“Killers of the Flower Moon” and the Politics of Martin Scorsese: If there were a film in Martin Scorsese’s oeuvre that I’d label as an “outlier,” it would likely be Silence. I distinctly recall the dreamlike murkiness of Taxi Driver, the irresistible suave of Goodfellas, and the indulgent comedy of The Wolf of Wall Street. However, only a few works have left an impression as strong as Silence for me. Much like its name, the film is tonally reserved. It deviates from the classic Hollywood gangster flick that has become partially associated with Scorsese. Instead, it reminisces the Japanese masters, namely Kenji Mizoguchi and Akira Kurosawa (both are significant inspirations for Scorsese).

The film’s aesthetics have a transfixing formal simplicity, and the gradual manner in which the story beats unfold is unrelentingly interrogative. Rodrigues’ journey there captures both the sharpest pains and deepest catharses of humanity, which is apt for the biblical nature of the text.

The Banality of Crime in Killers of the Flower Moon

There is no leniency in Silence’s depiction of the violence and dread that the persecuted Christians experienced in 17th-century Japan. Harrowing moments of execution and apostasy scatter a largely mediative and tranquil narrative. In Scorsese’s latest feature, Killers of the Flower Moon, the calculated slaughter of the Osage people shares less with Silence than it does with Scorsese’s second most recent film, The Irishman. Both Killers of the Flower Moon and The Irishman recall the aura of the classic American gangster flick that popularised Scorsese for much of the film community. Still, more notably, both works share a certain coldness that stamps the life out of characters and their actions.

The murders in these films forgo all emotion for an entirely procedural tone. Each death is either just a task to be completed for a financial incentive or a loose end that needs to be tied up. And even though such an approach has fostered some criticism regarding the lack of attention given to the Osage community in the film, it’s a fitting tone to establish for a film that takes a look at imperialism from the perspective of the imperialist.

Other 2020s films have also taken on this attitude in their attempt to illustrate the callousness inherent to America’s advancement as a country as well as its environment in the 21st century. The former is touched upon in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, which captivates with its rhythms of scientism flowing through the US military-industrial complex and academia, only to end on an unforgettable image that depicts the end result of what the film calls “the chain reaction.” The latter is a central interest in David Fincher’s The Killer, where the director’s 90s nihilism is satirized and sharpened into a runtime of taciturn artificiality.

