While not as widely popular as his peer Akira Kurosawa, few filmmakers have left as indelible a mark in film history as Yasujiro Ozu. His body of films, at first glance deceptively simple in their focus on Japanese family life, reveals themselves to be profound explorations of the human condition, transcending cultural and temporal boundaries with their universal themes and emotional resonance. From the pre-war period through the occupation and into the economic boom of the 1950s and early 60s, Ozu’s works serve as a gentle yet piercing chronicle of a nation caught in flux.

However, to categorize Ozu merely as a chronicler of Japanese society would be to undersell the true scope of his artistry and the universality his narratives attain. Initially overlooked internationally due to their perceived “Japanese-ness,” his works gained recognition in the West largely after he died in 1963. His famous “tatami shots” – static camera positions set low to the ground, approximating the viewpoint of someone seated on a traditional Japanese tatami mat – create a sense of intimacy and quiet observation.

Related Read: 10 Best Films of Akira Kurosawa

Equally iconic are Ozu’s “pillow shots” – brief cutaways to landscapes, empty rooms, or seemingly unrelated objects that punctuate the narrative. They provide a rhythm to the storytelling, offer moments of reflection for the audience, and often function as visual metaphors that deepen the thematic resonance of the scene. A gently swaying clothesline or a solitary vase can speak volumes about the passage of time or the emotional state of characters. Ozu’s characters often communicate more through silence and small gestures than through dialogue, creating a rich subtext that rewards attentive viewing.

So be patiently seated on your tatami and grab a glass of sake as we dive deep into the twenty best works from Yasujiro Ozu’s career, films that will certainly leave you profoundly transformed if not emotionally devastated.

20. A Hen in the Wind (1948)

A harrowing exploration of the moral and psychological devastation wrought by World War II on Japanese society, “A Hen in the Wind” is something of a departure from Ozu’s typical domestic dramas as it descends into some of the darker recesses of human experience. Tokiko (Kinuyo Tanaka) is a young mother grappling with the harsh realities of life in Tokyo amidst the inflation of prices following the war. With her husband Shuichi (Shuji Sano) yet to return from his military service, Tokiko ekes out a meager existence for herself and her four-year-old son Hiroshi. When Hiroshi falls ill and requires hospitalization, Tokiko finds herself in an impossible situation. Faced with mounting medical bills and no means to pay them, she makes the heart-wrenching decision to sell her body for a single night.

This act of desperation, arising from a mother’s love, becomes the fulcrum upon which the rest of the narrative turns. Shuichi unexpectedly returns, and with Tokiko’s secret weighing heavily on her conscience, she confesses to her husband about her act, only to be met with a reaction of shock and disgust. At its core, “A Hen in the Wind” is a meditation on the nature of sacrifice and the blurring of moral lines in times of extreme hardship. Despite working with limited resources in a country still reeling from war, Ozu manages to create a world that feels authentic and lived-in. The sparse interiors and rubble-strewn streets silently become characters in their own, their presence a constant reminder of the hardships the film’s protagonists face.

19. An Inn in Tokyo (1935)

Ozu’s final silent film is a quietly devastating portrait of Depression-era Japan, showcasing the director’s growing mastery over his craft. Often overlooked in discussions of Ozu’s oeuvre, “An Inn in Tokyo” depicts the endurance of human dignity in the face of grinding poverty, offering a haunting glimpse into the lives of those struggling at the margins of society. We follow Kihachi (Takeshi Sakamoto), an unemployed laborer wandering the industrial outskirts of Tokyo with his two young sons, Zenko (Tokkan Kozo) and Masako (Takayuki Suematsu). Their days are spent in a seemingly endless search for work and food, with Kihachi doing his best to maintain a semblance of normalcy for his children despite their dire circumstances.

As they traverse the bleak landscape of factories and vacant lots, the trio’s path intersects with that of Otaka (Yoshiko Okada), a single mother struggling to care for her sick daughter Kimiko (Kazuko Ojima). Kihachi and Otaka feel a sense of kinship between them, two souls united by their shared hardship and parental devotion. When Kimiko’s illness worsens, Kihachi faces a moral dilemma: should he use the money he’s finally earned to help Otaka pay for her daughter’s medical treatment or prioritize his own children’s needs? This ethical quandary forms the crux of the film’s latter half, leading to a conclusion that is simultaneously heartbreaking and strangely hopeful. Ozu’s choice to film in actual industrial areas around Tokyo adds a layer of authenticity to the narrative, immersing viewers in the bleak environment faced by the characters.

