When Catherine O’Hara passed away on January 30, 2026, at the age of 71, the response was immediate and strangely intimate. This was not the kind of grief reserved only for icons with monolithic stardom. It was quieter, more personal, spread across generations who all seemed to feel the same thing: she was part of my life too.

That reaction says more about O’Hara’s place in popular culture than any award tally ever could. Her career didn’t follow a straight line of ascent and decline. Instead, it expanded outward, accumulating meaning over decades, crossing mediums, formats, and audiences. By the end, she didn’t belong to one era of film or television. She belonged to all of them.

The SCTV Years and the First Generation That Claimed Her

For Gen X audiences, Catherine O’Hara’s roots lie in SCTV, a show that treated comedy as both experiment and discipline. This was not star-making television in the traditional sense. It was a proving ground. O’Hara emerged from it not as a personality, but as a performer with uncanny control over character, rhythm, and tone.

Her work on SCTV established something essential about her approach. She didn’t chase laughs; she built people. Even in sketches, her characters felt psychologically complete, sometimes absurd, sometimes unsettling, often tinged with sadness. For those who watched her during this period, O’Hara represents a time when comedy trusted intelligence and craft. That sense of early discovery explains why this generation often speaks of her with a proprietary affection.

The Millennial Imprint: Home Alone, Beetlejuice, and Rewatch Culture

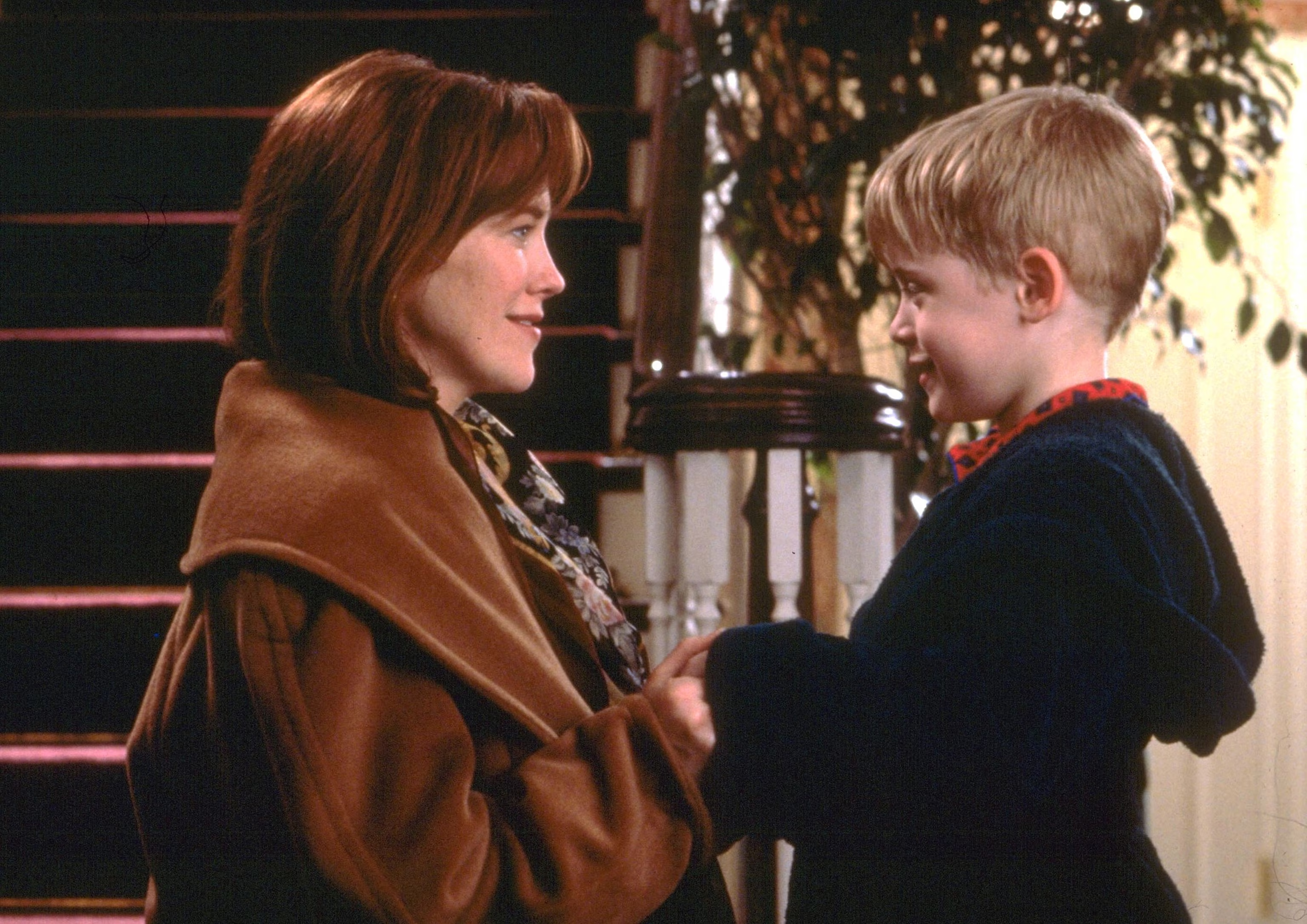

Millennials encountered Catherine O’Hara differently. She wasn’t a discovery so much as a constant presence. Home Alone played endlessly on television, becoming ritual rather than event. As Kevin McCallister’s mother, O’Hara brought urgency and emotional clarity to a film built on heightened chaos. Her performance anchored the fantasy, making the story feel human enough to revisit year after year.

Then there was Beetlejuice, where she revealed her willingness to go grotesque, theatrical, and fearless. Taken together, these roles placed her inside the collective memory of a generation raised on cable television and repeat viewings. She became part of the emotional furniture of childhood, someone audiences didn’t analyze at the time, but deeply internalized.

