Unicorns have, for centuries, been fabled symbols of the most distilled essence of majesty, purity, and nobility; to kill or even think of harming one would be tantamount to the most feral demonstration of humanity’s soul-blackening capacity for corruption and the destruction of all things good. So pure is the unicorn that, given the unfailing demonstrations of decay and greed that populate our daily screen time, it’s a wonder such atrocities against the mythic beast have yet to be used as a symbol in one of the most increasingly ubiquitous sub-genres of the past few years: the smug “eat the rich” satire.

That all changes today, as debuting writer-director Alex Scharfman brings the death of the unicorn into that very thematic arena with, fittingly enough, “Death of a Unicorn.” From the title, one would reasonably surmise that Scharfman may be exploring this avenue by way of a mythic fantasy period piece or, otherwise, may very well be using such a title metaphorically. Guess again, for “Death of a Unicorn” transplants its very literal namesake into the modern day to see precisely how the current era of late-stage capitalism would respond to such purity. Take a wild guess as to how that goes—odds are, you’re right.

Our conduit into this world—and the film’s most concentrated (read: half-conceived) focus on its corruptibility commentary—is Elliot Kintner (Paul Rudd, leveraging his likable everyman quality for whatever subversion his stiff writing will permit), a lawyer working for a pharmaceutical company. Looking to get into his terminally ill boss’s (Richard E. Grant) good graces, Elliot accepts an invitation for a weekend at the man’s remote boreal estate. With a great deal of emphasis on family, the Big Pharma magnate Odell Leopold insists that Elliott bring along his estranged daughter Ridley (Jenna Ortega), touched by the family’s pre-narrative story of the loss of their matriarch.

Along the way, Elliott and Ridley hit a snag. And by snag, I of course mean a unicorn. Just as puzzled by what the hell they’re looking at as what the hell they’re supposed to do with it, Elliot loads up (what they think to be) the corpse of the mythic creature and continues on to their weekend engagement. Of course, when Odell and his own ambitious family (Téa Leoni and Will Poulter) catch wind of this carcass and its seeming potential to cure the incurable, all decorum falls to the wayside in favor of syringes and test tubes, despite the dangers of what may be lurking out in the woods, holding equal interest in this fallen creature.

Class commentaries aren’t anything new, but it seems as if there has been a particular recent concentration on acidic portrayals of the 1% and the gleeful infliction of pain under the banner of comeuppance. (Why this has become a particular point of interest in today’s political climate, I’m sure I couldn’t say…) “Death of a Unicorn” thus comes at a moment that is, somehow, both opportune and outdated. The influx of such features has, simply put, reached such a fever-pitch in the wake of films like Ruben Östlund’s “Triangle of Sadness,” Rian Johnson’s “Knives Out” series, and Bong Joon-ho’s… well, anything, that the moment of heightened transmission for public interest seems to have died down significantly, even if the trajectory of the 1%’s riches continue to move in the opposite direction.

Had A24 released this film at the tail-end of 2022, then it may as well have been retitled “Death of a Satire,” but Scharfman’s film, even distanced from the moment of diminishing returns, still finds itself failing to justify its commentary outside its elevator pitch. Say what you will about Östlund and Johnson—call them smug, call them out-of-touch, call them to the dinner table as you serve their class cohorts—at least they knew that their comedic commentaries would benefit from some actual, you know, comedy. “Death of a Unicorn” is just as blunt with Poulter’s half-baked one-liners as it is with its satirical dialogue, but none of it ever elicits more than an occasional mild smirk.

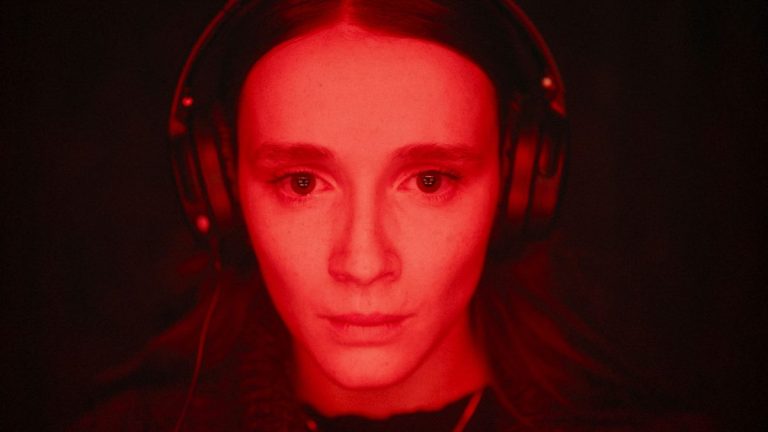

As the film then transitions to the point of isolated horror, Scharfman fails to match the increasingly rote violence—how often can someone press themselves up against a wall before being “unsuspectingly” gored by a unicorn horn?—with a reason to care, particularly insofar as Rudd’s and Ortega’s dynamic is concerned. That Ridley is such a Gen-Z typecaster’s wet dream—She vapes! She has a septum piercing! She waxes poetic about how philanthropy is just a camouflage for the oligarchy!—is only half the problem, but whatever development the director is attempting to achieve through Elliot’s unconvincing flip-flopping only reinforces the strength, or lack thereof, of his motivation in adding another point to an argument that’s already passed him by.

“Death of a Unicorn” announces in its title an impending post-mortem, but Alex Scharfman’s dull scalpel ensures that his film is more likely to be a symptom of our modern social downturn than anything resembling its cure.