearby sheepfold, Ana meets a wounded Republican soldier (Juan Margallo), hiding from Francoist police. Thinking that the monster from Frankenstein didn’t really die, Ana’s imaginary faculties identify his undead spirit with the soldier in front of her, and she strikes up an unlikely friendship that brings to mind the events of the movie she’s obsessed with.

Read More: 10 Great European Movies That You Just Can’t Miss

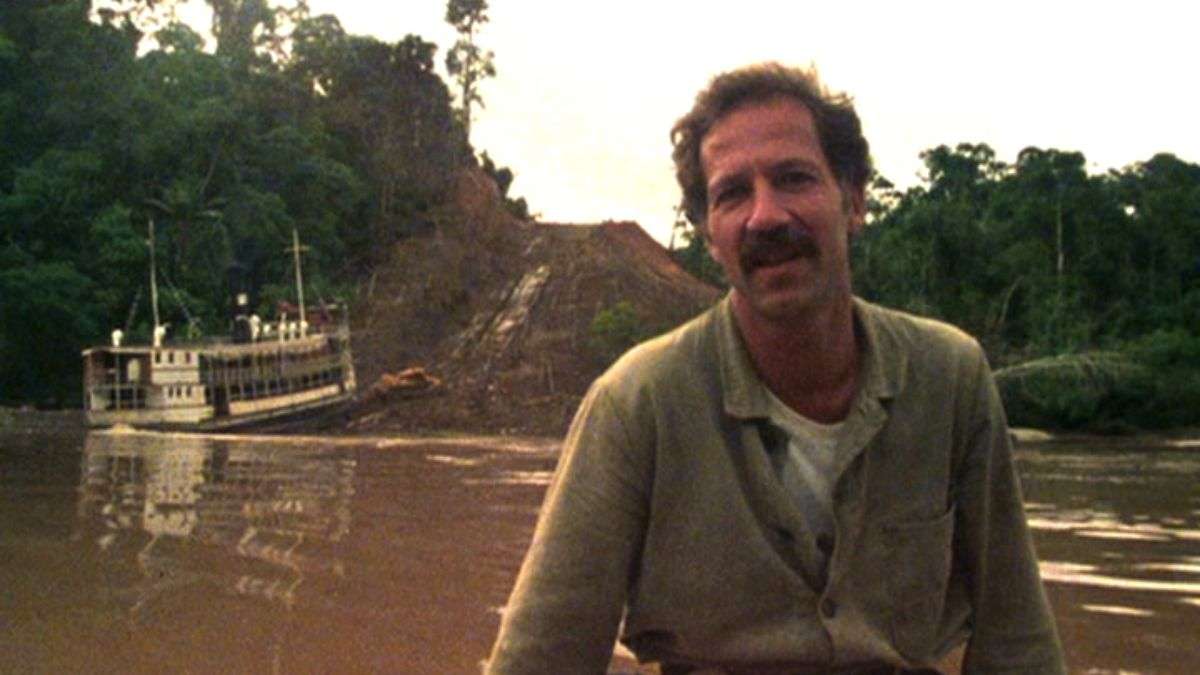

11. Burden of Dreams (1982)

In January 1981, the inimitable Werner Herzog assembled in the Amazonian rainforests of Peru with his cast and crew to attempt the near-impossible: filming his masterpiece project Fitzcarraldo (1982) entirely through on-location shooting. What ensued was one of the most infamous cases of development hell in cinematic history: people fell sick, some died, a border war broke out between local Indian tribes, a plane crashed, and more. The leading actor, Jason Robards, caught dysentery and went back midway into the production, with Klaus Kinski replacing him. Les Blank’s documentary Burden of Dreams captures all the pandemonium that went on behind the scenes of filming Fitzcarraldo and presents a monumental testament to the extremes that impassioned filmmaking can go to.

