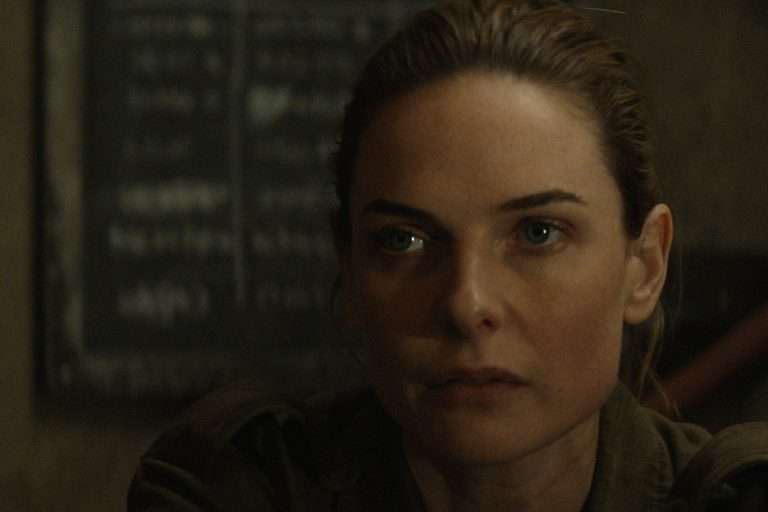

“The Black Garden” is a film filled with tragedy. It circles lives hopelessly ravaged yet persists in staking its claims on what they cherish and refuse to let go of: community and homeland. Both are foundational to a sense of identity. The threat of uprooting is an attack on selfhood that is built through kinship with the land we occupy, building our homes and lives, and forging affective networks of friendship. Director Alexis Pazoumian trains his gaze on the merciless vagaries that are visited upon the inhabitants of Talish, a village in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, located on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

After the Soviet collapse in the 1990s, the largely Armenian-majority populace of Karabakh declared themselves as a republic, resisting integration with Azerbaijan and asserted its independence. However, it wasn’t recognized as a republic by the international community, triggering a spate of bloody fighting that has taken on various manifestations through the decades and continues to this day. A vicious Azeri military offensive left Talish in devastation. In December 2019, only twenty families returned to the village, hoping to reassemble and piece back together their shattered homes despite a stark knowledge of the utter futility of rebuilding a life on such uncertain, deeply hazardous ground.

Pazoumian doesn’t plunge us into the heat of aggressive incursions mounted by the Azeri army and the violent clashes that precipitate the constant state of unpredictability and imminent exodus. Instead, we are made to linger with the shadow of the chaos and bloodshed cast on the place and its people, forcing their lives into permanent instability. The conflict has a solid, unwavering presence almost everywhere in Talish, in the mass of debris lining every nook and cranny and the militarisation making its way even into classrooms. Kids are taught how to handle and aim Kalashnikovs. Patriotic songs are a fixture in rare moments of merrymaking.

Droves of youths sign up for recruitment into the military forces. Spanning three years and interweaving perspectives pitched by three generations of men, the film traces a trajectory of despair and accentuating bleakness, from losing everything to taking on arms to defend one’s homeland, holding no fear in the numb absence of one’s loved ones. Besides a twentysomething Erik and the middle-aged Karen, we follow two teenagers and close friends, Avo and Samvel, navigating their frightening circumstances when, at any moment, they might be ripped apart.

Residents could choose safety by evacuating their homes and seeking refuge in the Armenian capital of Yerevan, but the tug that binds them to their native village is an overwhelming force of its own. Though as the final section warningly suggests, even the capital might not be immune to the Azeri invasion. The sobering documentary dangles its brutal questions with directness – how can you casually fling aside ties to your home? It’s gut-wrenching to witness people being systemically stripped of the most fundamental humanitarian safety and protection, failed in every possible regard as they struggle to patch together a life in all its corrosive, horrifically amped-up volatility.

The barbaric shelling happens with such extreme suddenness the act of leaving barely gets the time it needs. Villagers are sharply aware of the immediate, immense danger their lives would be shrouded in if they choose to stay back, yet they make that call. Many keep returning to the precarious, bordering region of Karabakh, in which Talish is situated, despite the jeopardy and desert at the onset of strikes. Karen recounts having had to flee thrice due to the war.

However, the intertitles dutifully popping up and dispensing a sort of chronological function work to the film’s detriment. Sure, it gives a larger sense of the conflict’s timeline and rampant, escalating intensity but often it jerks us out of a particular moment in the narrative, interrupting an emotional thread of connection. Where is the shelter these people ought to have? The entire world seems to have turned itself away.

“The Black Garden” is a piercing, rallying appeal against this abandonment, calling on us to care and engage deeply not just for this particular conflict but for any such semblance of it that has echoes almost everywhere in the fractured contemporary moment. Powerfully reinstating an unbreakable bond with one’s home and land in the face of absolute muscular opposition and intimidation, Pazoumian’s film is an essential and galvanizing work.

![Sertania [2020] ´CIFF´ Review – A Symbolic and Experimental Western](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Sertania-1-higonfilms-768x269.jpg)

![Poser [2021]: ‘Tribeca’ Review – A volatile dissection of the need to belong](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Poser-2-Tribeca-highonfilms-768x432.png)