The Iranian film director Dariush Mehrjui (1939-2023), often credited as the creative force behind the development of the Iranian New Wave in the 1960s and 1970s, was more than a man of the moment. While his celebrated film Gav (The Cow, 1969) did introduce a new film language in Iran in the seventies in a relative and contextually bound sense, Mehrjui’s catalog of films shows a singular sensibility that was not particularly committed to any one film movement or manifesto. Gav is as different from The Cycle as both are from Banoo, Sara, Pari, Leila, The Pear Tree, Bemani, Santuri, et al., to name a few of his other acclaimed films.

The formal and ideological continuities that exist in Mehrjui’s films may be seen in the abiding social concerns that scaffold his films, stories of rural and urban poverty, the lives of rural and urban Iranian women, and the lives of disaffected Iranian youth. He told these stories on screen in a largely neorealist language with stunning expressionistic and symbolic interludes. But even such experimental moments in Dariush Mehrjui’s films have an understated and unmarked quietness to them that does not call attention to themselves as high cinematic art. Instead, we remember Mehrjui’s films for their explicit humanity.

As a filmmaker whose films were banned by both the Shah’s government and the post-revolution Islamic Republic government, Mehrjui’s charged film career came to an end when, as yet unidentified assailants murdered both Mehrjui and his wife Vahideh Mohammadifar inside their home in Karaj, Iran on October 14, 2023. Mehrjui was 83 years old. [Editor’s note: suspects are arrested, although uncertainties prevail].

Whether in India, France, or Iran, New Wave movements in film had a direct relationship with the progressive and modern literature of the times. In India, Satyajit Ray looked towards the regional and realistic novels of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay for his famed Apu Trilogy, canonical to the Indian New Wave. In France, Alain Resnais sought scripts from Marguerite Duras for Hiroshima Mon Amour (Hiroshima My Love, 1959) and Alain Robbe-Grillet for L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad, 1961).

Iranian New Wave directors and films also looked towards literature for inspiration. Dariush Mehrjui’s New Wave contemporary Amir Naderi adapted Tangsir (1973) from a novel by Iranian writer Sadeq Chubak. Bahman Farmanara’s Shazdeh Ehtejab (Prince Ehtejab, 1974) was based on another modernist novel by Houshang Golshiri. Poet and filmmaker Forough Farrokhzad’s acclaimed film Khaneh Siah Ast (The House is Black, 1963) is structured around her own incantatory poems along with excerpts from the Qur’an. Abbas Kiarostami, not formally of the Iranian New Wave but a beneficiary and descendant of the movement, made films heavily populated with the modernist lyricism of poets Sohrab Sepehri and Forough Farrokhzad.

Dairush Mehrjui belongs to the above intermedial literary tradition of filmmaking. He based both Gav and Dayereh-ye Mina (The Cycle, 1977) on the works of Gholamhosein Sa’edi, one of Iran’s foremost dissident and exiled writers. While the two films could not be more visually and formally different from each other, these early films point to the presence of two repeated film languages in Mehrjui’s films: one, a tight expressionistic interiority, almost like the equivalent of delirium, dreams, or nightmares in an individual’s mind, and 2) a documentary exteriority that tracks individuals in their environment.