The story of Fitzcarraldo involves the protagonist hauling a massive steamship up a steep hill, and the documentary shows Herzog attempting to pull it off entirely manually, without special effects. Herzog had to shift the whole production some twelve hundred miles when the initial location was overrun by the local Indians. We see how the stress of finishing the project drives the filmmaker delirious, a situation only complicated by his clashes with his leading man, Kinski. Herzog is seen remarking, “If I abandon this project, I would be a man without dreams, and I don’t want to live like that.” This is what forms the main subject matter of Les Blank’s documentary: the overwhelming burden of the dreams driving Herzog to unimaginable lengths, coupled with the burgeoning guilt of people around him suffering and dying just to see his vision realized.

12. Cinema Paradiso (1988)

The film that revitalized Italian cinema in the late 80s, Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso, remains one of the greatest celebrations of cinema’s magic to this day. Structured as a coming-of-age tale, the events are narrated in retrospect as the protagonist, Salvatore Di Vita (Jacques Perrin), a renowned film director in Rome, learns that his childhood friend and mentor Alfredo (Philippe Noiret) has died. He recalls his childhood spent in the Giancaldo village in Sicily, which he hasn’t visited in three decades. The young Salvatore, nicknamed Toto (Salvatore Cascio), is an eight-year-old movie buff who rushes to the local movie hall Cinema Paradiso every chance he gets. It is there that he strikes up a deep friendship with the projectionist, the middle-aged Alfredo.

Alfredo teaches Toto how to operate the projector and also acts as the censor of his screenings– splicing out “juicy” bits from the film strips as ordered by the local priest who owns the place. One day, the movie house catches fire, and Alfredo is left blind when a reel explodes in his face. After one of the patrons helps rebuild the cinema, the young Toto must become the new projectionist since he’s the only one in the village who can operate the machine. Immersing himself wholly into the world of cinema, Salvatore begins experimenting with the camera and films a girl named Elena (Agnese Nano) with whom he’s fallen in love. Cinema Paradiso won the Grand Prix award at Cannes and the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

13. Close-Up (1990)

A masterful docufiction from Abbas Kiarostami, Close-Up blurs the boundaries between fiction and reality like none other, fundamentally rethinking the creative potential of the documentary format. It retells a real-life incident that took place in late 80s Tehran, where a man named Hossain Sabzian impersonated the famous Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, whose films he admired. We see Sabzian, a devout cinephile, riding the bus with a copy of the screenplay of Makhmalbaf’s 1987 film The Cyclist. When a woman, Mrs Ahankhah, sits next to him and declares her love for the film, Sabzian claims to be Makhmalbaf himself. Learning from Mrs. Ahankhah that her sons are interested in the cinema, Sabzian visits them several times with promises to cast them in the film he’s making, but he’s eventually caught and tried for attempted fraud.

Kiarostami managed to get all the real people involved in the incident to play themselves, recreating the original farce in front of his camera. He also filmed the original trial, where Sabzian meets the real Makhmalbaf and is offered a ride home by his hero. Through this incredible narrative that demolishes conventional real/fake binaries, Close-Up reflects on cinema’s singular capacity for capturing reality through mimesis – a unique feature of the medium that allows it to ‘touch’ the real, but only, as it were, from a distance necessitated by cinematographic representation. Kiarostami’s film, after all, is just as much of a ‘fake’ as Sabzian himself was – both at a distance from the reality they strive to replicate and both inviting our willing suspension of disbelief, much like cinema itself.

14. Barton Fink (1991)

Another movie that explores the deceptive and fabricated nature of the filmmaking business (among other things), Barton Fink is one unconventional masterpiece from the Coen brothers that went on to win the top 3 prizes at Cannes. The eponymous Barton Fink (John Turturro) is a Broadway playwright in early 40s Hollywood who accepts a commission to write a commercial wrestling movie script from the vulgar producer Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner) at Capitol Pictures. Unfamiliar with his new milieu and the subject of his script, Fink is stuck and unable to make progress. He is disturbed by the noise coming from the adjacent room in the cheap hotel he’s staying at and soon meets the occupant, Charlie Meadows (John Goodman), who describes himself as an insurance salesman.

