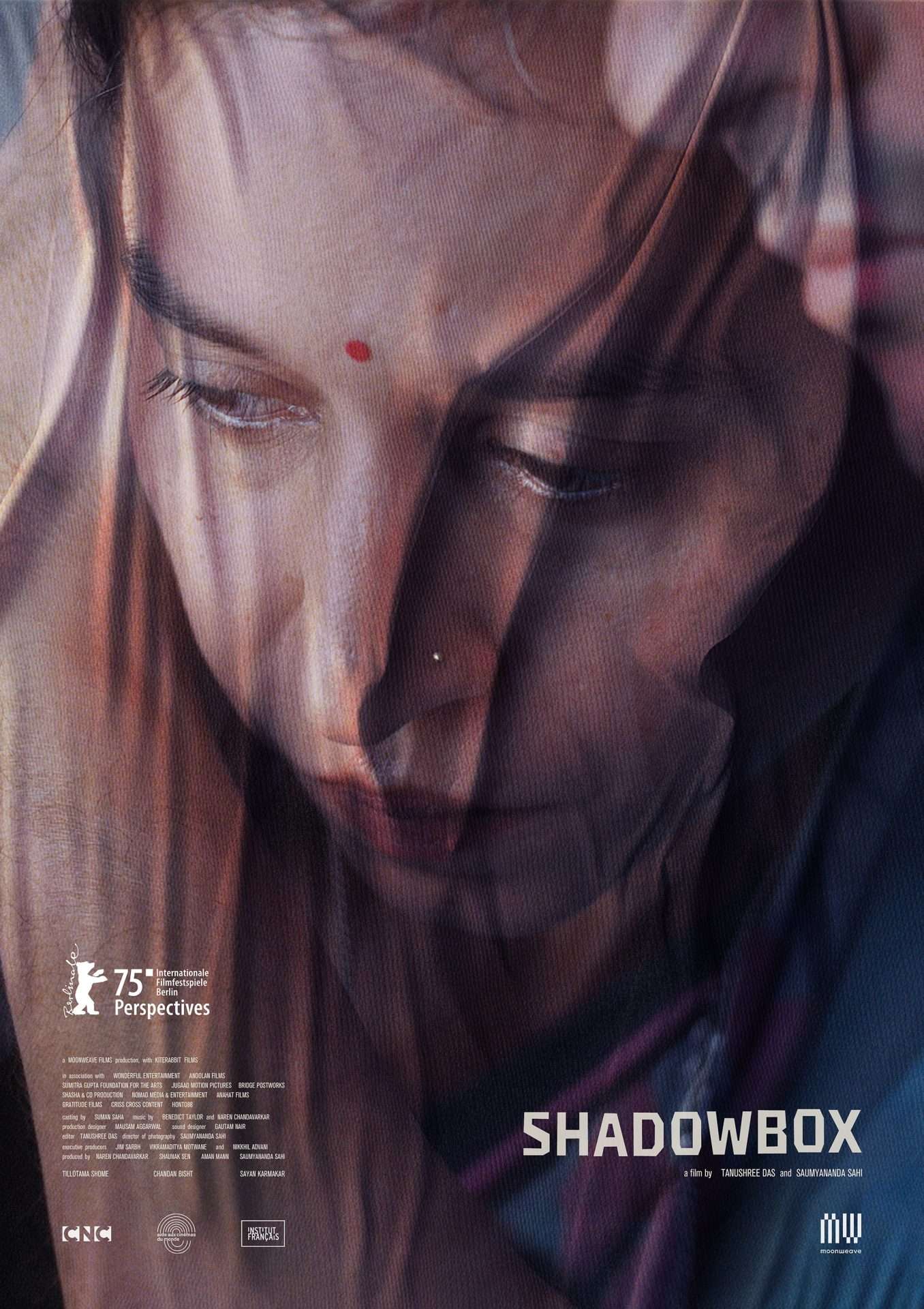

“Shadowbox” (“Baksho Bondi”) is a film that lingers in the quiet spaces of grief, masculinity, and resilience. The film follows Maya, a woman navigating the weight of love and loss, bound to a man—Sundar—who carries the invisible wounds of his past. Set against a landscape where personal battles mirror larger societal fractures. “Shadowbox” had its world premiere at the 75th Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale 2025) this year, in the newly introduced ‘Perspectives’ section, which celebrates debut voices in cinema. Co-directed by Tanushree Das and Saumyananda Sahi, “Shadowbox” reflects their backgrounds in documentaries, blending realism with poetic storytelling. Their collaboration with Shome, whose performance anchors the film’s emotional weight, brings depth to its exploration of trauma and care.

