After 2024’s “Article 370,” the team of two Adityas and Monal Thakkar is back with another smartly-crafted, shiny Trojan horse that hides, albeit clumsily, an outrageously terrifying political statement regarding their favorite topic, Kashmir. “Baramulla” begins as a Nordic noir–tinged thriller about a PTSD-stricken detective investigating the disappearance of children in the valley, but soon drifts into the eerie realm of the supernatural.

Strictly from a narrative perspective, the Aditya Suhas Jambhale directorial does blend the supernatural with the police procedural well. However, the real horror is how Jambhale, who co-wrote the script with Aditya Dhar and Thakkar, manipulates the storytelling platform that is provided by our beloved artistic medium – Cinema.

Let us face it. Jambhale, Dhar, and Thakkar form a different breed, establishing themselves in a separate bracket from the likes of Vivek Agnihotris and Sudipto Sens. The narrative filmmaking capability of Jambhale exceeds that of other Bollywood filmmakers who have found the easy way to stay relevant.

Exalt the sitting government’s work and vilify Indian Muslims. Their films resemble the work of a zombie, swinging wildly and frenetically with hatred foaming at the mouth. Jambhale’s work is different. He understands the power of cinema. His propaganda whittles to excavate a beautiful-looking statue that will attack the audience with a sledgehammer when the opportune time comes.

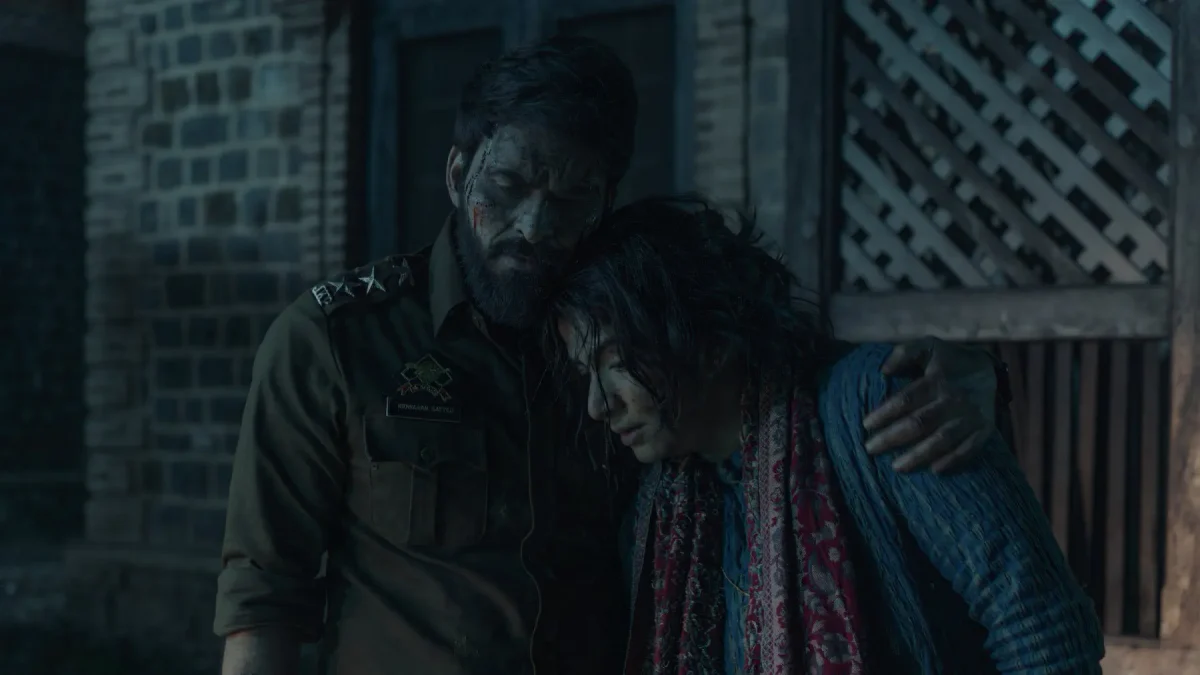

As mentioned earlier, “Baramulla” has the appearance of a fairly engaging mystery thriller. It starts well with the eerie disappearance of a young boy while volunteering for a vanishing trick of a local magician. The story does not hide its inclination towards the supernatural. Amidst the tumultuous unrest created by the local separatist militants, enter a good Muslim cop to find the missing child. DSP Ridwaan Sayyed (Manav Kaul), who has his own internal hatchet to bury, takes the job and shifts to Baramulla with his family. Of course, the good Muslims are all pro-establishment.

Also Read: The 10 Criminally Underrated Movies on Netflix

As Sayyed and his officers continue the investigation, which unsurprisingly points towards Kashmiri militants kidnapping the children to radicalize them in Islamic holy war (jihad), his household mysteries run in parallel. Sayyed’s daughter, Noorie, is plagued by the phantom smell of a dog, while no dog can be seen in the vicinity. His young son, Ayaan, befriends a young ghost. Sayyed’s wife, Gulnaar, experiences various paranormal disturbances. Jambhale uses the horror tropes well.

The influences of modern horror greats (like Mike Flanagan’s “The Haunting of Hill House” and Scott Derrickson’s “The Black Phone”) can be observed. Despite its ill intentions, one has to commend the way the script converges Sayyed’s investigation with the supernatural experiences of his house, with the climactic twist serving as a double-edged knife. Story-wise, the twist perfectly rounds the mystery, while acting as a vehemently manipulative piece for the film’s propagandist nature.

It is not to say religious fanaticism is ghostly non-existent. However, using the past to paint an entire group of people under the same brush of plausibility is a grave sin. Having said that, as a filmmaking piece, “Baramulla” is worryingly convincing in its vision. Jambhale’s astute direction is accentuated by the craftiness of cinematographer Arnold Fernandes’ camera.

No amount of hatred can sway the heart of a person with a camera when it comes to capturing Kashmir. And this reflects. Despite the condemnation the film reserves for its residents, Kashmir provides the stunning visual backdrop for some eerie treats. The disappearance scene of the fisherwoman’s boy is one such example. A solid cast led by the dependable Manav Kaul helps too.

In my review of “Article 370,” I termed the film a sophisticated version of “War Rukwa Di Papa.” “Baramulla” is not an exact propaganda pamphlet of the current ruling party of India, like “Article 370” was. However, it is an extension of the same ugly, hateful spirit that “Article 370” channeled. The story does not take much time to argue for the violation of human rights via the glorification of the use of pellet guns.

Even the concept of civil unrest is vehemently vilified, let alone considering spending a minuscule amount of effort to understand. As a matter of fact, “Baramulla” poses an even bigger threat to the secular fabric than “Article 370” did, especially because it propagates an advocacy of alienation of Kashmiris, which is not dependent on any particular political party. Hegemonic changes come and go, disproportionate feelings of vindictiveness remain, fueled by artistic work as this.

![Gunpowder Milkshake [2021] Review – A colorful albeit forgettable blast of feminist entertainment](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Gunpowder-Milkshake-3-768x433.jpg)