However, all hell breaks loose for Fink after his desperate plea for help from ghostwriter Audrey Taylor (Judy Davis) turns into them having sex, and Fink wakes up the next morning to find Audrey murdered in his room. His new friend Charlie helps him clean up but forbids him to contact the police. Charlie leaves for New York soon after, leaving a package behind for Fink – who is informed by a couple of police officers that Charlie is actually a serial killer named Karl Mundt who beheads his victims. All of a sudden, as if jolted by these revelations and the enigmatic box left by Mundt, Fink starts writing feverishly and finishes his script. Funnily enough (and perhaps not coincidentally), Joel and Ethan Coen came up with the idea for Barton Fink just as they were similarly suffering from writer’s block in the middle of preparing the script for their 1990 film Miller’s Crossing.

15. Through the Olive Trees (1994)

The third entry in Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy, Through the Olive Trees, takes the viewer behind the scenes of the filming of its predecessor, And Life Goes On… (1992). In a classic case of cinema intruding upon reality, the lead actor Hossein Rezai – a local stonemason – falls for and proposes marriage to the lead actress Tahereh, a student orphaned by the recent earthquake (whose consequences are the subject of Kiarostami’s previous film). Tahereh’s family disapproves of a match with a poor, illiterate man, and thus she keeps avoiding him, even while they are filming as lovers (thus reversing the logic as real life intrudes upon cinema). However, Hossein is determined to woo her, and the tension between them complicates the production, with the director (Mohamad Ali Keshavarz) stepping in to advise him.

The famous final scene of the film shows in a long shot Hossein finally getting an answer from Tahereh, but the viewer doesn’t get to know what she says given the camera’s distance from them. Hossein is seen running back to the olive groves through the lush green fields, and the film ends without disclosing its principal secret. Through this so-near-yet-so-far narrative device, Kiarostami reminds us once again that the cinema can only get so close to reality, with some residual distance from the real always remaining unbridgeable. Each film in his Koker trilogy becomes a meta-reflective examination that brings out the fictionality of its predecessor, and Through the Olive Trees goes the greatest distance in representing the process of filmic representation itself. As aptly noted by Godfrey Cheshire: “Rather than considering cinema as a mirror held up to life, it contemplates both life and the mirror, as well as the relationship between them.”

16. Salaam Cinema (1995)

Life and cinema are virtually indistinguishable within Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s films, and perhaps the most striking instance of this symbiotic relationship can be found in Salaam Cinema, a visionary love letter to the medium on its 100th birth anniversary. Appearing as himself, Makhmalbaf has put out a casting call for his next movie and is immediately staggered by the humongous response he receives. Thousands of men and women have turned up, all clamoring to get a role, and they’ll try anything and everything to be a part of the film industry. The very first applicant, for example, a young man pretending to be blind, spins the lie that he can feel cinema much more intimately despite (or, perhaps because of) his lack of eyesight. But Makhmalbaf is a strict taskmaster and not much escapes his keen scrutiny of the screen tests, as he repeatedly challenges, criticizes, and confuses the applicants to tear down any façade they dare put up.

He insists that the applicants laugh and cry instantly on command, which, although a little too much to expect from non-professionals, really is just a test of how far these people are willing to push themselves and fuse their interior selves with their on-screen personas. Like his contemporaries in the Iranian New Wave, Makhmalbaf is primarily interested in filming the ‘real’: real humans, real emotions, real drama, and real outcomes, and so these people are his film’s subjects as much as they are his actors. The astute drivenness with which Salaam Cinema achieves this simultaneous tribute, portrayal, and post-mortem of modern Iranian cinema makes it an unexpectedly tense and thrilling experience. “If the cinema reflects on life, then there’s room for everyone.”