Shubham Sharma from High On Films had the opportunity to engage in a conversation with the filmmakers and actors. To explore the film’s deeply intimate yet political gaze, refusing to explain itself yet demanding to be felt. As we delve into their creative process, themes of authorship, collaboration, and personal truths emerge, shaping a film that doesn’t just tell a story but listens, to its characters, its audience, and the world around it.

Shubham: How does it feel to present a film that is so deeply rooted in a national or local context to an international audience? How was the reception, and how do you feel about it?

Saumyananda: Just yesterday, someone from East Berlin shared how they connected with the film, relating it to their own childhood experiences. That was incredibly moving for us because it reinforced how, despite being a deeply local and rooted story, the film resonates on a universal level. Watching it with an audience in Berlin and hearing them laugh, react, and engage with it in real time was a truly special experience.

Shubham: The next thing I wanted to ask is a broader question. Watching the film, there are so many layers—gender roles, particularly patriarchy, the migration of people to Kolkata and how they are treated, and the dynamics of the family itself, especially their exclusion. As the story unfolds, it grows into something much larger and more visceral. Social exclusion seems to be a recurring theme in the backdrop, shaping everything that happens in the film. While it’s not always explicitly stated, it feels deeply ingrained in the story.

So, I wanted to ask—what was your idea behind portraying social exclusion? How do you feel about the way it affects people, especially in today’s world?

Tanushree: When we were writing the film, we had the story of her parents. How they married outside their community and faced intense stigma from their relatives because of it. That was one layer. But we were also thinking about mental distress and other forms of social alienation.

For me, this theme is very personal. Growing up, I was always observing the way adults interacted, and I found it striking how quick people were to judge before they were willing to see, to feel, to understand. And it’s not just on a large scale—issues of gender, race, or sexuality. It happens at a microscopic level too.

For example, in many families, it’s just accepted that a “good family girl” will have an arranged marriage. If she falls in love with someone, that’s already enough of a disruption. But if he’s from outside the community, that’s even worse. And then, if he comes back with mental distress or struggles, instead of offering support, people turn away. They don’t empathize; they just say, Didn’t I tell you?—as if they were just waiting for things to go wrong. Instead of feeling for a person, they use their suffering as proof of their own assumptions.

For me, that was the catalyst for the story. So much would be different if we simply allowed ourselves to feel for the person standing next to us, instead of immediately resorting to judgment. That’s what we wanted to explore with this film.

Shubham: Along those lines, I wanted to ask about your performance—which was incredible. But so much of it wasn’t about what was being said, but rather about what remained unsaid. So much of the performance seemed to be about what was going on in your character’s head.

When working with a script, you typically have dialogue and direction to shape a performance, but silence isn’t something that can be explicitly written. How did you approach that? How did your relationship with the script evolve, and how did you prepare for this role?

Shome: A performance like this was only possible because of the generosity of the directors in sharing various drafts of the script over the six years since we first met. From the very first draft I read, the one that made me fall in love with them and the world of the film, many more versions emerged over time. Each draft was an attempt to understand the family, and each continued to exert a certain force, even as time passed.

During the shoot, I would sometimes wake up in a panic, thinking we had forgotten to shoot a scene, only to realize that the scene wasn’t in this version of the script. That process of living with the script over the years helped immensely in embodying the role.

One of the greatest gifts of the script was that it didn’t dictate the exteriority of the character. It didn’t say, Maya’s face crumbles. Maya now cries. Maya smiles apprehensively. None of the usual directions telling an actor how to perform emotions were there. Because the film itself wasn’t about performing emotions. So, there was no exteriority for the character besides her labor—her daily chores, her business. Because of that, I never felt obligated to “hit marks” or deliver a specific kind of performance.

So what was left to do? Just be there. The space, the architecture of the room, and the environment of the scenes became my co-actors. Some of the sequences were so documentary-like that I was acting alongside the real world. The railway station, for example, became an essential co-actor in its own right. That experience was incredibly freeing.

The absence of externalized emotion allowed the interiority of the character to breathe. It wasn’t something I had to consciously manufacture—it was born from the years of living with these drafts, from stepping into the space, from understanding the reality of Maya’s life.

And then, of course, there were personal resonances. I drew from my own life, from experiences of caregiving, and from things I had come to understand deeply over the past few years. All of that helped shape the performance, in ways that didn’t need to be explicitly shown, just lived.

Shubham: One thing I noticed after watching the film and going through the credits was how many independent filmmakers I recognized. People I’ve been following over the years. Showing up as producers, in the special thanks, or in some other way.

As a filmmaker myself, that felt incredibly heartwarming. Just from looking at the credits, I could sense a real community coming together. People figuring out how to make this film happen, and how to support each other and the story. So, I wanted to ask about your experience working with so many different voices.

Shome: Before answering, I just want to say that they have a lot of love. People really love them a lot. They represent something rare. Their emotional maturity, their ethics, and their standards stand out. I think, in a way, everyone wants to feel a little bit holier just by associating with them. So, yes, there’s definitely an element of let’s stand next to them—it makes us look good, whether they accept it or not.