18. The Munekata Sisters (1950)

Based on a novel by Jiro Osaragi, “The Munekata Sisters” is a nuanced exploration of postwar Japan through the lens of family dynamics and unfulfilled romantic longings. It is more melodramatic than his usual domestic dramas and acts as a bridge between his earlier works and the more refined masterpieces of his late career. The film centers on two sisters: the traditional and reserved Setsuko (Kinuyo Tanaka) and the more Westernized and outgoing Mariko (Hideko Takamine). Their lives are inexorably altered by the reappearance of Hiroshi (Ken Uehara), a former flame of Setsuko’s who has maintained a friendship with Mariko. This triangular relationship forms the emotional core of the narrative, with each character grappling with unspoken desires and societal expectations.

Setsuko, unhappily married to the alcoholic Mimura (Chishu Ryu), finds her dormant feelings for Hiroshi rekindled. Being aware of her sister’s past and present hardships, Mariko attempts to reinvigorate the romance between the two former lovers despite her own growing affection for Hiroshi. Their sisterly bond is put to the test by their conflicting desires and sense of duty. Ozu’s famous “pillow shots” – seemingly unrelated cutaways to landscapes or objects – punctuate the narrative, creating a meditative rhythm and subtly reinforcing the themes of transience and unfulfilled longing. The film’s depiction of Setsuko’s unwavering sense of duty versus Mariko’s pursuit of personal happiness serves as a microcosm of the broader societal shifts occurring in Japan during the period. While “The Munekata Sisters” retains Ozu’s trademark attention to detail and meticulous framing, it also exhibits a heightened sense of dramatic and emotional intensity.

17. A Story of Floating Weeds (1934)

A moving tale of a traveling theater troupe, “A Story of Floating Weeds” is a silent masterpiece foreshadowing the director’s later preoccupations with family dynamics and the bittersweet passage of time. The film centers on Kihachi (Takeshi Sakamoto), the aging leader of a struggling kabuki troupe that arrives in a small coastal town for a series of performances. Unbeknownst to his fellow actors, Kihachi has a secret: a son, Shinkichi (Koji Mitsui), whom he fathered years ago during a previous visit. Shinkichi was raised by his mother, Otsune (Chouko Iida), Kihachi’s former mistress, who believes Kihachi to be his uncle.

As Kihachi reconnects with his son and former lover, tensions arise within the troupe. Kihachi’s current mistress, Otaka (Rieko Yagumo), also the lead actress, grows suspicious of his frequent absences. Upon discovering the truth about Shinkichi, she manipulates a young actress, Otoki (Yoshiko Tsubouchi), into seducing the naive young man, hoping to hurt Kihachi in the process. Kihachi must ultimately choose between his responsibilities to his troupe and his long-suppressed wish to settle down with his family.

The film’s visual style is rich and evocative, with Ozu and his cinematographer, Hideo Shigehara, making exquisite use of light and shadow. Scenes of the troupe’s performances, with their theatrical lighting and exaggerated gestures, contrast beautifully with the naturalistic depiction of everyday life in the town. Ozu’s direction of the actors is masterful, eliciting nuanced, understated performances that convey volumes through the smallest gestures. The tension between tradition and modernity – embodied in the contrast between the traditional kabuki theater and the encroaching influence of cinema – is particularly prescient.

16. Record of a Tenement Gentleman (1947)

O-Tane (Choko Iida) is a middle-aged widow running a small shop in a tenement district. Her solitary existence is disrupted when her neighbor Tashiro (Chishu Ryu) brings home a young boy named Kohei (Hohi Aoki), who has been separated from his father. Despite her initial reluctance, O-Tane grudgingly agrees to take in the child for what she assumes will be just one night. As days pass and Kohei’s father fails to appear, O-Tane’s irritation gradually gives way to a complex mix of emotions. The boy’s presence forces her to confront her loneliness and the void left by her deceased husband and son. Meanwhile, Kohei, initially withdrawn and prone to bed-wetting, slowly begins to open up to O-Tane and the other tenement residents.

The plot unfolds with Ozu’s characteristic gentleness, eschewing dramatic twists in favor of subtle shifts in character relationships. When Kohei’s father is finally located, O-Tane finds herself unexpectedly conflicted about parting with the boy. Young Hohi Aoki delivers a performance of astonishing depth as Kohei. His silent suffering and tentative steps towards trust are heartbreakingly real. Ozu’s treatment of the theme of makeshift families is particularly poignant. The bond that forms between O-Tane and Kohei, as well as the wider community of the tenement, speaks to the ways in which people come together to fill the voids left by war and societal upheaval. The director’s sympathetic portrayal of these characters, flaws and all, is a testament to his deep humanism.