17. The Mirror (1997)

The film that won Jafar Panahi the Golden Leopard at Locarno, cementing his status as an auteur of international repute, The Mirror is a masterful genre-bender that represents, in a nutshell, the key meta-reflective ambitions of Iranian New Wave cinema. We see a first-grader called Mina (Mina Mohammad Khani) making her way home across the bustling, chaotic streets of Tehran all by herself when her mother abruptly fails to pick her up from school. Dressed in her school uniform and with one hand in a cast, the determined little girl solicits the help of the strangers she meets, not all of them equally helpful. The camera, meanwhile, observes little Mina navigating the city on her own while maintaining a fly-on-the-wall distance. And then, the sacred fourth wall (functioning more like a mirror) shatters all of a sudden as Mina looks straight into the camera and announces that she’s tired of her role and quitting, even as Panahi’s voice off-screen tells her to look away.

Mina stops “acting” but the film doesn’t stop, and the camera now keeps following the film crew as they try and persuade Mina to change her mind. What seemed initially like a documentary is suddenly revealed to be fabricated, but as soon as this revelation is incorporated into the narrative, it seemingly becomes a documentary again. But when the camera reveals itself to be such an unreliable narrator, it becomes impossible to separate fact from fabrication with any certainty, and one might well suspect the whole thing to be an elaborate charade. Reality and fiction seem to differ only by degrees of the viewer’s will to suspend disbelief. And what does this mean for the old question regarding cinema’s potential for holding a mirror to our realities?

18. American Movie (1999)

Chris Smith’s American Movie is a cult classic documenting the life of independent filmmaker Mark Borchardt as he struggles to produce his horror short Coven (1997). Borchardt, in his 30s, leads a pitiful life, living with his parents, working two jobs to keep poverty at bay, battling alcoholism, and nursing threats from his ex-girlfriend because he’s behind on alimony. Far from the picture-perfect image of success, Borchardt is nevertheless obstinately passionate about filmmaking and determined to find success in cinema, and it’s the story of his sheer willpower that’s the subject of American Movie. His lifelong dream has been to make an epic feature he calls Northwestern, which he cannot produce on his own, hence the attempt to make Coven to help raise funds.

Alternating between being achingly sad to screwball comedy-levels funny, American Movie captures the incredibly messy process of amateur filmmaking – lacking resources but more than made up by sheer love for the craft (recalling the roots of the word ‘amateur,’ which comes from the Latin ‘amator’ meaning ‘lover’). We see Borchardt’s knowledge of filmmaking constantly being undermined by his failure at planning things out, as he recruits friends and clueless local actors to finish his film, even discharging cinematography duties to his mother. He also talks about his favorite films, like Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), begs his senile Uncle Bill, who lives in a trailer, for additional funds and occasionally ruminates pensively about his own life. A passionate love letter to the spirit of independent cinema, American Movie is a must-see for all aspiring filmmakers.

19. Mulholland Drive (2001)

From the iconoclastic master of the surreal David Lynch comes this twisted tale set in Hollywood, a film that has generated countless hermeneutic exercises trying to unravel its meaning. It opens with an unnamed dark-haired woman (Laura Harring) surviving an attempted murder car crash on Mulholland Drive, thanks to a few drag racers around. In a daze, the woman escapes and takes shelter inside the apartment of an old-time actress going away on vacation. She’s greeted the next morning by the aspiring actress Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), the latter shocked to see this stranger inside her aunt’s home. The woman seems to have lost her memory and calls herself Rita, a name she makes up after spotting a poster of Rita Hayworth inside the apartment. Together, the two women try to uncover Rita’s real identity using various clues, such as the contents of her purse: a strange blue key and a pile of money.

But this attempt at unraveling Rita’s mystery, which never really gets solved, takes them (and the viewer) down a dark and winding path strewn with curious oddball characters and unexpected dead ends and U-turns. As the film progresses, it gets increasingly impossible to separate objective fact from the realm of imagination and dreams (or nightmares, to be more specific), the topsy-turvy narrative becoming a heady cocktail of mistaken/swapped identities, mysterious puzzle boxes, mobsters, and terrifying hallucinations. Lynch initially planned Mulholland Drive as the pilot episode of a potential TV series, which never got greenlit and forced him to turn it into a feature film instead. He has staunchly refused to provide any explanations as to its confounding narrative, describing it only as “A love story in the city of dreams.”