But beyond that, this group of people who came together for the film already knew of each other, we just hadn’t found common ground before. And they became that common ground.

Okay, now they can answer your question.

Saumyananda: We are cinematographers and editors, both before and after this film. So, the support really started with people we had worked with before. For example, Shaunak Sen, who directed “All That Breathes.” I was a cinematographer on that. Naren was the primary producer. I’ve known him since school, and we had also collaborated on another film where I was both DP and editor.

Then, there were producers like Vikramaditya Motwane and Prashant Nair, who are directors I’ve worked with as a cinematographer. Through the time we spent together, they got to know about the work we were doing on this film, and that’s how they came on board. But from there, it snowballed—they would call their friends, and their friends would join as well.

It was a model born out of necessity. In India’s current landscape, raising funds for a film like this, without government support and with an uncertain distribution future, is incredibly risky. Naren had this idea to spread that risk across multiple people.

He often talks about his father, who was an architect. His father believed it was important to take on projects that gave back to the community—not just the ones that paid the bills, but those that fulfilled a broader sense of responsibility. That idea shaped how we built this film. So, this community that formed wasn’t just made up of financiers and producers. It became a support system. People backing each other and the idea behind the film.

Shome: Too good to be true, no?

Shubham: Honestly, being based in Berlin as a filmmaker, I often see the complete opposite. The industry here can feel so individualistic. It’s rare to meet the person before their ego.

Shome: It’s the world’s story. That’s why what they’ve built stands out so much. That’s why I prefaced this question with “who they are.”

Tanushree: All the more reason why we have to do this. We have to let go of our egos—sometimes even forget about them entirely. And if ego is present, we have to find other ways to navigate it. For me, what works is love. I truly believe in giving—whatever I have, however small. As an editor, I’ve always given my best, and many times, I didn’t receive anything in return. People often forget. But then, sometimes, it comes back in unexpected ways, and I realize—oh, I wasn’t forgotten after all.

I think often, from where we stand, we feel alone. But sometimes, it’s just a matter of reaching out.

Saumyananda: We also wanted to build a model where every producer came in on equal footing and with shared stakes. Our goal was to create something fair and equitable so that no single person held disproportionate power. So, no hierarchy. Of course, even without a hierarchy, different people played different roles. But it was never top-down. It was a lateral decision-making process.

Shubham: I wanted to ask about Debu’s relationship with dance. Amidst everything happening, especially in the ending, it stands out. I’d love to know more about where that came from.

Tanushree: My brother is a fantastic dancer. Though he doesn’t dance anymore. He really should. He’s a corporate lawyer now, taking care of the family, the next Maya in the making in many ways.

But for us, as kids, dancing—especially this particular kind of dancing—was something special. We were drawn to rap and dance without even knowing what they truly represented. We didn’t realize then that they were expressions of rebellion. But we felt it. We connected with it emotionally, naturally.

So, in a way, Debu’s dance is a statement. I can still move my limbs, even at 44. It’s about freedom. And, of course, when you watch someone like Pina Bausch say, dance, dance, or all is lost, you understand exactly what she means. Dance, music; the free flow of energy in the body, it’s all about survival.

For Debu, who is a silent observer, placed in this world without a choice, dance becomes his way of expressing himself. It’s his rebellion, his coming-of-age. That’s why he chooses Bangladeshi music, and Assamese music, not just Bengali. Politically, we stretch a little beyond the borders, left and right. Because in music and dance, there are no boundaries. There’s no limit to what you can feel and understand.

Saumyananda: Personally, I’m not a good dancer, and I’ve always been jealous of those who are. Somehow, I feel like people who can dance handle life better. That’s why it was important to give that to Debu. Because despite all the responsibility he carries, watching him dance makes me believe he’ll be okay.

Shubham: I think you touched on this, but I wanted to ask specifically about PTSD. The diagnosis was originally coined for soldiers returning from war, though in a different context. While watching the film, I felt that Sundar isn’t just suffering from what he has been through in the past, but also from the pressures of masculinity. He struggles to maintain respect in the eyes of others, especially his son. And yet, he’s failing to recognize this internal conflict.

How did you research that? And how did you approach portraying it in a way that feels truthful?

Saumyananda: I’ve been working on films about trauma for many years, including a documentary. And PTSD doesn’t necessarily have to come from war. It can come from other forms of trauma.

Tanushree: In Sundar’s case, it could even be the trauma of extreme masculinity itself. The rigid structures he was part of, the expectations placed on him, and the ways those expectations broke him—that in itself is enough to cause PTSD.

