Scrapper (2023) opens with the proverb, “It takes a village to raise a child,” and then that proverb is cut over with a yellow crayon, and the screen is then filled with a scrawled sentence of that same yellow tinge: “I can take care of myself, thanks.” As a viewer, you can’t help but guffaw in wry disbelief, and yet watch as new actress Lola Campbell, playing 12-year-old Georgie, effectively looks after herself, having created an elaborate ruse with the social services that she is living with her uncle “Winston Churchill.” She manages to earn money with her best friend Ali (Alin Uzun) by nicking bicycles and selling them to the local cyclist cum mechanic for parts.

There is a street-smart and sweet camaraderie between Ali and Georgie. This helps them stand apart from the rest of the kids in the projects where the story takes place. Moreover, director Charlotte Regan takes her time fleshing out this friendship between Ali and Georgie while slowly easing in the new intruder in Georgie’s life.

The new intruder, who entered by climbing over the fence of the house, is Georgie’s estranged father, Jason (Harris Dickinson). His platinum blonde hair, bowler jacket, and generally looser attitude aren’t ones to impress Georgie. But Ali tries to make her understand and even argues with Georgie. As a result, she has a hard time trusting people.

It turns out so does Jason, who doesn’t appreciate the kids rifling through his phone. But as Ali goes off caravanning with his parents, leaving father and daughter alone, “Scrapper,” true to its name, becomes a scrappy story of two underdogs in life. They reckon their existence with each other and realize that reality will force both of them to grow up and accept each other.

At this point, there is a certain cynicism to watching a Sundance independent feature—the cinematography, the editing, and even the characters in the screenplay. Movies like “The Florida Project” and even “Aftersun” will automatically come to mind while watching “Scrapper.” Perhaps the comparison seems inevitable but also decidedly unnecessary.

It is a weird statement to construe that even independent movies are becoming predictable, but is predictability truly bad when the genuineness of storytelling shines through? The moments between Jason and Georgie as they slowly start getting closer are heartwarming to watch, ideally helped by the chemistry between Dickinson and Campbell.

Dickinson is fantastic as the rough-around-the-edges father. However, it is Campbell who truly impresses with her debut. The street-smart, tough exterior hides the child underneath, who dreams of making a tower with all of the cycle parts nicked, such that one day she could reach the sky to her mother. In fact, Lola Campbell has that rare ability to look effortlessly vulnerable.

The scene between her and Dickinson when they are walking on opposite sides of the street, and Dickinson is trying to make her smile by pretending his shoe to be a phone or playing with a dog on the street, and a smile flitting through Campbell’s face, is beautifully done. That slowly developing bond is heartening enough to pull through some sequences, which feel more like improvised skits or little asides.

Director Charlotte Regan also tries to bring in different filmmaking techniques and sort of a documentary approach to some of the sequences, especially while interacting with the ancillary characters. It is debatable whether the different filmmaking sequences were needed. But they definitely ensure that the exposition is delivered in a unique manner.

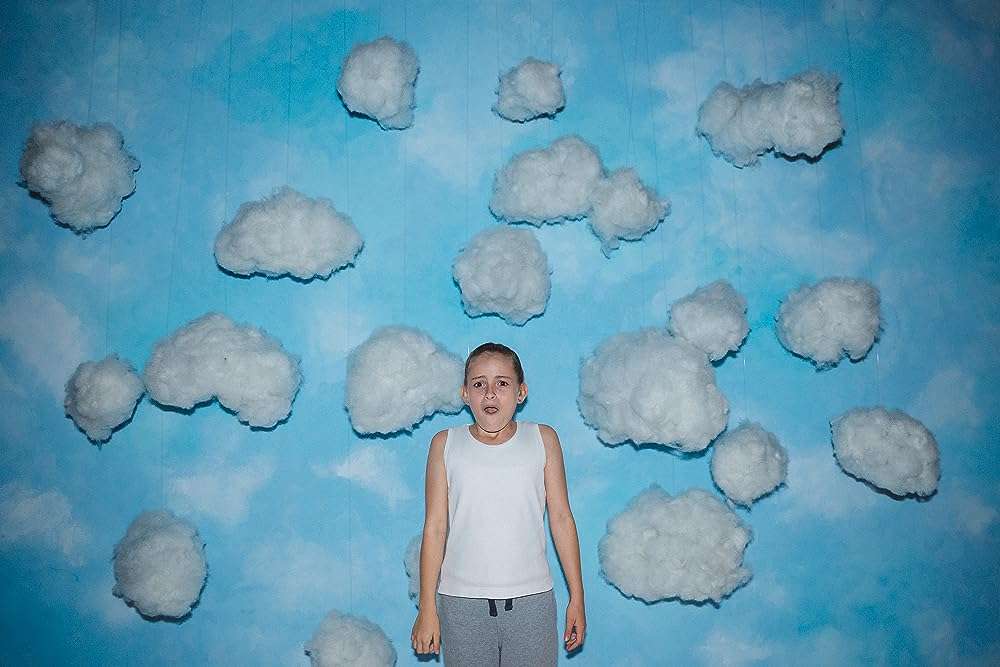

The most impressive bit is how Regan chooses to show the child’s perspective, whether it be Ali’s fascination with spiders and the spiders’ resultant interactions with each other through comic book bubbles or how Ali and Georgie imagine what Jason’s profession could be, and Dickinson appears in front of them through the garb of a vampire, a gangster, or a businessman.

All of these filmmaking wrinkles give “Scrapper” a unique and colorful vibe that could be lazily termed as predictable. However, predictability doesn’t account for the poignant gut punch one gets when the child finally utters to the father, “Once I know you, I can’t know you.” Regan manages to maintain the balance between playfulness and emotional authenticity, which elevates “Scrapper” with its giant beating heart and underlying simplicity.

![Little Women [Season 1] Episodes 7 & 8: Recap and Ending, Explained – How do Choi and In-Joo catch the Fake In-Joo red-handed?](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Little-Women-Season-1-Episodes-7-8-768x449.jpg)

![The Nightingale [2019] Review: As Misguided As It Is Polarizing](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/the-nightingale-jennifer-kent-768x403.jpg)