20. Adaptation (2002)

From the master of metafiction, Charlie Kaufman comes this film about Charlie Kaufman struggling with writer’s block while adapting Susan Orlean’s book The Orchid Thief (1998). Directed by Spike Jonze, Adaptation is as funny as it is boldly inventive in depicting the travails of screenwriting through Kaufman’s eyes. When Columbia Pictures hires the self-loathing and socially anxious Charlie Kaufman (Nicolas Cage) to adapt The Orchid Thief for the screen, he desires to go beyond industry formulas and find a way to be more faithful to his source material. But his elevated ambitions aren’t matched by what he makes of Orlean’s book, and he’s stuck with the project. Having already transgressed Columbia’s deadline, Charlie decides to visit New York City and discuss his script with Orlean (Meryl Streep) herself.

To complicate matters, his twin brother Donald (also played by Nicolas Cage) has moved into Charlie’s house and is living off him. Donald, however, attends seminars by screenwriting expert Robert McKee (Brian Cox) and comes up with a screenplay pitch that is selling for millions. A desperate Charlie asks his brother to help him, and Donald ends up interviewing Orlean in Charlie’s stead. Triggered by some of Orlean’s responses, the Kaufman brothers follow her to Florida to catch her rendezvous with John Laroche (Chris Cooper), the protagonist of The Orchid Thief and Orlean’s secret lover. The craziness of what ensues, filled with much violence followed by sparks of hope, results at least in Charlie Kaufman finishing his script. As Roger Ebert has rightly noted, “To watch the film is to be actively involved in the challenge of its creation.”

Read More: 10 Best Nicolas Cage Movie Performances

21. Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)

An old and decrepit movie theatre in Taipei is on the verge of closing. On a particularly dark and rainy night, the cinema plays its final film: a revival of King Hu’s 1967 wuxia epic Dragon Inn. The narrative meanders across a few characters, each navigating their own solitude and sense of longing. There’s the kind cashier (Chen Shiang-Chyi), a quiet and observant woman, limping across the hallways, tending to her chores. She tries to find the projectionist (Lee Kang-Sheng) to give him a steaming hot bun but is unable to find him anywhere. One of the patrons (Chen Chao-Jung) says to a Japanese tourist (Kiyonobu Mitamura) soliciting sex, “Do you know that this theatre is haunted?”.

These characters move through the dark and dilapidated corridors, their presence accentuating the vast emptiness of the once-vibrant theatre. Taiwanese master of slow cinema Tsai Ming-Liang captures the eerie emptiness of a cinema turned into a ghost town in Goodbye, Dragon Inn. As the classic martial arts movie plays on the screen, its themes of betrayal, loyalty, and honor echo in the quiet and empty theatre. The juxtaposition of the old film with the decaying modern theatre highlights the passage of time and the inevitability of change. Through its deliberate pacing and Tsai’s signature minimalist approach, the film captures the essence of a fading era of cinema while also offering a poetic reflection on the passage of time.

22. Tropic Thunder (2008)

An action-comedy directed by and starring Ben Stiller, Tropic Thunder takes the viewer on a wild ride, generating laughs at the expense of Hollywood’s absurdities. Picture a bunch of pampered and self-absorbed actors – including Stiller, Robert Downey Jr., Jack Black, and Tom Cruise – thrown into a real jungle while filming the adaptation of a Vietnam war veteran’s memoir guerrilla-style. Damien Cockburn (Steve Coogan), the director of the movie within the movie, also called “Tropic Thunder,” comes up with this idea to inspire some authenticity in his actor’s performances. However, Damien dies early after stepping on a landmine and leaves his crew of actors to fend for themselves in this jungle, which also houses a ruthless gang of heroin makers.