15. I Was Born, But… (1932)

A masterful silent comedy-drama exploring the pains of childhood amidst social hierarchies, “I Was Born, But…” sets itself apart from much of Ozu’s oeuvre with its humor and lightness of touch. It centers on two young brothers, Keiji (Tomio Aoki) and Ryoichi (Hideo Sugawara), who move to a suburban Tokyo neighborhood with their parents. Their father, Yoshi (Tatsuo Saito), works as a humble salaryman for a company executive, Iwasaki (Takeshi Sakamoto), who happens to live in the same neighborhood. As the boys struggle to fit into their new environment, they face bullying from the local children, particularly Iwasaki’s son. They eventually establish themselves at the top of the local pecking order through a combination of wit and bravado.

However, the boys’ newfound confidence is shattered when they witness their father acting subserviently and playing the clown for his boss during a home movie screening at Iwasaki’s place. This revelation triggers a crisis for the boys, who struggle to reconcile their image of their father as a respected figure with the reality of his place in the adult social hierarchy. They go on a hunger strike, demanding to know why their father debases himself like that.

Ozu deftly uses repetition and variation in shot composition to effect storytelling via minimalist means: recurring shots of the boys walking to school or the fathers leaving for work create a rhythmic structure that mirrors the routines of daily life while subtly highlighting the changes in the characters’ relationships and attitudes. His preference for static camera positions and carefully composed frames lend a sense of stability and assuredness to the film, contrasting with the tumultuous emotions of its young protagonists.

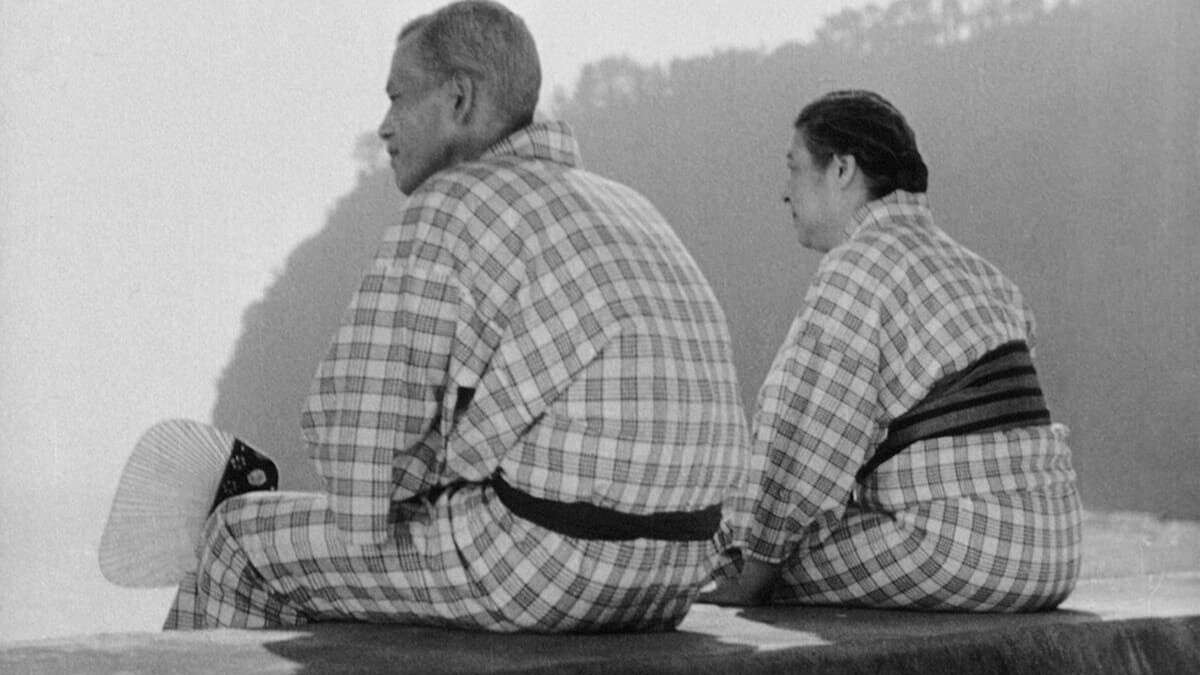

14. There Was a Father (1942)

Shuhei Horikawa (Chishu Ryu) is a widowed schoolteacher who decides to quit his job and move to Tokyo with his young son Ryohei (Haruhiko Tsuda) after a tragic accident during a school trip. Feeling responsible for a student’s death, Shuhei believes he’s no longer fit to teach. However, financial constraints force him to send Ryohei to live with relatives while he works to support his son’s education from afar. Shuhei’s dedication to his son is evident in his every action, as he balances his role as a father with his responsibilities as a teacher. As the years pass, we see Ryohei (now played by Shuji Sano) grow into a young man, following in his father’s footsteps as a teacher. Despite their physical separation, the bond between father and son remains strong, sustained by occasional visits and a shared sense of duty and responsibility.

