Matías Piñeiro’s new, hour-long film, “You Burn Me,” is a dazzling, mind-bogglingly rich, intertextual hall of mirrors. Relying on Sea Foam, a chapter from Cesare Pavese’s Dialogues with Leucò and Sappho’s poetry, it skitters off into a provocative meditation on the ellipsis in translation between the page and screen, as well as summoning the viewer’s sustained engagement. For all its preoccupations with death, this is a lively film, restlessly pushing against boundaries. It can be overwhelming and demands multiple revisits for you to fully appraise the massive scope of what Piñeiro is proposing.

The film recently had its US theatrical run via Cinema Guild. HighOnFilms’ Debanjan Dhar sat down with Piñeiro to discuss the art of detours, his abiding interest in variations, weaving incomplete narratives, resisting totemic representations, and more.

Debanjan: This film is full of offshoots, diversions, and detours, there’s this constant branching out at play across a huge temporal expanse. You’ve spoken about not quite knowing how to shoot the Pavese text and that was the primary attraction. Can you trace back to what was the first conceptual detour you felt drawn, from the text occupying the center?

Matías Piñeiro: When I first tried to read the text, I didn’t finish it. I left it aside. I went back to it months later. I found this particular chapter and was attracted to it. I had difficulty with the text but suddenly not with this chapter. Unlike the Shakespeare films, this text demanded a different treatment. It required to be shot differently. I didn’t know how to take these words and put them in a film. I needed time, a form of production that would allow me to fully explore and experiment. I needed to fail a lot and the scope to be ineffective.

Only then from all the failures, I could take the elements that worked. I shot six hours of footage. You learn only by making. I cannot make hypotheses. I needed to try out all possibilities and work from the findings. This couldn’t have been born sitting at a computer or a fancy residency. I had to go to Torino, shoot with my friends in San Sebastian, shoot the papers in New York, and then Buenos Aires. Many of those were fake paths, but some did work.

I’m a stubborn filmmaker. I had to see what the text was asking. The difference from the other movies allowed me to see that style or the way you like to work isn’t a pre-set of an Instagram filter you can just plaster on anything. The text you choose to work with transforms you. The film isn’t pure fiction, it’s a hybrid. This particular text of Pavese is philosophical and essayistic.

Debanjan: When did you first come across this text?

Matías Piñeiro: During the pandemic. I did know of it previously, through the films of Straub-Huillet. Probably I bought it before the pandemic in Buenos Aires and took it to New York, where I live. I reread it during the pandemic and felt a connection.

Debanjan: Talk to me about your relationship with Pavese’s work, confronting the density of the text and finding a foothold. While relaying a sense of Pavese, how vital was it for you to reject the male myth of the tortured artist, to show him containing contradictions?

Matías Piñeiro: When you read Pavese’s work and also come across the figure of Sappho who killed herself, it’s a natural impulse to have a morbid fascination. But there’s more. Pavese also wrote the dialogues of Britomartis, who’s so lively. In him, we can see two sides. This tension attracted me. I do admire Pavese as a thinker but it was important to question him. Sappho’s poetry became central to this interrogation. I hope this film doesn’t push further the romantic myth of the artist killing himself but that it goes in another direction. I try not to make him a totem. Adapting the footnotes allowed us to bring in another force, not just restricted to Pavese, but also Sappho, the bacteria thing. These expand the text and not totalise Pavese’s influence.

Debanjan: With fragmentation, there’s always a danger of making it seem too forced and fake. Was that ever a consideration while you were working on this film?

Matías Piñeiro: I was aware of the many possible systemic programs that I could enter. I always knew I wanted to film with a Bolex camera and that there would be no direct sound. I thought this could be like a Marguerite Duras film. I knew I wanted some shots more than twenty-five seconds because I wanted a pattern of editing.

They are mostly short takes. Paula Tomás Marques, the co-cinematographer, taught me to think about staging for the sake of editing, not just with Bolex. You need to cut more, not in an experimental way. Treat it as a narrative filmmaker. The film also had the idea of shooting a lot of imagery. So it was a combination of what the technology, the Bolex gives you, the non-sync and going against it, having longer shots sometimes with sync, putting voiceover, fooling around. I knew these could all become a pattern and was conscious of breaking it.

Debanjan: Talk to me about the writing process. I know you don’t have that script fetish; for your earlier films, you have said you finished the script close to the shooting schedule, preferring to talk through it with collaborators and actors as a way of passage. I assume this shifted significantly while making this film?