The actors, incredibly enough, think that Damien must have faked his death to encourage his cast and keep moving according to the map and scene listings given to them. Things soon take a perilous turn as one of the actors, Tugg Speedman (Stiller), is captured by the drug gang, and the delirious Speedman mistakes the gang’s base camp for a location from the shooting script. Tropic Thunder isn’t simply a laugh riot but also takes swings at the mainstream film industry’s culture of self-importance and celebrity and the sometimes ridiculous lengths actors go to for authenticity. Parodying many war films and some real-life Hollywood personalities, this rollercoaster of satire doubles as a witty reflection on the industry’s quirks, which still hits the mark today.

23. Supermen of Malegaon (2008)

Made by Faiza Ahmad Khan, the documentary Supermen of Malegaon depicts the cinephilia that gripped the small town of Malegaon thanks to the circulation of pirated CDs and DVDs. Inhabited by impoverished slum-dwellers, Malegaon is transformed into a mini Hollywood as the locals collaborate to produce cheap parodies of famous films – one such film being the 1978 Christopher Reeve-starring Superman – using whatever resources they can find at their disposal. While the hairstyles of movie stars are appropriated by young men desirous of identifying with the Shah Rukh Khans and Sanjay Dutts, plots and characters from big-budget movies are appropriated by ‘pirate’ filmmakers similarly dreaming of being the Spielbergs and Chaplins of Malegaon. The film aptly demonstrates what unfolds when desires to participate in the cash-strapped world of cinema confront the sheer lack of economic infrastructure.

We see Sheikh Nasir, the man producing and directing ‘Malegaon ka Superman,’ approach a studio to obtain an estimate of how much it might cost him to implement chroma keying (the ‘legal’ way) for his film. Finding that legal access to the software and the required setup would cost him four times the total budget of his production, Nasir, refusing to give up, finds a way to drape a green screen over a truck to simulate similar effects at a fraction of the cost. Khan’s documentation of Malegaon’s ‘cinephilia’ invites us to reconsider the scope of that word insofar as the town embraces cinema not only within video halls and editing rooms but also within barbershops, tea stalls, and photo booths–a film industry blossoming beyond the production and distribution circuits of films themselves.

24. The Artist (2011)

Michel Hazanavicius’ comedy-drama The Artist is a delightful homage to the era of silent cinema, dramatizing Hollywood’s epochal shift to the talkies with the advent of sound film. It follows the life of George Valentin, a silent film star portrayed by Jean Dujardin. Valentin’s career takes a nosedive with the arrival of talking pictures, and the film explores the personal and professional challenges he faces in adapting to this industry shift. In contrast, rising star Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), also Valentin’s love interest, finds success in the world of talkies, creating a narrative tension between the two leads and mirroring the divide between Hollywood’s silent and sound eras.

To drive home its thematic preoccupations, The Artist is presented as a silent film without spoken dialogue, except at the end when Valentin gives up his stubbornness and joins the talkies. Hazanavicius skillfully incorporates classic film techniques, such as expressive acting and visual storytelling, to create an authentic silent film experience. In one memorable sequence depicting Valentin’s dream, we see (and hear) him hearing sounds from his surrounding environment even as he himself cannot speak – an omen of how Valentin stands to lose his artistic voice if he doesn’t flow with the times and accept the talkies like others around him seem to have. The Artist received widespread acclaim and numerous awards, including five Academy Awards, among them the Best Picture award and Best Actor for Dujardin.

25. This is Not A Film (2011)

In 2010, the Islamic Revolutionary Court in Iran sentenced Jafar Panahi to a 20-year ban from making or directing any movies or writing screenplays. In response, the very next year, Panahi used his iPhone to shoot This is Not a Film entirely from within the confines of his apartment and smuggled it out of the country and into Cannes via a flash drive hidden inside a birthday cake. It opens with a static shot of Panahi’s apartment door, and we hear him engaging in a conversation with his co-director, Mojtaba Mirtahmasb. Panahi sets the stage by elaborating on the circumstances that constrain the film, the various state-imposed restrictions which, despite their prohibitive nature, also define the playing field which Panahi can work with. As the narrative unfolds, Panahi takes the audience through his daily routines and interactions, capturing the mundanity of his life under house arrest.