Saumyananda: We discussed many different possibilities for what could have caused Sundar’s mental distress, but we didn’t want to presume to know. We wanted to leave it open-ended. And then, after casting Chandan, something unexpected happened. He comes from a village where many of his relatives have joined the army. After he got the role, he shared a story that was eerily similar to Sundar’s, a man who had been dishonorably discharged and became a laughingstock in his community. He told us, “Arey, yeh toh aapne likha sahi hai. Yeh toh humare gaon me aisa hota hai.” It was almost telepathic, the way our writing and his real-life experiences aligned.

He brought a lot to the role because he understood that world firsthand. But for us, our approach has always been rooted in lived experience. We’re documentary filmmakers at heart, and we don’t assume we fully understand something. In an attempt to understand it, that’s the journey. That’s why we write so many drafts. The research doesn’t end. It’s a continuous process.

Shubham: I wanted to ask about the dynamic between you and Sundar. It seems like everyone around you is unsure why you’re together. Why did you choose to stay? Given everything Sundar has been through, everything you are going through, and even what your son is experiencing, how do you make sense of this?

Maybe, in the script, there are so many reasons that I or anyone else could imagine. But for you, how do you figure it out? How do you still feel that there is love, that this is worth exploring when everything around you tells you otherwise?

Shome: I think the simplest way I made peace with it was this: It is nobody’s business. My family, my rules. I don’t owe anyone an explanation for why I love Sundar, why I love my son, why I stay. I don’t need to justify it. That clarity helped me. And I think that’s something that comes with time—with getting older.

Society always wants explanations. Why did you marry outside your class? Why did you fall in love with this person? Why do you stay? But sometimes rejection, and criticism—being pushed out—makes you see yourself more clearly. When the world refuses to accept you, you’re forced to accept yourself, even more brilliantly. Until then, your sense of self is just an idea. But when you’re cast out and you survive that, when you own your choices despite it, that’s when you really know who you are.

That’s how I saw Maya. She doesn’t owe anyone an explanation. She knows the weight of her decision. She knows how hard it is. She knows there will be days when she won’t be able to manage it all, when everything will fall apart, and then she’ll build it up again. And if someone understands that, wonderful. If they don’t, that’s okay too.

I felt this come together in a very real way at the railway station scene. At that moment, Maya hears the news—the police have found Sundar’s body. And I was surrounded not by actors, but by real people from that place. Strangers. And yet, the way they looked at me… I felt understood. There was no crew, no setup, just the camera, me, and the people around us.

They could have asked me why I was crying. They could have intervened. But they didn’t. They gave me my space. And that’s what broke me in that moment; not just the grief of the character, but the generosity of the people around me. I remember seeing a tea seller watching me. He didn’t know what was happening. He didn’t know I was acting. But in his body language, I could see concern. He wanted to help, but he also understood. Understood that sometimes, what a person needs most is space.

That’s what the film was for me. That moment, that unspoken recognition. We don’t need to understand each other’s specifics, each other’s struggles. But when we see someone breaking, we recognize it. We see ourselves in it. And sometimes, that’s enough. That’s more than enough. The generosity of humanity.

Shubham: That reminded me of the poem “Hatasha” by Vinod Kumar Shukla. “Mai us vyakti ko nahi jaanta tha, par hatasha ko jaanta tha”

Tanushree: Waah!

Shubham: I will end the interview with this, how has your experience been at this year’s Berlinale?

Shome: It feels like something significant is unfolding at the festival, though I can’t quite articulate it fully yet. It’s more of a gut feeling—like this particular edition, under Trisha’s leadership and the programming team’s vision, is a direct response to a certain crisis. And being here, I feel like we’re part of something historic.

Common threads are running through the films I’ve seen—like “Living the Land.” The first thing that struck me was how, despite being from completely different worlds, China and India, the director’s gaze carried a striking similarity. There’s something about the way women are framed, the way their bodies are looked at, the way the impact of violence is rendered. It feels like the programmers and curators of this festival understand something crucial.

There’s a kind of fatigue that comes with attending predominantly white, European festivals, where the same patterns of misogyny in programming persist. Festivals are meant to be safe spaces. Places we pilgrimage to. When that safe space fails, it’s exhausting. But here, that pattern seems to be deliberately broken. There is an intentionality in how we are being encouraged to meet, to talk, to connect. It’s not just a gathering, it’s a call to engage with one another. And it’s clear that women are listening. Really listening.

Tanushree: And the sensitive men. The really sensitive men.

Shome: This intentionality is also deeply relevant to the film. I often worry about the ways grief is written. How personal pain can sometimes come across as either too distant, too shielded, or, on the other end, overly sentimental, almost cloying. There’s a fine balance. When telling stories of grief and anger, if we build too much of a wall, even the most important truths can become inaccessible. The audience won’t hear it. And I think this festival, in its curation, is ensuring that doesn’t happen—that we are heard.