“I really wanted to make a new kind of newsroom thriller which reflected the anxiety that I felt while watching the news.” – Director, Vinay Shukla.

Since premiering at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival and winning the Amplify Voices Award, director Vinay Shukla’s latest film, While We Watched, has taken the film festival circuit by storm. The film had its Australian premiere at the 2023 Sydney Film Festival and its South Asian premiere at the 2023 JIO MAMI Film Festival earlier this month, and then at the 12th Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF). The accolades for the film don’t stop here. This weekend, the film bagged the Short List Directing Award and the Short List Producing Award at 2023 DOC NYC, the largest documentary film festival in the USA, the first time a film has bagged the double (directing and producing awards) at the festival.

Film critic, programmer, and High on Film’s Virat Nehru spoke with director Vinay Shukla about his film and what prompted Shukla to pick Indian journalist, news anchor, and 2019 Ramon Magsaysay Award winner Ravish Kumar as the subject for ‘While We Watched.’

In the conversation, Vinay Shukla explains his motivation to make a new kind of newsroom thriller, why many people of his generation have stopped watching the news, the challenge of making nonfiction films in a country where the majority prefer to watch fiction features, and despite his idealism taking a beating, his steadfast belief that the younger generation has the ability to navigate the current disinformation crisis and make art that reflects their experiences.

Edited excerpts from the conversation below.

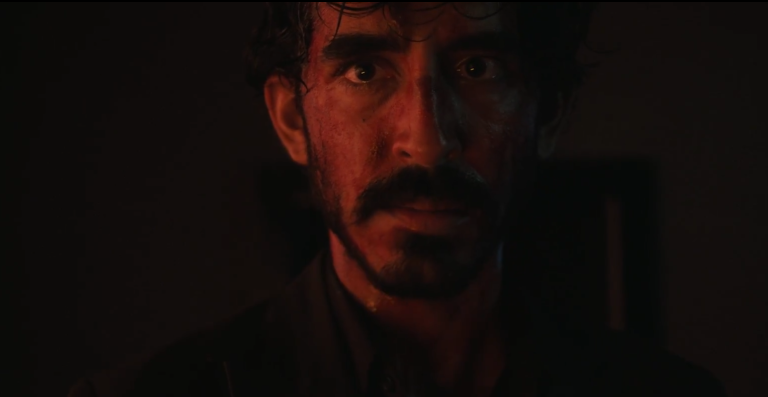

Vinay: My film is about Ravish Kumar. He’s a very famous, very hotly debated news anchor in India. He used to host a 9 PM show on NDTV every night. I came across some of Ravish’s broadcasts. And unlike a lot of other news channels and news anchors who were saying that my audience is number one, here was Ravish looking at his audience and saying – the problem is that you’re still watching the news. You need to stop watching the news. YOU are the problem. So, I found that to be quite strange and funny. To see somebody on the news telling people to stop watching the news.

I felt that here was a person who was very vulnerable. He was a protagonist who had seen a better time, and he was wondering if he was relevant anymore to his audiences. And he was challenging his audiences, he was pushing them back. I found that to be a good starting point. I was aware that something in the news cycle didn’t seem right, and I had stopped watching the news.

My friends in India, my friends across the world, a lot of us have just stopped watching the news. Considering that news is a major system of public information – people come to the news because they believe that they will learn something that will make their lives better – it was very strange that so many of us have cut ourselves off from the news. So, I really wanted to make a new kind of newsroom thriller that reflected the anxiety that I felt while watching the news.

The experience of consuming news, I believe for me, is not a pleasant one in today’s times. Whenever I watch the news, it makes me really, really, really anxious. So, I wanted to make a high-octane film, which was fuelled by the anxiety that I feel every day. And that was an idea that I had when I was starting out. That it’d be interesting to make a film like this.

Virat: You mentioned that you thought of Ravish as vulnerable, which is interesting because the persona that he has when he’s doing his broadcasts is of this irreverent, ‘last man standing’ kind of journalist in an era that has become dominated by news anchors where news has become entertainment. Ravish seems to be telling his audience to wake up to this reality. Were you able to sense that there was something more interesting in him as a subject before you started the doco? Or was it something you realized as and when the doco was being formed?

Vinay Shukla: Of course, I had some idea prior to starting because it’s reflective in his [Ravish’s] work. His sensitivities, his concerns, his faults, and his biases they’re all reflective in his work. So, I had some idea that there is a richer inner life here. The contours of that life, the shades of it, you discover that while you’re shooting. Let me also add something here. I have shown the film to journalists across the spectrum. And people who don’t agree with Ravish also say that the film is about them. We’re all going through very, very universal experiences, Virat.

We assume that those who are not like us don’t feel the same things. The film is a very personal story about adult loneliness; about a person in his fifties trying to soldier on in a career that seems very keen on pushing him out. It’s a story of a bunch of people trying to figure out if the world out there really cares about the work that they’re doing.

