Black Rabbit, White Rabbit (2025) continues Shahram Mokri’s experiments with distinctive cinematic techniques and his pursuit of a new form achieved through the extreme application of those techniques. As the first Iranian to watch “Black Rabbit, White Rabbit,” produced by Negar Eskandarfar, at its premiere screening at the Busan International Film Festival in South Korea, I quickly recognized the recurrence of Mokri’s formal language in this film: the use of long takes without cuts and carefully selected edits determined by the director, irrespective of conventional rules regarding narrative rhythm.

“What makes Mokri’s film so open to analysis is its precise emphasis on cinematography and editing, an emphasis made possible by the deliberate restraint shown in the screenplay, mise-en-scène, and performances. It is best to approach this film by acknowledging that if we were merely to read the script, observe the staging, or watch the actors perform their roles, we would never come close to the experience of seeing the film projected on screen. This is distinctly an auteur aspect of independent cinema.

What makes Mokri’s films remarkable and worth watching is neither the use of well-known actors nor unattainable set designs and extravagant budgets. Rather, it is his use of a personal cinematic language to articulate the concerns and themes of the screenplay—an achievement that, in practice, amounts to reaching “form.” Many will undoubtedly say that “Black Rabbit, White Rabbit” is simply “Fish & Cat” or “Invasion” revisited, since all speak of a circular world accompanied by a prolonged camera movement through a mental labyrinth. Yet a key point about this filmmaker is often overlooked: he possesses a cinematic language uniquely his own and has followed this path from the very beginning.

In his 1965 essay “Cinema of Poetry,” the great Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini argues that the difference between a director and a poet lies in the fact that a poet has access to a pre-existing dictionary of language and creates a world through words, whereas a filmmaker constructs his own dictionary for each film and uses it to compose his poem. In Mokri’s case, one could argue that, in line with the auteur approach in cinema, he created his dictionary in “Fish & Cat” and has since placed various subjects and stories within that linguistic framework. Just as most filmmakers employ the established language of découpage and mise-en-scène, Mokri utilizes his own distinctive style of both.

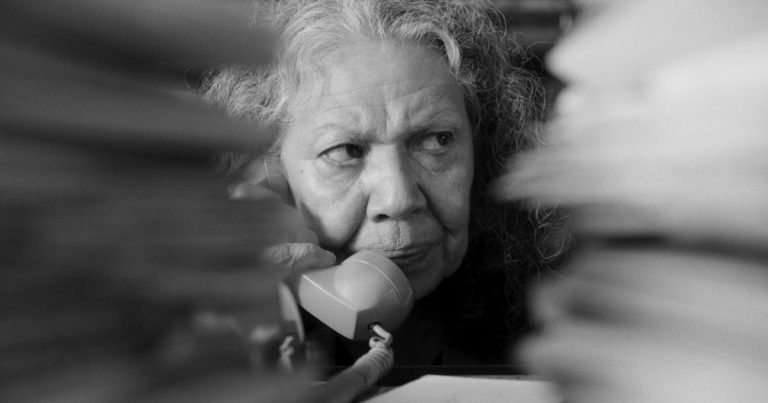

The film opens with a woman completely wrapped in bandages. The camera accompanies her, and the uninterrupted shot generates an exciting suspense for the viewer: can I guess where the cut will occur? Or is the filmmaker one step ahead, attempting to read my mind? This mental game replaces traditional dramatic progression.

The use of long takes functions as a form of ‘dead time’ in the film, a concept closely associated with the cinema of Wim Wenders. Yet the issue here is that this dead time neither reveals character in depth nor offers the immersive engagement with nature or environment that one finds in Wenders’ films. This shortcoming occasionally severs our connection with the protagonist and her situation, producing a distancing effect—one that transforms us into patient spectators waiting for the next cut. Here, the deliberateness of the director’s visual and narrative cuts becomes fully apparent. The result of this intentional manipulation is the dissolution of the audience’s organic connection to the film’s dramatic flow.

However, this is not necessarily a flaw. By experimenting with this style across several films, Mokri has reached a new approach that contains a kind of synthesis. One could say that this distinct technique generates a different and unpredictable experience for the viewer. From its very first image, the film conveys the sensation of a cocoon and a movement toward liberation from it—a birth seems imminent. As the film progresses, we realize this hypothesis was correct: many births are on the horizon.

If we consider the work as surrealist—where the fusion of two opposing elements produces an inseparable whole—we can identify several dualities: the bandaged covering of the film’s central woman (Hasti Maali) as cocoon and its removal; the magician’s hat and the rabbit that leaps from it; and most importantly, the face veil of women, whose removal suggests the emergence of a new current in Iran’s social life.

In this sense, “Black Rabbit, White Rabbit” may be read as the filmmaker’s manifesto against the establishment of a patriarchal society, and as an expression of the powerful countercurrent unfolding today. These motifs, all pointing toward birth, ultimately guide the mind toward the abstract concept of freedom—achieved through the removal of masks. As revealed to the Tajik girl who aspires to become an actress: to become an actor, you must first recognize your inner mask.

In the end, what lingers from ‘Black Rabbit, White Rabbit’ is a journey through the intricate layers of an adventurous mind—shaped by its social moment, yet bold enough to carve a new design and inscribe its contemporary imagination into cinema’s history.

![Hereditary [2018]: An Unsettling Family Drama that will leave you Cold!](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Herediatry_HOF-768x421.png)

![Soul [2020] ‘NYAFF’ Review – An Atmospheric Horror about Isolation](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Soul-Movie-Review-highonfilms-1-768x405.png)