Not a Comeback, a Culmination: Schitt’s Creek and Moira Rose

When Schitt’s Creek arrived decades later, it was widely framed as a comeback. In retrospect, it reads more like a culmination. Moira Rose is not a reinvention so much as a synthesis of everything O’Hara had mastered: vocal control, physical precision, emotional sincerity, and a profound respect for character.

Moira could easily have collapsed into parody. Instead, O’Hara infused her with vulnerability beneath the camp, dignity beneath the excess. The performance recontextualized her entire career, prompting critics and audiences alike to look backward and recognize a throughline that had always been there. The awards mattered, but the cultural reassessment mattered more.

Gen Z and the Algorithmic Afterlife

For Gen Z, Catherine O’Hara’s work arrived largely through fragments. Short clips, reaction videos, and endlessly shared Moira Rose moments circulated across platforms. Detached from narrative context, what remained was pure performance. That is where O’Hara thrived.

Her appeal to younger audiences lay in her intentionality. Every sound, every gesture, every pause was deliberate. In an era fascinated by performance as identity, her work felt both theatrical and authentic. She wasn’t rediscovered because of nostalgia, but because her craft translated effortlessly into the language of the algorithm.

The Catherine O’Hara Effect

What ties these generations together is what can only be described as the Catherine O’Hara Effect. She disappeared into characters without erasing herself. She resisted trend-chasing while remaining relevant. Most importantly, she treated comedy as acting, not branding.

Each era encountered her at a different point, yet each felt she belonged to them. That is rare. It suggests not adaptability alone, but integrity of approach.

Catherine O’Hara’s death closes a life, but it does not close her presence. Her performances do not feel fixed in time because they were never built on contemporary shorthand. They were built on observation, empathy, and technique.

Some actors age. Some endure. A very small number become permanent. Catherine O’Hara belongs to that last group, not because she avoided change, but because she understood something fundamental about screen performance: if you play people honestly, they will outlive you.