One of the central elements of This Is Not a Film is Panahi’s exploration of storytelling and the role of a filmmaker. Despite the ban, Panahi engages in a creative act by reading the screenplay of a film he had intended to make, also titled “This Is Not a Film,” eventually stopping with the exasperated remark: “If we could just tell a film, then why bother making one?”. Frustrated by his inability to shoot the movie, Panahi decides to reenact some scenes from the screenplay within the confines of his apartment, the gesture serving as a powerful metaphor for the limitations imposed on him as an artist. Throughout the documentary, there’s a constant sense of tension and uncertainty as Panahi awaits the verdict of his appeal.

26. Berberian Sound Studio (2012)

Peter Strickland’s second feature, Berberian Sound Studio, is one unique psychological horror film exploring the intricacies of sound design and how the cinematic medium blurs lines between reality and fiction. It stars Toby Jones as the British sound engineer Gilderoy, renowned for his work on nature documentaries, arriving in Italy to work at the Berberian Sound Studio, expecting to record sounds for a documentary about horses. A meeting with the producer Francesco (Cosimo Fusco), however, reveals that the project is a gruesome Italian giallo titled “The Equestrian Vortex.” As Gilderoy immerses himself in his work, encountering scenes involving sadistic violence, mutilation, and horrifying screams – all of which Gilderoy must recreate – the boundaries between the real world and the film studio start to blur.

As Gilderoy becomes more entrenched in the production, his mental state deteriorates. Feeling out of his depth, he struggles to maintain a sense of reality as the studio environment, with its eccentric director and crew, takes on an increasingly surreal character. Berberian Sound Studio’s strength lies in its ability to conjure tension from the mundane – the whirring of tape reels, the clinking of props, and Foley artists mimicking gruesome sounds with vegetables. The absence of visual horror allows the audience’s imagination to run wild, contributing to the film’s overall sense of unease. Berberian Sound Studio becomes a meditation on the power of sound in the context of cinema – a predominantly visual medium – with the eerie and unsettling nature of the fictional horror production revealed solely through Gilderoy’s reactions and the sounds he creates.

27. The Disaster Artist (2017)

The year 2003 saw the release of The Room, a romantic melodrama made so poorly that it can only induce comic laughter and is commonly referred to as “the best worst movie ever.” But far more interesting than The Room is the man behind the film, its writer-director-producer and star Tommy Wiseau, and the story of how this impossible film actually got made. It is this story that is the subject of The Disaster Artist, a biographical comedy-drama directed by and starring James Franco as the inimitable Tommy Wiseau. The film explores the peculiar friendship between Wiseau and his co-star Greg Sestero (Dave Franco), taking us through the eccentricities and challenges that led to the creation of a cult classic – albeit for unintended reasons.

The Disaster Artist portrays Wiseau as a mysterious and enigmatic oddball figure with a seemingly bottomless bank account and a desire to make it big in Hollywood. Sestero is a struggling young actor in San Francisco who becomes fascinated and bewildered by Wiseau’s unabashed and unconventional approach to acting after seeing his bizarre take on a scene from A Streetcar Called Desire. The two of them move to Los Angeles together to pursue their dreams, and Wiseau decides to write, direct, produce, and star in his own film, “The Room,” fueled by a mix of passion and naivety. The Disaster Artist is no mere parody of its source film, however, but rather a heartfelt exploration of friendship, dreams, and the resilience of artistic ambition – especially when such ambition absolutely flies in the face of commonly held standards.