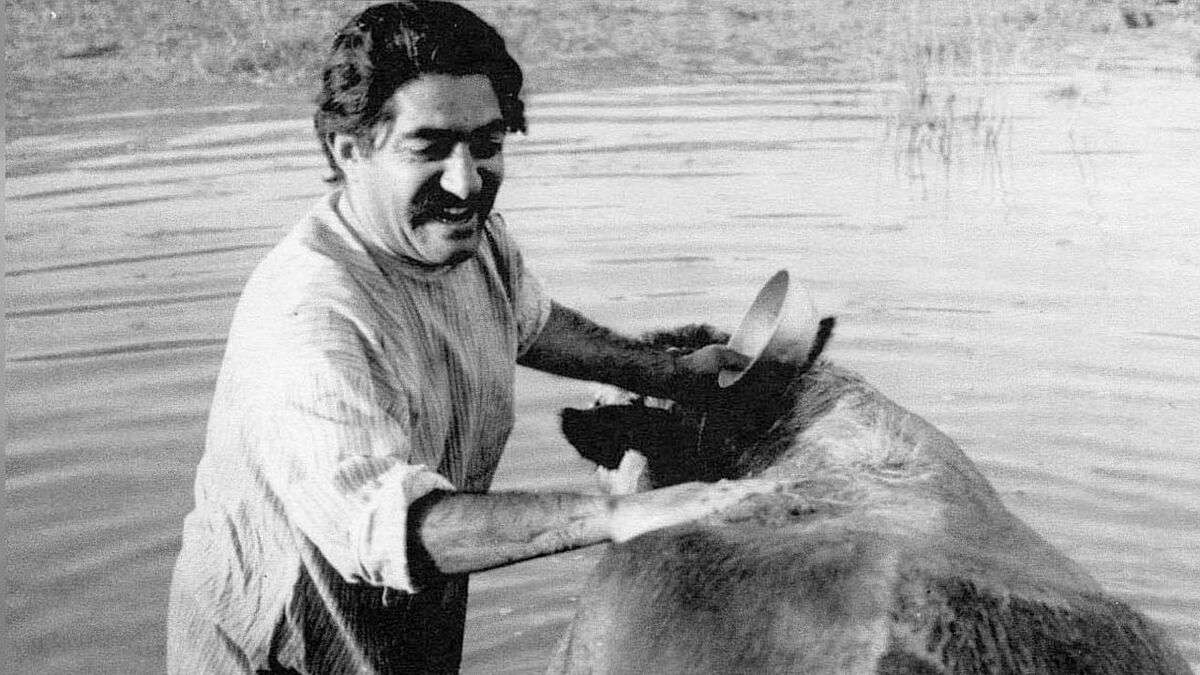

Gav tells the story of a simple village dweller, Masht Hasan, whose beloved cow dies on the day the story opens. The subsistence-level village considers this cow a true Kamadhenu, a blessed provider for one and all. Furthermore, Masht Hasan’s fondness for his cow has acquired a certain mythical reputation in the village as well. The film opens with an extended sequence of Masht Hasan washing his cow. Ezatollah Entezami, a regular in Mehrjui’s films, plays Masht Hasan with great innocence and love, but the extended takes also force us to confront a certain uneasy pride of possession between the man and the animal. Hasan washes himself in water, dripping off the cow’s body in the creek. The cow appears to have a totemic status for Hasan and even for the villagers because of their haste to keep its death a secret.

Because of Sa’edi’s own radical status before and after the Islamic Revolution of 1979—[he was arrested and tortured during the Shah’s reign for his dissident views, and he fled to France after the revolution because he feared for his personal safety ]– and because of such non-realistic representation of the man-animal bond, Gav has been interpreted as a political allegory for Iran’s painful birthing from tradition to modernity in an atmosphere contaminated by fear and paranoia about the future and a reluctance to give up what is already had and known. The film’s visual style encourages this inference: harsh, low-key lighting that reveals faces surrounded by dark shadows suggests a place and a time where much of what constitutes life or the future remains unknown and unknowable.

One of the most striking images in this category is the low-angle shots of the Boluri-ha on the hill, looking down at Masht Hasan and his cow. The Boluri-ha are thieves from a nearby village, and a substantial subplot involves their attempts to steal from Hasan’s village: is it the cow? Dariush Mehrjui creates night vistas of mystery, disquiet, and panic by immersing his screen in dark shadows and slivers of moonlight or lanterns eerily illuminating faces and limbs in a nighttime chase.

Beyond this expressionist visual design lies the thematic singularity of a man turning into a cow. While Hasan’s metamorphosis is not physiologically transformational—he retains his human form– he ceases to behave like a human and starts to imitate a cow. He moves to the cowshed near a cellar permanently, starts to chew hay, and sleeps on the floor. His bodily comportment changes, and Entezami brings a crazed, manic energy and stupor to Hasan’s incarnation as a cow. When Entezami becomes a cow, that transformation is not merely a species change but also a slippage into abjection, the kind of abjection that makes the milking scene in the darkened cellar in Kiarostami’s Bād mā rā khāhad bord (The Wind Will Carry Us, 1999) uneasy to watch with its intimations of a taboo spectacle.

Animals usually signify a form of mute powerlessness in Dariush Mehrjui’s films—the dog in Bemani is another example – and Hasan’s identification with the cow puts him at another species’ level of demasculinization and dehumanization. One that is not specifically cruel but more fittingly described as a punishment, a punishment for turning his back on humanity, on the village, on his wife, preferring his cow instead. Seen in this light, The Cow is as much a parable about the value of human life as it is a political allegory about tradition vs modernity.

The Cycle (1977) did for the lost urban youth of Iran in the years leading up to the revolution what Gaav did for lost villages and their women. Ali, the protagonist of The Cycle, is slightly older than Antoine Doinel, but he is just as aimless and lost as Truffaut’s truant twelve-year-old in Les Quatre Cents Coups (400 Blows, 1959). The Cycle is a peripatetic film where characters traverse long distances on foot and in vehicles, and their story is inscribed in their wanderings.

