With a denotative understanding of the idea that revenge is a dish best served cold, Hans Petter Moland’s gelid crime noir “In Order of Disappearance” (2014) opens with a chilling visual of snow-covered mountains and icy roads, a desolate locale where the landscape itself feels as hostile and unforgiving as the path its protagonist, Nils (Stellan Skarsgård), is about to undertake. The wintry setting of Norway serves as much of a character as the ruthless criminals who inhabit it while also serving as a stark reminder of the isolation and emptiness that accompanies the futile path of revenge.

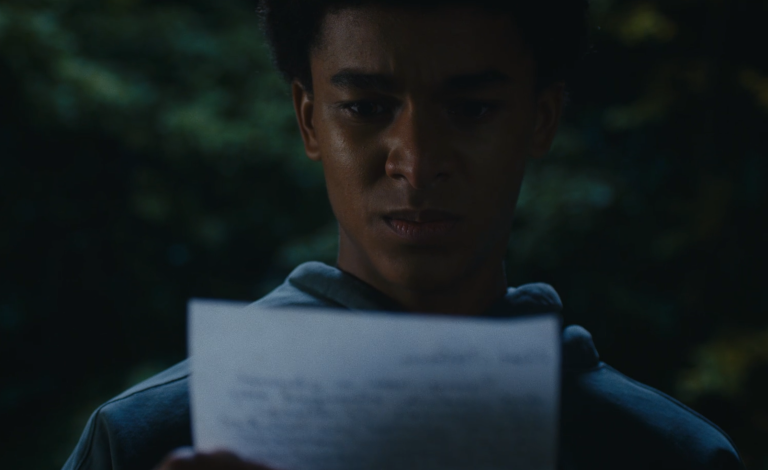

The film’s first act unfolds with a sense of tragic inevitability. A snowplow driver by trade, Nils leads a peaceful existence in a remote village. But when his wife receives an innocuous phone call, everything falls apart. His son, Erik, has been found dead from what appears to be a drug overdose, and the authorities, with the same efficiency of a snow plow clearing a highway, quickly label it an accident. But Nils, a man of few words and even fewer emotions, refuses to accept this explanation. He is sure that something is off.

Like the first flurry of snowflakes that foreshadows an avalanche, these doubts quickly transform into icy descent to an underworld of crime in his relentless pursuit for justice—a mission that more than a mere act to balance the scale, is also an expression of a father’s overwhelming need to protect his child, even in death. Skarsgård, with his stoic performance, is the perfect vessel for this quest as he begins to exhibit the type of efficiency and ruthlessness that you would expect from a hardened criminal. But the more he digs, the more he realizes that what was made to seem like a simple death is only actually the tip of a much deeper, darker iceberg.

Thus, what initially seems like the setup for a typical revenge film slowly unravels itself in unexpected ways, especially through its handling of tone. Embedded with the same cosmic irony of the films by Joel and Ethan Coen, as Nils embarks on his mission to track down those responsible for his son’s death, he inadvertently sets off a chain of violent events that escalate far beyond his control. Moland employs an almost absurd comedy—black as night—highlighting the futility and randomness of violence.

A deadpan sense of humor, whether it’s Nils’s casual interactions with law enforcement or the ridiculous missteps of the local gangsters, constantly undercuts its own gravitas with the absurdity of the situation and further punctuates the most brutal moments. The characters, such as the local crime boss known as “The Count” (a chillingly charming Pål Sverre Hagen) and his band of henchmen, are drawn with an exaggerated, almost cartoonish flair that enhances the film’s absurdist undercurrent. They aren’t just villains; they are pawns in a far larger game of fate and retribution. And every action—no matter how innocent or malicious—seems to propel the next step of the chaos.

This isn’t your typical fast-paced, high-octane world of car chases and shootouts, but a slow burn where the violence feels as inevitable as a blizzard’s arrival and just as numbing. The violence, like the frozen expanse that closes in on the characters, is framed with a peculiar sense of detachment. Blood is spilled with clinical precision, and characters drop dead with a casual indifference that only amplifies the dark humor.

This combination of dry humor and extreme brutality reflects the coldness of the environment, where human life is often as disposable as the snow that constantly covers the ground. The film never flinches from showing the devastating cyclical nature of violence, but it does so in a way that is at once horrifying yet oddly entertaining, striking a perfect balance between the macabre and the comedic that paints life as harsh and the will to survive seems to justify any means necessary.

As the body count rises and the stakes grow ever higher, Nils’s transformation from grieving father to ruthless vigilante becomes more pronounced. His personal vendetta, which snowballs into an avalanche, becoming a full-blown gang for control of the region’s drug trade, begets far-reaching consequences for everyone involved. Enter the Serbian drug dealers, led by an always scene-stealing Bruno Ganz, whose icy demeanor and chilling precision are the perfect counterpoint to the bumbling local thugs that Nils first triggers. This second act is full of misunderstandings, mistaken identities, and escalating chaos. Yet the film retains a sense of control. The tension between the rival gangs is as frigid as the mountain air, each move carefully calculated, and each mistake comes with its own fatal consequences.

The deadpan humor persists, but there is a growing sense of inevitability, as if Nils’s violent journey is as much about his own self-destruction as it is about seeking justice for his son. Yet, the film’s real strength lies not only in its intricate blend of comedy and violence but in its exploration of the father-son relationship. As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that the film is as much about Nils’s struggle with the world he inhabits as it is about his relationship with his son. His journey is not just one of revenge but one of mourning, acceptance, and the realization that he cannot undo the past.

As Nils confronts the consequences of his actions, the film circles back to its central theme: the relationship between fathers and sons. There is a haunting undercurrent of loss and legacy that permeates the film, and Moland underscores this with a quiet, almost tragic resolution. Nils may have sought revenge. However, in the end, what he is left with is not justice or redemption, but the recognition that his journey was one of futility—a reflection on the limits of paternal love and the inevitable toll that violence takes on both the avenger and the avenged.

![The Scoundrels [2019]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – A Standard Fare Which Could Have Stood Out with a Different Approach](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/The-Scoundrels-1-high-on-films-768x432.jpg)