Scorsese’s Delineation of Racism and American Imperialism

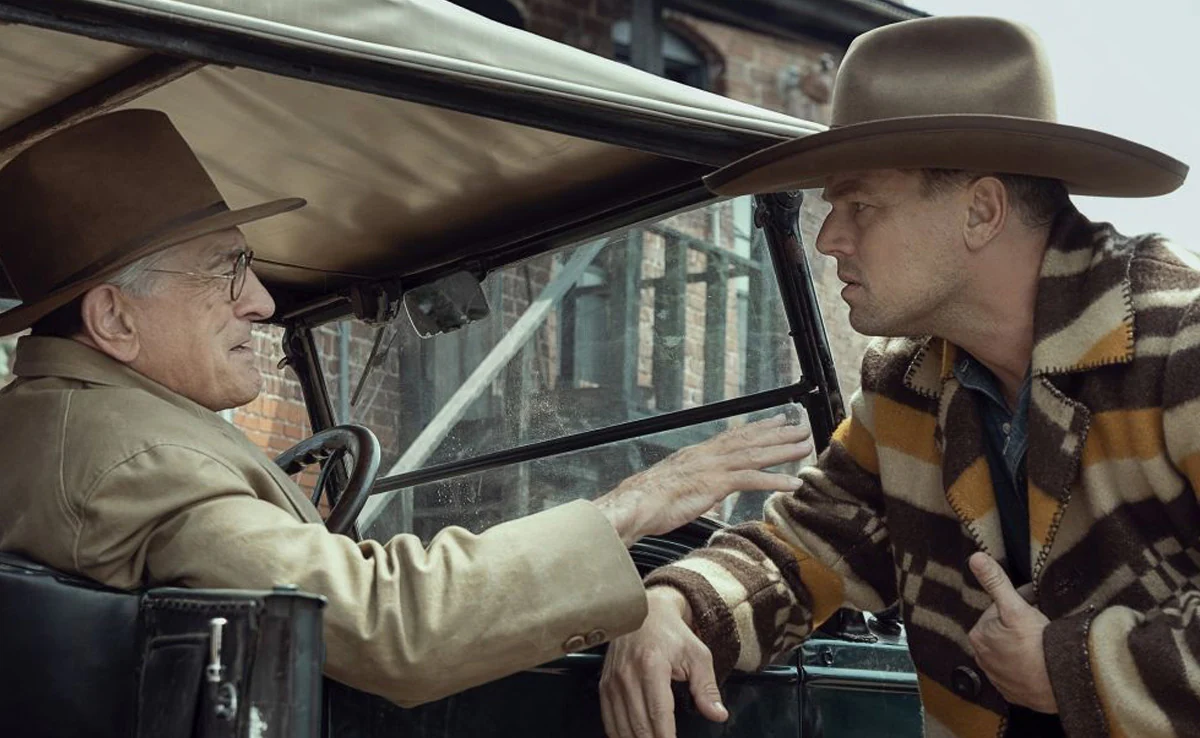

Killers of the Flower Moon concentrates its banality on its two imperialistic main characters, William King Hale (Robert De Niro) and Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio). Hale instructs Burkhart within the setting of the Osage nation, manipulating him into betraying his own spouse, murdering the native members, and stealing their property. De Niro perfectly plays his character like an ostensibly well-intentioned politician, expressing zero hatred for the Osage and instead even complimenting them here and there. There’s a clarity to Scorsese’s portrayal of racism here (which he has shown in his previous works, too, namely Taxi Driver), rendered with dehumanizing condescension rather than any intense sentiments.

However, the motivation behind this polite façade is, of course, that of malicious greed, a foundational building block of America’s economic-political system. But even then, The Bureau of Investigation eclipses Hale, reminding us that he’s just another cog in the imperialistic engine who controls an even smaller cog (Burkhart). Just like how Burkhart deceives his Osage wife, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), Hale tricks Burkhart for his own gain.

The uncle-nephew relationship between Hale and Burkhart is, then, also that of the self-interested colonialist and his hapless associate whom he makes use of. In this way, the film structures itself into layers of fraud, painting its portrait of America not with the blunt ruthlessness of mass-theft/murder but rather with the poignant stream of lies and disillusionment.

The American View and Sublimity in the Osage Scenes

At the heart of the film is the Osage community, but the perspective taken on them is, as mentioned before, that of the imperialists. So, it is understandable why Scorsese maintained a certain distance from the Osage people in the film since he knows he can’t fully empathize with their experience. The natives are constantly sidelined in the film’s eyes, just as they were by European settlers. Comparable to Nolan’s omission of Japanese suffering as a result of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in Oppenheimer, Scorsese doesn’t want to reduce his film down to a simplistic portrayal of grief. Instead, he scrutinizes the American view on its native population and how that contributed to the feasibility of their murder with no consequence.

Still, even with this distance, Scorsese infuses scenes with the Osage people with a sublimity that often reminded me of the liberating grace of Malickian cinema. In particular, an early scene depicts the death of Mollie’s mother. As she passes away, the soundscape clears, and there’s an image of her meeting other deceased members of her community as the living mourn intensely with their cries silenced in the sound design. Hallucinations of owls (an indication that death is close by in the Osage culture) is another example of this category of transcendental filmmaking that intersperses the stream of institutionalized and rationalized evil that imbues most of the film.

As a result, Killers of the Flower Moon is not entirely devoid of hope despite the inherent bleakness of its subject matter. In the end, Hale and Burkhart got off easy (released on parole and pardoned, respectively), and Scorsese states sorrowfully in his most notable cameo that “There was no mention of the murders.” And even with its fittingly satirical coda, there’s a humility to the film’s finale, particularly in the choice of devoting its final image to the Osage people. It’s a clear indication of Scorsese’s acknowledgment of colonial institutionalized viewpoints, his inability to fully fathom the other side, and, above all, his primary concern with humanity.

Read More: 15 Best Martin Scorsese Pictures

![The Columnist [2020]: ‘Fantasia’ Review – An entertaining ride with a timely subject in its hold lead by a phenomenal Katja Herbers](http://www.highonfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-Columnist-Movie-Review-highonfilms-2-768x432.jpg)

![Trenque Lauquen [2022] ‘Venice’ Review: A Curious Mystery That Paints A Fragmented Portrait of a Woman](http://www.highonfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Trenque-Lauquen-2022-Venice-Review-768x432.jpeg)

![Return to Seoul [2022] Review – A Masterful character study of a life stuck in the in-betweens](http://www.highonfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/RETURN-TO-SEOUL-768x432.webp)