The film’s latter half focuses on their reunions and the tension between Ryohei’s desire to live with his father and Shuhei’s insistence that they continue their separate lives for the greater good. Chishū Ryū’s performance as Shuhei is profoundly moving, capturing the character’s stoic dedication and inner turmoil. His portrayal of Shuhei’s unwavering sense of duty and quiet strength is complemented by Shūji Sano’s depiction of Ryohei, whose journey from childhood to adulthood is marked by a longing for his father’s approval and presence. Ozu’s thematic explorations in this film are deeply rooted in the cultural and historical context of wartime Japan, where notions of duty, sacrifice, and generational transmission of values were particularly salient.

13. The End of Summer (1961)

A bittersweet exploration of familial dynamics and generational shifts amidst the inevitability of change, “The End of Summer” is a late-career masterwork from Ozu that mines profundity within the everyday rhythms of Japanese family life. The aging patriarch of the Kohaygawa family, Manbei Kohaygawa (Ganjiro Nakamura), is the owner of a small sake brewery outside Kyoto. His daughters, the widowed Akiko (Setsuko Hara) and the divorced Noriko (Yoko Tsukasa), are facing pressure to remarry while Manbei, despite his declining health, indulges in carefree behavior like rekindling a romance with his old lover Tsune (Chieko Naniwa). This revelation, along with the declining fortunes of the brewery, forces the family to confront uncomfortable truths about their father and their future.

Like a lot of Ozu’s films, “The End of Summer” wrestles with the tension between tradition and modernity in postwar Japan. The declining sake brewery serves as a metaphor for the fading of old ways, while the daughters’ marital prospects represent the changing roles of women in society. One particularly striking sequence shows a series of empty rooms in the family home, hinting at the absence that will soon be felt. Ozu’s signature static camera and low-angle shots are omnipresent, but here, they serve to underline the film’s focus on the characters’ internal lives. Ganjiro steals the show as the irrepressible Manbei, his portrayal balancing humor and pathos, capturing both the character’s zest for life and his growing awareness of his mortality.

12. The Only Son (1936)

Ozu’s first full-length talkie, “The Only Son,” unfolds in two distinct parts separated by a 13-year time jump. In the rural silk-spinning town of Shinshu, we meet Tsune Nonomiya (Chôko Iida), a widowed factory worker struggling to raise her young son Ryosuke (Masao Hayama). When Ryosuke’s teacher Okubo (Chishû Ryû) encourages Tsune to send the boy to middle school in Tokyo, she makes the heart-wrenching decision to sacrifice her own comfort for her son’s future. The story then leaps forward to 1935, as an aging Tsune (still played by Chôko Iida) travels to Tokyo to visit the now-adult Ryosuke (Shin’ichi Himori). But her joy at reuniting with her son is tempered by the realization that his life hasn’t turned out as she’d hoped.

Ryosuke works as a night school teacher, barely making ends meet with his wife Sugiko (Yoshiko Tsubouchi) and infant son. As Tsune spends time with Ryosuke, she grapples with feelings of disappointment and guilt, questioning whether her sacrifices were worthwhile. Ozu deftly allows the emotional undercurrents to simmer beneath a placid surface with his characteristically restrained direction. His careful attention to detail—the way Tsune prepares a meal and the quiet moments of reflection—imbues the film with a lyrical quality that enhances its emotional impact. We see Tsune wandering alone through Tokyo, the bustling city, emphasizing her sense of displacement and the distance between her and her son. Chôko Iida’s stoic exterior barely conceals a wellspring of maternal love and disappointment, communicated through the subtlest changes in expression.

11. The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice (1952)

Taeko (Michiyo Kogure) and Mokichi Satake (Shin Saburi) are a middle-aged couple whose marriage has settled into a state of quiet dissatisfaction. Taeko, from an upper-class background, finds her husband’s simple tastes and unrefined manners embarrassing. While Mokichi, a salaryman content with life’s small pleasures, seems oblivious to his wife’s dissatisfaction. Their domestic stalemate is disrupted by the arrival of Taeko’s niece, Setsuko (Keiko Tsushima), who rebels against her family’s plans for an arranged marriage. Setsuko’s modern attitudes serve as a foil to Taeko’s more traditional outlook while also highlighting the generational shifts occurring in postwar Japan. As the story unfolds, a series of small incidents – including a white lie about a business trip and a night out at the pachinko parlor – bring the underlying tensions in the Satake marriage to the surface.