28. One Cut of the Dead (2017)

An ingenious blend of horror, humor, and meta-narrative, Shinichiro Ueda’s One Cut of the Dead is a Japanese zombie comedy featuring some of the most improbable plotting imaginable. It begins with a 37-minute single-take shot in a desolate, abandoned warehouse where a low-budget zombie film is being made, where the crew suddenly find themselves facing “real” zombies. The cast and crew fight for their lives, with the shaky camerawork and amateurish acting giving the impression of a genuine, unscripted zombie attack. Things take an unexpected turn, however, after the opening single-take act, as the film reveals itself to be a movie within a movie.

The narrative takes a step back to showcase the behind-the-scenes process leading up to the shoot, which is revealed to be for a live show, also called “One Cut of the Dead,” hence needing to be pulled off without delays or reshoots. The final act returns to the opening scene, at the beginning of the 37-minute single-take, but from a new perspective, letting us see the artifice behind what we initially took to be ‘natural.’ One Cut of the Dead cleverly subverts expectations, transforming what initially appears to be a generic zombie horror film into a celebration of the art of independent low-budget filmmaking with its meta-narrative structure. It derives its humor organically by juxtaposing the chaotic and amateurish first take with the subsequent scenes, revealing the meticulous planning and teamwork that went into the final product.

29. Black Bear (2020)

Lawrence Michael Levine’s Black Bear may initially seem like a straightforward drama but soon takes a sharp turn into mind-bending psychological territory as the narrative begins playing with the boundaries between reality and fiction, leaving the viewer perplexed by what they see unfolding. It is bookended by the singular scene of a young woman named Allison (Aubrey Plaza) sitting at the edge of a foggy lake and then retreating into a cabin to write something on her notepad. Allison is a filmmaker and former actress seeking solitude and inspiration and arrives at a lake house in the Adirondack Mountains owned by the couple Gabe (Christopher Abbott) and Blair (Sarah Gadon). But the seemingly idyllic setting becomes the stage for a simmering emotional drama as dynamics between the characters take unexpected turns.

Allison’s presence disrupts the delicate balance in Gabe and Blair’s relationship. On the one hand, we see flirtatious undercurrents between Allison and Gabe, and on the other, Blair’s dissatisfaction with her own life – compounded by her pregnancy and her husband’s failing musical career – begins to surface. With tensions escalating, the film takes an unexpected turn, challenging the audience’s understanding of the reality presented in the first part by introducing a metafictional layer. The setting remains the same, but everything is revealed to be part of a film shoot, with Gabe as the director and Allison and Blair his actors in the film. Using the filmmaking process as a lens to examine the complexities of human relationships and the subjective nature of storytelling, Black Bear becomes a thought-provoking cinematic exercise that leaves its viewers with more questions than answers.

30. Babylon (2022)

Set in the roaring 1920s, Damien Chazelle’s epic Babylon paints a captivating portrait of Hollywood’s tumultuous transition from silent films to talkies. In this era of boundless ambition and unbridled excess, the film follows the intertwined stories of a few individuals seeking their fortunes in the glittering world of cinema. Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), a charismatic and roguish silent film star, finds his career teetering on the brink as the talkies begin to dominate the industry. Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie), an aspiring actress with an insatiable hunger for success, arrives in Hollywood with dreams of becoming a star. And Mexican immigrant Manny Torres (Diego Calva), nurses his passion for cinema while dreaming of making it big in America, despite having no formal training or connections in the industry.

Babylon chronicles the transformative impact of technology on the activity of filmmaking by showing how the advent of sound, almost paradoxically, made silence a virtue by contrast. In what’s perhaps the most memorable sequence from the movie, we witness how the atmosphere of moviemaking undergoes radical change with the coming of sound – from noisy and chaotic (during the silent era) to requiring pin-drop silence on set owing to the sensitivity of the microphones. Babylon also closes with an unforgettable montage of film clips tracing the evolution of filmmaking from its silent beginnings to the modern era of blockbusters and special effects – from Muybridge’s horse to Cameron’s Avatar (2009) – an emotionally resonant coda encapsulating the film’s themes of ambition, change, and the enduring power of cinema.