I have been told continuously that it’s the same experience across the spectrum. I’ve shown the film to entrepreneurs, who have said the film has resonated with them because this is exactly what happens in entrepreneurship. It’s reflective of the struggle of adulthood. And I take some respite in that. Because then, I believe there is a way to have a conversation about how to build a better future, even with those who we disagree with. And that’s my ambition with this film. That, in what it explores and in what it reveals to you about Ravish and so many other journalists, we can find some common thread about how we are all similar and how – I hope – that we are all trying to build a better future, and we’d have to build it together.

Virat: One of the key motifs the film keeps coming back to is that there seems to be a schism beyond repair in the society we’re living in, where people are getting fed information through different sources, and they get to choose the sources that they want information from. And there is a pre-existing bias in people based on where the information source is coming from even before they receive the information.

So, I already think that if a certain Ravish Kumar is saying something, he has a certain perspective, or a bias, or a leaning, and I’ve already, in my mind, pre-associated the information that’s coming from his mouth. The problem that we face today in a very polarised society, where people can pick and choose their sources of information, is how to reach out beyond our echo chambers? By positioning the film as a universal experience of loneliness in adulthood, do you think the film is trying to solve that problem?

Vinay Shukla: This idea that we are able to choose our information sources it’s actually being challenged. Because the information right now is coming to you pre-packaged from various sources. It can be a news channel, it can be tech companies via social media, it can be WhatsApp. Your news is coming in pre-destined packages. And it’s coming in an extremely invasive way. It’s violating any agency that people have. The fault and the course correction there lies on various levels. For example, it’s also about our own systems existing at an individual level. How do we discern information? How do we consume information? What’s a positive bias? How do we understand bias? What’s a negative bias? This idea of completely unbiased news is very amateurish.

News deals with the same challenges that society itself deals with. And, of course, the news will come with biases because people are trying to figure out how to do their job better. Anyway, that’s a larger dialogue. I’m saying that there are personal systems of how we read information. There’s a larger problem of how institutions themselves, news institutions especially, are just not equipped intellectually and financially for the problems that we are facing in the world right now. I keep talking about this again and again and again. We are living in a world of complex problems. Migration is a complex problem. Climate change is a complex problem. Determining left-wing bias and right-wing bias is a complex problem. Capitalism is a complex problem. The pandemic is a complex problem.

In a society like India, wherein there is such a huge information inequality amongst people – you can be working for the same organization but have completely different lives. When you go back home, you don’t have access to the same information resources. Our journalists within news organizations just aren’t trained for complexity. It’s mind-boggling. We went through two years of COVID-19. You should go and find out the number of organizations that did COVID-19 training amongst journalists – to help them understand what it is, what they can do to understand it better, and how they should be reporting on it.

And I can tell you that the absolute lack of that did cost us in terms of how much misinformation was there during COVID-19. The film is a very emotional film. The film speaks the emotional language that I speak. I like being able to communicate with even those whom I disagree with. I make documentary films in a country where people run away from documentaries. If I go and tell my parents I want to show you a documentary, unless and until it’s mine, they won’t watch it.

Virat: Even the way people use the term ‘documentary,’ it comes across as a pejorative in India. For example, if a fiction feature is boring, they would say, film documentary jaisi lag rahi thi.

Vinay Shukla: You’re absolutely right, Virat. So then, if I’m making documentaries in this country, it’s very important for me personally that I make it in a manner that is accessible to audiences. I came to filmmaking because I thought films and narratives can make the world a better place. That’s why I came into this field. My idealism has taken a beating, but I still believe it. So, I have to make films in a language that people understand. And the film’s emotional grammar comes from the emotional grammar that I have. I am really trying to communicate with people on a very fundamental level. To try and engage them with an emotional narrative and with an emotional truth that I have. But the dialogue from there onwards cannot be built on emotions.

That has to be built with intellectual rigor. So, if we are honest about building better journalism, then it has nothing to do with which political party is in power and which news network is right or wrong. We have to build better institutions. We have to build better systems, and we have to build greater intellectual rigor to be able to build a more sustainable path to the future. Otherwise, everything is a flash in the pan. Some governments will lose elections. Somebody will win elections. Somebody will win an award. Some news organizations will shut down. Some new ones will start. And we will just be going through the same motions and making the same mistakes that we have in the past.

Virat: You said that this is a very emotional film. The thing that really struck me, quite personally and quite deeply, was the impact of what Ravish is doing day in and day out on the people around him.

Vinay Shukla: People who are in public life – they may be in the film business, they may be in the journalism business, they may be in politics, they may be high-ranking public officials, their families very often have to pay the price of their jobs. And especially people who are these hero figures of sorts. Very often, the cost of those heroic ambitions has to be paid by their families. And the Ravish family has definitely paid that price and continues to do so to date. I wanted to make an inclusive portrait. I’m very close to my family.

And my family is very loving and supportive of me. So, that’s another reason why I focus on the role that our families must play. It goes back to my earlier point that we’re all actually very similar. It’s not like the people we disagree with don’t have the same support systems or aren’t looking for the same support systems. Of course, they are. And that’s what unifies us.

Coming back to the disinformation crisis, there is, without a doubt, an incredible disinformation crisis that we are faced with right now. I wouldn’t have made this film if I didn’t feel concerned enough about that crisis. But, with regards to the young people out there, the good thing about young people – because I used to be young once – is that they’re able to find the right things. Irrespective of what people may think, that the young are not getting access to the right information, the young will be fine.