The sensitive and turbulent narrative culminates in a simple yet profound scene where Mokichi prepares ochazuke (green tea poured over rice) for Taeko, a humble dish that connotes their reconciliation and mutual understanding. As she watches Mokichi prepare and enjoy the meal, Taeko begins to realize the value of his sincerity and the quiet stability he offers. The performances are uniformly excellent, with Michiyo Kogure bringing a perfect blend of haughtiness and vulnerability to Taeko. On the other hand, Shin Saburi’s Mokichi is a masterclass in understatement, his seemingly impassive exterior hiding a deep well of affection and patience. Ozu presents both of their perspectives with the utmost empathy, showing how their different backgrounds and expectations have led to their current impasse despite their best intentions.

Also Related to Yasujirō Ozu’s Movies: 55 Best Japanese Movies of the 21st Century

10. Early Spring (1956)

Ozu’s longest surviving film, running at 144 minutes, is a nuanced examination of marital disillusionment, workplace ennui, and the complexities of human relationships in postwar Japan. Centering on the life of a young salaryman navigating the challenges of modern urban existence, “Early Spring” marks a departure from his usual focus on family dynamics within domestic settings. Shoji Sugiyama (Ryō Ikebe) is a bored white-collar office worker trapped in a loveless marriage with his wife, Masako (Chikage Awashima). Their relationship, strained by the loss of a child years earlier, has settled into a routine of quiet despair and grudging acceptance. Shoji’s discontent leads him into a brief affair with an office colleague, nicknamed “Goldfish” (Keiko Kishi), for her large eyes, setting in motion a series of events that force him to confront the emptiness of his life.

As the affair progresses, we see its ripple effects on the lives of those around Shoji. His wife Masako suspects his infidelity but remains stoic, while his colleagues gossip and speculate about the relationship. Ozu’s deliberate pacing and signature pillow shots —tranquil images of landscapes or interiors—provide reflective pauses that underscore the film’s contemplative tone. His depiction of Shoji’s infidelity is handled with sensitivity, focusing not on the sensationalism of the act but on the underlying emotional and psychological factors. The use of tracking shots, particularly in the office sequences, adds a sense of unease and disorientation, reflecting the characters’ internal turmoil. With its rigidly hierarchical and impersonal atmosphere, the office environment serves as a microcosm of the larger societal pressures faced by the characters.