Matías Piñeiro: I was constantly shooting. The core was Pavese’s text. I needed a moment where I could address Pavese’s biography, and then go to the hotel where he killed himself. I also thought of putting some bits from another of Pavese’s texts, Among Women Only, which Antonioni adapted into Le Amiche. But I ultimately threw it away. I used the tool of the scroll for both scripting and editing.

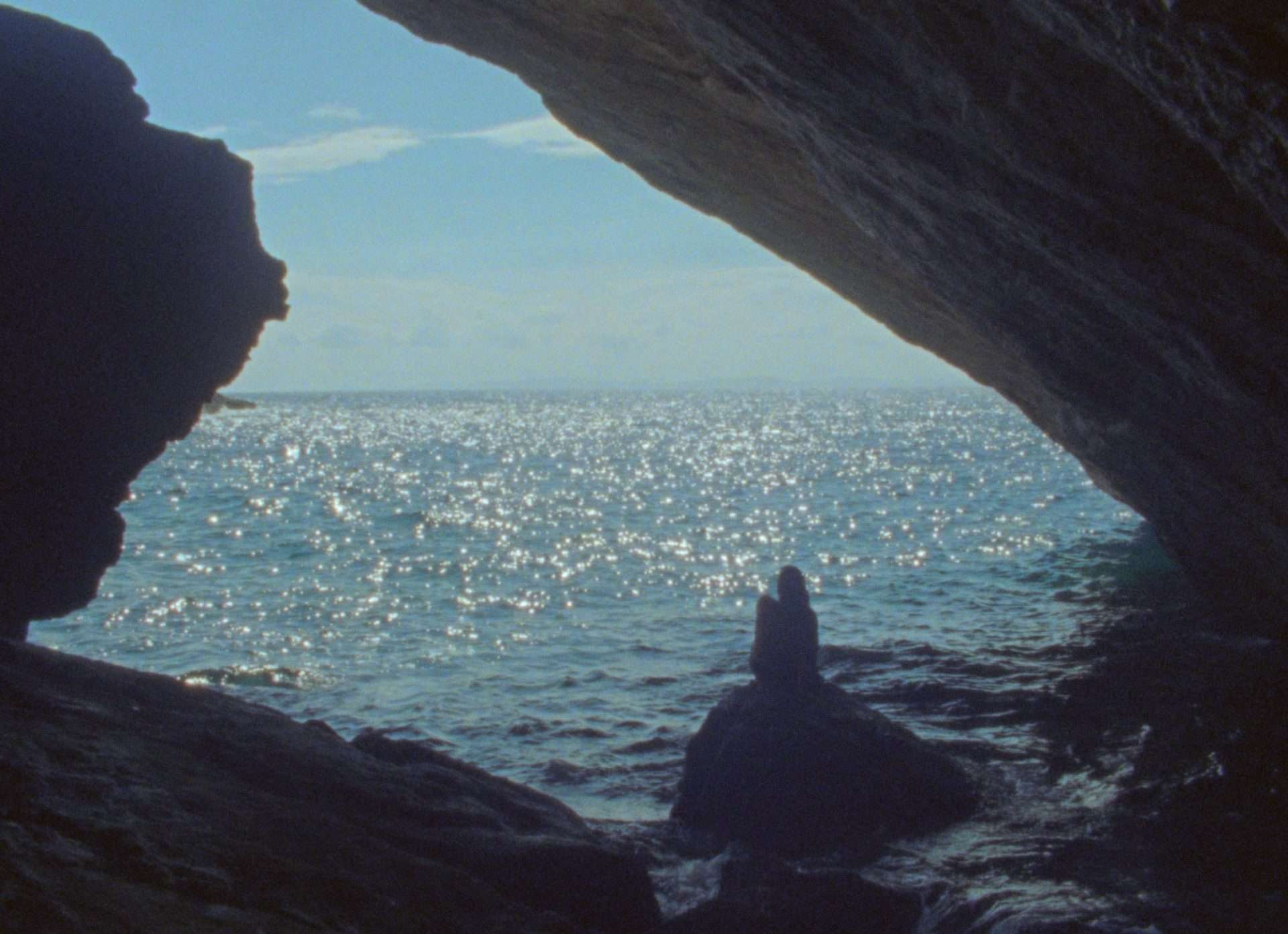

I wrote the whole text, leaving a distance between the lines of Sappho and Britomartis. In between, I put the shots. I put the detours on the upper part of the scroll. With that object, I could edit the film. There was never a script per se. I just worked with Pavese’s text and the imaginary spaces that came out from it: Torino, the cliffs, going to Athens, the museums, and the sculptures. Pavese’s text made these sequences come out. I’d then explore these threads in the edit. I kept myself in a constant state of shooting and editing. The writing was done through shooting.