Shot in a semi-documentary manner with a neorealist eye for real locations, The Cycle ostensibly tells the story of the black-market blood bank business rife in Tehran in the seventies. Corrupt doctors, off-license clinics, seedy middlemen, and catatonic drug addicts who donate blood make up the main operators in this underworld. Ali, played with the right mixture of innocence and street smart by Saeed Kangarani, comes to Tehran to get medical treatment for his ailing father. Recognizing that they cannot afford the cost of treatment, they turn to selling blood in the underground market. Ali becomes the corrupt doctor’s errand boy in the grifter’s world.

Inside the scripted narrative of Ali’s story, there are enough discursive openings that connect the story to seventies social issues – the black market for blood issue — in an explicit manner, but what endures in the film is the final freeze frame of Ali at his father’s graveside. Dariush Mehrjui’s ending is decisively different from Sa’edi’s novel, on which the film is based, where Ali denounces the corrupt doctor to the Shah’s secret police, thereby implying his own compromised status. But Mehrjui’s freeze frame is a morally pregnant one with unknown possibilities for Ali—where does Ali go from the graveside? What world waits for him? Ali and Antoine Doinel ask the same question. Once again, Dariush Mehrjui comes back to a philosophical question.

Dariush Mehrjui made films based on non-Iranian stories as well. The 1983 documentary Journey to the Land of Rimbaud, Sara (1993), based on Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, Pari based on J. D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, and Leila (1996) testify to his deep and wide familiarity with world literature. Along with The Cow and The Cycle, Leila exemplifies the most concentrated form of certain repeated themes in Mehrjui’s films. Dariush Mehrjui, in his interviews, talked about how he was always trying to see how far he could go while working inside the constraints of censorship in Iran to make the films he wanted to make about issues that matter to him.

In Hamoun, Banoo, Sara, Leila, Pari, The Pear Tree, and Bemani, he again and again told stories of young girls and women, girls who want education, girls who want to be free and discover themselves, married women who seek love, married women who want to be free to leave their marriages, married women who love their husbands.

In Leila, one of Iran’s best women’s films, the titular character, Leila, breaks off all relations with her husband, Reza, when his mother forces him to take a second wife. Against her husband’s wishes—he loves her and does not want a second wife, he says—she selects her husband’s second wife herself, prepares him for the wedding, and then leaves him. In a key scene in the film, right after Leila finds out that she cannot conceive and that her mother-in-law is forcing her husband to take another wife to bear him a child, the couple sits in their home and watches Dr. Zhivago (David Lean, 1965).

The screen fills with the faces of Yuri (Omar Shariff) and Lara (Julie Christie) in a ruined, desolate, and frozen castle in the middle of nowhere, where they consummate their tragic love for each other. Later, Yurii watches from the window when Lara drives away with the comrades from the Red Army as “Lara’s Theme” swells in the background. It is love in times of war.

It is a gentle displacement, but Dariush Mehrjui redefines Leila’s and Reza’s relationship not as that of a wife and a husband but as that of lovers operating inside forces they cannot control. Lean’s adaptation of Pasternak’s novel (in Robert Bolt’s excellent screenplay) begins with a recognition scene of Yuri’s half-brother Yevgraf Zhivago (Alec Guinness), a colonel in the Red Army recognizing a young woman in a factory line-up as Yuri’s and Lara’s child, Tanya Komarova. The right people are all married to the wrong partners.

Dariush Mehrjui’s film ends with a recognition scene. Leila sees her husband, Reza, now single, walking into a family feast with a little girl, his daughter, holding his hands. Leila’s quiet voice-over matches the mysterious half smile on her face as she notes that the young girl Baran would know that she was born only because of her mother’s insistence. That is Leila’s insistence. Love is often the overdetermined element in Mehrjui’s films. Thus, the final union between a half-burned Bemani and the graveyard assistant in Bemani. Why would anyone want to deny the power of love when so much suffering is engendered because of its absence?

More than many other modern directors in Iran, Mehrjui’s films, with their exquisite mise-en-scene framing, give us a sense of the material world of ordinary people in Iran both in the pre and post-revolution years. Films like The Cow, The Cycle, Hamoun, Banoo, Sara, Pari, Leila, The Pear Tree, Bemani, and Santuri et al., depict a world filled with the colors and textures of food, furniture, clothing, animals, trees, flowers, wind, curtains, carpets, mountains, alleys, cellars, streets, hospitals, children, teenagers, addicts, floors, windows, and possessions of the impoverished, the rich and everyone in between. Perhaps this phenomenological insistence that if you reflect the surface truthfully, you are bound to reflect the depths truthfully must be a lesson Dariush Mehrjui learned from the great modernist writers he emulated in his film craft. With his passing, world cinema has lost one of its visionary storytellers.

Read More:

K. G. George and the Craft of Flashback

Why Are Michael Haneke Films So Disturbing?

Raj Kapoor – Director’s Study

![The Cow [1969] – A Pioneering Masterpiece of Iranian Cinema](http://www.highonfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The-Cow-cover-768x432.jpg)