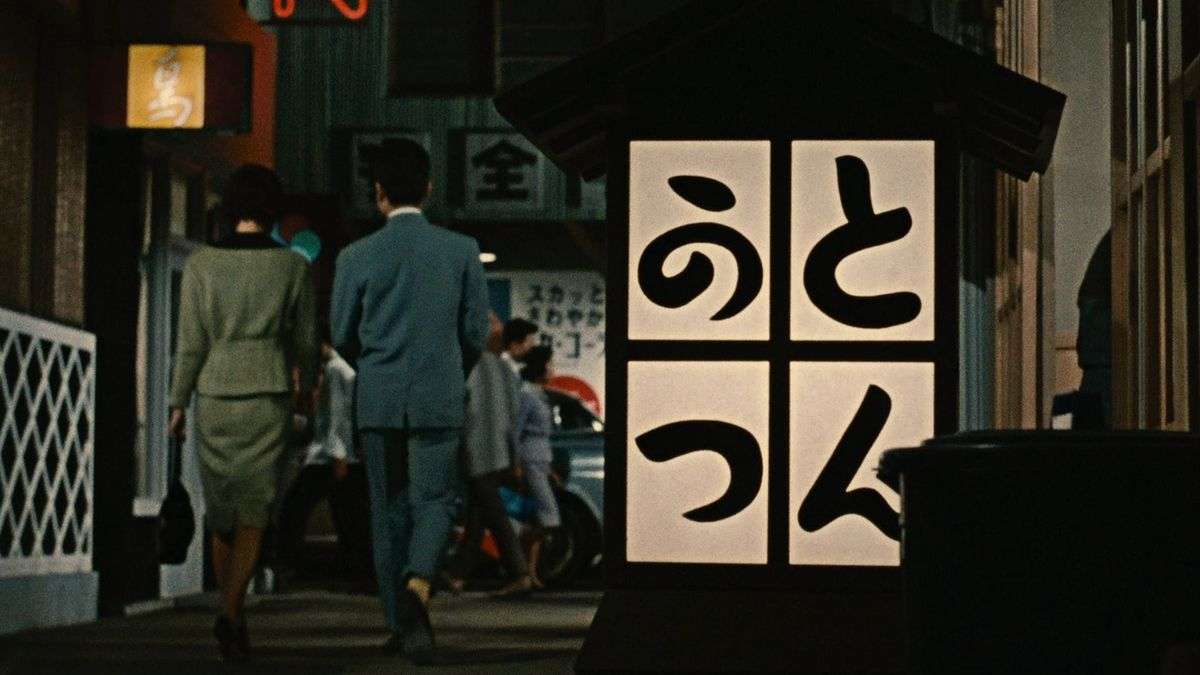

9. Equinox Flower (1958)

Ozu’s first color film is a gentle and beautifully shot exploration of generational conflict, foregrounding his central career-long preoccupation with the clash between tradition and modernity in a rapidly urbanizing Japan. We follow the tale of Hirayama Wataru (Shin Saburi), a successful businessman who prides himself on his modernized liberal attitudes. However, his progressive facade is put to the test when his daughter Setsuko (Ineko Arima) announces her intention to marry a man of her own choosing rather than submit to an arranged marriage. Forced to confront the gap between his professed beliefs and his deeply ingrained traditional values, we see Hirayama navigate a series of encounters that highlight his internal conflict.

Hirayama advises his daughter’s friend Yukiko (Fujiko Yamamoto) to defy her parents and marry for love, yet struggles to apply the same principle to his own daughter. His wife, Kiyoko (Kinuyo Tanaka), and younger daughter, Hisako (Miyuki Kuwano), serve as sounding boards and gentle critics of his inconsistent stance. As Setsuko remains firm in her choice, Hirayama’s stubbornness creates a rift between him and his daughter. Ozu’s punctuating pillow shots take on new life in color, with the vibrant reds of the equinox flowers (higanbana) serving as a recurring visual motif, echoed in other elements throughout the film: from a character’s clothing to a tea kettle, creating a visual continuity that reinforces the film’s themes. These flowers, associated in Japanese culture with death and the afterlife, subtly underscore the theme of passing from one era to another.

8. Late Autumn (1960)

Based on Ton Satomi’s novel of the same name, “Late Autumn” is a late-career masterpiece from Ozu centering on Akiko Miwa (Setsuko Hara), a widow in her late thirties, and her daughter Ayako (Yoko Tsukasa) who is of marriageable age. Three of Akiko’s husband’s old friends – Taguchi (Nobuo Nakamura), Gotoda (Ryuji Kita), and Mamiya (Shin Saburi) – take it upon themselves to find a suitable husband for Ayako, feeling a sense of obligation to their deceased friend. But as their matchmaking efforts progress, complications arise. The men begin to reminisce about their own youth and their past attraction to Akiko, leading them to consider the possibility of remarriage for her as well.

Meanwhile, Ayako resists the idea of marriage, not wanting to leave her mother alone. This creates a gentle tension between mother and daughter, each concerned for the other’s happiness at the expense of their own. Ozu’s ability to find beauty in the ordinary is evident in every frame. At its heart, the film is an exploration of the cyclical nature of life, with the older generation seeing their youth reflected in Ayako while confronting their own aging.

This theme is embodied in the film’s Japanese title, “Akibiyori,” which refers to clear autumn weather: a metaphor for the bittersweet beauty of life’s later stages. Akiko and Ayako represent different generations, with Ayako’s reluctance to marry reflecting shifting attitudes toward traditional expectations for women. Ozu treats this theme with characteristic subtlety, allowing the characters’ actions and conversations to speak volumes about societal changes. The autumnal palette reinforces the film’s themes of maturity and the passage of time.

7. Floating Weeds (1959)

Remaking his own 1934 silent film in color and with sound, Ozu conjures a poetic treatment of a struggling traveling theater troupe in a small Japanese coastal town to weave through themes of family, longing, and the ephemeral nature of life and attachments. We follow Komajuro (Ganjiro Nakamura), a seasoned kabuki actor leading a struggling theatrical troupe, arriving in a seaside town for a series of performances. But unbeknownst to his fellow actors, Komajuro has a hidden plan: to visit his former lover Oyoshi (Haruko Sugimura) and their son Kiyoshi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), now a young man who believes Komajuro to be his uncle. As Komajuro attempts to reconnect with his son, tensions arise within the troupe – particularly with his current mistress, the actress Sumiko (Machiko Kyo).

As the troupe’s performances fail to draw crowds, financial pressures mount, mirroring the emotional tensions between the characters. Vibrant reds and blues in the theater scenes contrast with the muted tones of the town, visually underscoring the divide between the performers’ public and private lives. Ozu’s meticulous framing often places characters in doorways or behind screens, subtly reinforcing the theme of hidden truths and the barriers between people. We are given a glimpse of the hardships associated with being a part of a troupe of itinerant actors. There’s no permanence to their occupation and hardly any semblance of normalcy in their personal lives. Like floating weeds, they drift from one place to the next, sometimes from one life to another ― drifting apart from the ones they love, with no roots to ground them. Always on the move, not knowing what tomorrow will bring.