Debanjan: You call your earlier films alternate narratives and You Burn Me marks a radical departure. Yet, there’s a hint of a narrative, like the girl being a lovesick biology student. Why did you choose to keep that?

Matías Piñeiro: One additional layer became Sappho’s poems. I wanted people to memorize her poems. Sappho could also be trafficked via dialogue. I played with the idea of adapting: her poems, the footnotes, and Pavese’s text. But of course, you can’t really put across a poem into one visual meaning. I needed to keep this adaptation very loose, and broken. So, these moments of narrative that appear, I was sure they should never become a full circle, much like Sappho’s poems are just fragments. I sought to weave impressions and incomplete narratives.

Debanjan: About your Shakespeare cycle of films, you like to call them not Shakespeare adaptations but variations, (because you are using fragments). Would you say the same for You Burn Me?

Matías Piñeiro: In a way, yes. I do like the idea of variations that allow me to bring ambiguity to the core of the image. Perhaps it’s my love for André Bazin that pushes me to this, how to capture the ambiguity of life in images and how to make them three-dimensional. In variation, I find musicality, a constant movement that resists fixities of just one way or totemic impulses. I know, in cinema, we have to be firm, but we also have the possibility to bring out questioning and doubt. Variation, to me, becomes the device for exploring this.

Debanjan: I was recently speaking to your friend Lois Patiño for his film Ariel, and he was talking about both of you working together on Sycorax, how your inclinations have rubbed off on each other. He was saying he’s now getting more interested in acting and representation, and your new work reflects greater sensitivity to landscapes and contemplations. Tell me about working with him…

Matías Piñeiro: It was beautiful to work with him. We were coming from such different heights. The point of crossing was Sycorax. I felt I needed to work out a different idea of rhythm, nature, silence, shooting landscapes, something not just about words and acting. It was like being hit by his energy, not about making a film like Lois would. The experience allowed me to think out of Buenos Aires explore other methods of production and be more adventurous.

Sometimes Lois shoots alone with his camera. Many moments during making You Burn Me, I imbibed that. I came from a traditional film school, where you learn about various roles of assistant, production design, camera, and sound. Lois’ way of making cinema is more experimental in arranging and approaching time and schedule. Working together on Sycorax, we made an interesting bond. Some days, I’d be the assistant and he on the camera, on other days vice versa. He’s a very intelligent, warm person to work with.

Debanjan: I want to take a couple of recommendations. Any new films/emerging filmmakers that caught your attention of late?

Matías Piñeiro: Paula Tomás Marques just premiered her film, Two Times João Liberada, at this year’s Berlinale. I’ve also been watching a lot of Mikio Naruse’s films, because there was a recent retrospective in Buenos Aires. I’ve been surprised by how strange he is. He looks very classical but if you pay attention, he’s making very rigorous decisions with structure and storytelling. They are not classical at all. In terms of what he chooses to show and keep out of view, it’s quite peculiar. Well, I really admire the films of Hong Sang-soo. I think he’s always thinking of the encounter between production and mise-en-scène, ambiguity and fiction.

Debanjan: Finally, you said you’ve been working on a Petrarch text, there’s also a Henry James adaptation in the pipeline. Do you see your approaches and techniques on this film rubbing off, carrying over into those projects?

Matías Piñeiro: I’ve already started shooting the Petrarch film, where I’m taking a few texts of his. I’m mixing two, Remedies for Fortune Foul and Fair, and a letter he wrote to his friend about a mountain ascent. It has similarities to You Burn Me but I wanted a little bit more of narrative. I think I’ll make it work all around a mountain. I’m shooting on film. It’s quite comedic and has much to do with Shakespeare, because, of course, he was taking from Petrarch. For the Henry James film, I’m writing the script. I need to polish it. I’m transcribing every page of the script. I hope to shoot the Petrarch film this year and next and start the Henry James after that. So, yes, I’m moving into a bit of fiction but I’m sure I’ll find some detours and weird stuff (smiles).