6. Early Summer (1951)

Noriko (Setsuko Hara) is an unmarried 28-year-old office worker living with her extended family in suburban Tokyo. As the story unfolds, we’re introduced to her parents (Ichiro Sugai and Chieko Higashiyama), her older brother Koichi (Chishu Ryu) and his wife Fumiko (Kuniko Miyake), and their two young sons. Noriko’s boss suggests a potential marriage match for her with a wealthy 40-year-old businessman. This proposal catalyzes a series of discussions and conflicts within the family as they grapple with Noriko’s future and their own expectations. Noriko’s aunt Masa (Haruko Sugimura) becomes particularly invested in the matchmaking process, embodying traditional values and the pressure on women to marry. As the family debates Noriko’s prospects, we witness the subtle tensions and affections that bind them together.

The narrative takes an unexpected turn when Noriko decides to marry Kenkichi (Hiroshi Nihonyanagi), a widower with a young daughter and an old friend of her brother. This choice made independently and against her family’s wishes, sends ripples through their tightly-knit unit. Ozu’s static camera and carefully composed frames invite viewers to observe the characters’ interactions as if they were part of the household, fostering a deep connection with their joys and struggles. A recurring shot of a narrow path between the houses serves as a visual metaphor for life’s journey and the choices we make along the way. The potential move of Noriko’s parents, the growth of Koichi’s children, and Noriko’s impending marriage all speak to the inevitable changes that families face. Ozu finds beauty and poignancy in these transitions, suggesting that it’s through accepting change that we can appreciate the fleeting nature of life’s seasons.

5. Good Morning (1959)

A loose remake of Ozu’s silent “I Was Born, But…” (1932), “Good Morning” is a delightfully simple movie concerning the various shifting parent-kid dynamics within a family amidst the gradual encroachment of Western consumerism upon post-war Japanese culture. Through the lens of two young brothers’ quest for a television set, Ozu presents an unabashedly fun (yet meaningful) look at various primal modes of expression and communication ― whether through greetings, small talk, gossip, silent protest, or just silly flatulence humor. The film is set in a housing complex on the outskirts of Tokyo, where we follow the daily lives of several interconnected families.

At the center of the plot are the Hayashi brothers, Minoru (Koji Shitara) and Isamu (Masahiko Shimazu), whose stubborn desire for a TV set drives much of the plot. Their parents, Keitaro (Chishu Ryu) and Tamiko (Kuniko Miyake), resist the boys’ pleas, believing television to be a frivolous distraction. Frustrated by their parents’ refusal and inspired by their neighbor’s son Zen (Masahiro Kono), who practices English by repeating “I love you” to a portrait of Audrey Hepburn, the brothers decide to take a vow of silence. They refuse to speak to anyone, answering only with curt nods or shakes of the head, including their parents and teachers, to their great consternation.

Parallel to this central narrative, Ozu weaves in subplots involving the community’s adult residents, where a misunderstanding about unpaid dues for a women’s club leads to gossip and strained relationships between neighbors. Yuharu Atsuta’s cinematography is characterized by a warm, naturalistic light that complements the domestic setting. As a commentary on post-war Japan, the film remains a valuable and thought-provoking work, offering insights into the country’s evolving values and cultural identity.

4. Tokyo Twilight (1957)

Ozu’s final film, to be shot in black and white, is also one of his bleakest and most emotionally intense works. Set against the backdrop of a cold, wintry Tokyo, the narrative follows the Sugiyama family, primarily focusing on two sisters: the reserved and responsible Takako (Setsuko Hara) and the younger, troubled Akiko (Ineko Arima). Their father, Shukichi (Chishu Ryu), a widower and bank employee, serves as a steady but somewhat ineffectual presence in their lives. As the story unfolds, we learn that Takako has left her alcoholic husband and returned home with her young daughter, while Akiko grapples with an unplanned pregnancy and a fruitless search for her boyfriend, Kenji (Masami Taura).

The plot takes a dramatic turn when the sisters discover that their long-absent mother, Kisako (Isuzu Yamada), presumed dead, is alive and running a mahjong parlor. This revelation and the ones that follow in its wake profoundly affect Akiko, leading her into a downward spiral of despair and self-destruction. Her emotional turmoil leads her to make a series of increasingly desperate decisions, culminating in a tragic accident that serves as the film’s climactic moment. Ozu captures the cityscape of Tokyo in a state of flux, with sleek skyscrapers and neon lights juxtaposed against traditional temples and narrow alleys. This dovetails with the film’s thematic design as a meditation on the decline of traditional Japanese values and the rise of modernity. Shadows play a crucial role, often partially obscuring characters’ faces during moments of emotional intensity, suggesting the hidden depths of their pain and the difficulty of true communication.

3. An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

The last film made before his death, “An Autumn Afternoon,” displays all of Ozu’s characteristic subtlety and minimalist style in crafting a deeply moving tale that serves as a fitting capstone to a remarkable career. Shuhei Hirayama (Chishu Ryu) is a widower living with his daughter Michiko (Shima Iwashita) and his younger son Kazuo (Shinichiro Mikami). His older son Koichi (Keiji Sada) is married and living separately. The narrative progresses, driven by Hirayama’s growing realization that he must arrange a marriage for Michiko despite his reliance on her as a housekeeper and companion. Interwoven with this central strand are subplots involving Hirayama’s friends and colleagues. A chance encounter with his former teacher, nicknamed “The Gourd” (Eijiro Tono), catalyzes Hirayama’s decision. Seeing his once-respected mentor reduced to a drunk, dependent on his unmarried daughter, Hirayama recognizes the potential future he wants to avoid for Michiko.

As Hirayama grapples with the idea of Michiko’s marriage, he must also contend with his own feelings of loneliness and the challenges of aging. His evenings spent drinking with old school friends and war comrades highlight the comfort he finds in nostalgia and routine, even as the world around him changes rapidly. Ozu’s pillow shots in his final film take on added poignancy, often focusing on empty spaces or industrial landscapes that reflect the characters’ inner states and the modernization of Japan. The muted autumnal palette reinforces the film’s themes of change and the passing of time. Splashes of vibrant color – like the red of a teakettle or the bright packaging in a supermarket – stand out against the subdued backgrounds, highlighting the encroachment of modernity on traditional Japanese life.

2. Late Spring (1949)

“Late Spring” stands as a towering testament to Ozu’s genius in finding universal truths in the specific through its careful observation of a father and daughter navigating a critical transitional period in their lives. Noriko (Setsuko Hara) is a 27-year-old woman living contentedly with her widowed father, Professor Shukichi Somiya (Chishu Ryu). Their peaceful coexistence is disrupted when family and friends begin to pressure Noriko to marry, insisting that at her age, she should no longer be single. But Noriko resists these efforts, expressing her desire to remain with her father and care for him. Her aunt Masa (Haruko Sugimura) takes it upon herself to arrange a match for Noriko while Shukichi grapples with his own conflicting desires – wanting his daughter’s happiness but also relying on her companionship.

Things take a turn when Shukichi, realizing that his presence is an obstacle to Noriko’s marital prospects, decides to feign interest in remarrying. This white lie, designed to push Noriko towards accepting a marriage proposal, forms the emotional crux of the film. Believing her father will be cared for, Noriko finally agrees to marry. Ozu masterfully uses his “tatami shots” to create intimate observational perspectives, wherein the viewer is invited into the characters’ living spaces and allowed to feel like silent participants in their daily travails. Noriko’s reluctance to marry reflects a changing Japan, where traditional values clash with emerging notions of personal fulfillment. The film’s ending, marked by a sense of resignation and acceptance, is both heartbreaking and profoundly moving.

1. Tokyo Story (1953)

“Isn’t life disappointing?”

Widely regarded as Ozu’s magnum opus and voted the greatest film of all time in Sight and Sound’s 2012 poll, “Tokyo Story” is a deeply moving tale about the complexities of aging and maintaining familial bonds within a rapidly urbanizing landscape. It follows the old couple Shukichi (Chishu Ryu) and Tomi Hirayama (Chieko Higashiyama) as they journey from their rural home in Onomichi to Tokyo to visit their adult children. Their arrival in the bustling capital sets in motion a series of encounters that reveal subtle fractures in their family relationships. Their eldest son, Koichi (So Yamamura), and their daughter, Shige (Haruko Sugimura), greet their parents with a mix of obligation and mild inconvenience. Both seem too preoccupied with their own lives to spend much time with their parents anymore.

In contrast, it is their widowed daughter-in-law, Noriko (Setsuko Hara), who shows genuine warmth and care towards the old couple. The children shuttle their parents between themselves, even sending them to a noisy, hot spring resort to alleviate the burden of hosting them. But when Tomi falls seriously ill, and the children gather at her bedside, their reactions to her passing brutally make explicit the true nature of their relationships. In the aftermath, it’s Noriko who again demonstrates the sincerest grief and compassion. Through her, Ozu suggests that true family bonds transcend mere blood relations.

Ozu’s use of repetition and mirroring throughout the film adds layers of meaning to seemingly simple scenes. The parents’ arrival in Tokyo is echoed in their return to Onomichi, highlighting the cyclical nature of life and the inevitable changes that occur even over a short period. The film majestically captures the growing distance between generations as adult children become absorbed in their own lives at the expense of their relationships with their parents.