They will build a better narrative. I made this film also because there is a fifteen-year-old version of me in some school somewhere who doesn’t agree with what they see on TV. I’m making this film to hopefully tell that person that, hey, you’re not alone. I am here, too. It’s an act of solidarity and kinship from my end. What we essentially need to do is give them [young people] better tools, give them better conversation points, give them a better system, so that they can find themselves better representation. The young will be fine, but our job is to give them better tools.

Virat: The other point that you raised and touched upon was about the form itself. You mentioned that making documentaries in a country that shies away from the form and considers them to not be viable is challenging. Does something like ‘The Elephant Whisperers’ winning Best Documentary Short at the Oscars change anything? Does that translate to any kind of change in the perception of documentaries as a medium? What is that challenge like – knowing that you are dealing with a form like you said, which is not very well received by a lot of people, but you want to present it in a way that is engaging?

Vinay Shukla: With regards to whether ‘The Elephant Whisperers’ winning will have an impact, it most certainly will. Even something like ‘All That Breathes’. There are some incredible filmmakers working in nonfiction right now. There is Shirley Abraham and Amit Madheshiya who made a film called ‘The Cinema Travellers’ a few years ago. Rahul Jain has made ‘Machines,’ and he’s also made ‘Invisible Demons.’ My co-director on the last film [An Insignificant Man], Khushboo Ranka, is doing some incredible work in fiction and nonfiction. She’s also my producer on this film. Anand Patwardhan has a new film, ‘Vaisudhaiva Kutumbakam’ [The World is Family].

There is incredible energy and buzz about Indian nonfiction right now. And I get emails from young people all the time who are looking to understand how they can do this. The thing about young people, and anyone who has been denied representation, is that if you don’t give them representation in popular culture, they will go and build it themselves. There is no way for people to contain it; you cannot! When I was in my early twenties, and I was starting out trying to make films, I took to nonfiction because I realized that ye camera to mere haath mein hai and there is nothing that can stop me.

The video function within DSLRs had just been introduced, with the depth-of-field option. So, people were losing their minds. I took to it immediately, and I started shooting with my family. I would talk to my mom, talk to my father, talk to my grandparents, talk to my siblings, talk to my friends, and I would shoot those conversations while I was talking or while they were talking to each other. Because I was trying to learn how to shoot.

I was trying to learn life ko films ke jaise kaise dikhaayen through this process. That way, I started to learn how to shoot between people without making people conscious. I am pretty sure that the young people today are going to do the same thing. Kartiki [Gonsalves] winning that award for ‘The Elephant Whisperers’ is a major boost because there is the feeling that there is glory and validation, there is money, and there is fame at the end of it all. This is essential.

Recognition is very important for artists. Kartiki, Guneet, and their entire team have managed to achieve something that felt absolutely impossible. So, more power to them. With regards to the language of my own film, when I’m making these films, I try and think of what are films that I enjoy. For example, I love Nuri Bilge Ceylan. I can go on and on listing names. There are people whose work I have seen and been completely inspired by. When I come to making my films, I am trying to think – can this film look like my favorite filmmaker’s film?

Because you’re trying to find yourself, right? Your initial drafts are that, and then you realize this is not working. I need to find my own voice. You start and build from there onwards. My challenge really was – when you watch newsroom thrillers, very often, it’s about a bunch of people getting together, doing a story, and changing the world. My film is not that. Agar main wo kahungaa to wo jhooth hoga. And I would have made some kind of an emotional and soppy film. This wasn’t the feeling I wanted the audience to leave with. Currently, the way the film stands right now, it’s a 90-minute trauma capsule. With some redemption at the end.

Virat: How has the reception of the film been at DOCNYC? The film has won the directing and producing award double, a feat that no film has accomplished before. Does this reaffirm your view that the film has a universality, which is why it’s connecting with people across cultures and boundaries?

Vinay Shukla: New York has practically been home to this film. We premiered there last year at DOCNYC ’22. Then, we had a theatrical release at the IFC Center in July ’23, where John Oliver and Amy Goodman did Q&A’s for us, and the film ran in theatres for a month. Being then invited to DOCNYC ’23 as part of the Short List was a significant honor. Some of my favorite films from this year were playing in the same category, and it was beautiful because I went to their screenings, and those filmmakers came to mine. We have all been traveling alongside each other over the last year, but DOCNYC is where we finally saw each other’s films. So, I just loved that experience – to be able to share the film with audiences and fellow filmmakers at DOCNYC.

With regards to the film winning, I’m very grateful. Honestly, the journey of this film has been humbling. When we were making the film, most people thought that it wouldn’t see the light of the day. People would murmur in my ears: “Be careful. This is a great film, but it’ll never get out. You might as well start making another film.”

I’m lucky that I have an incredible team behind the scenes, which continues to work every day and open doors for the film. And I’m grateful to DOCNYC, the jury, and the audience for the award. We’ll see over the years ahead what kind of life this film enjoys in the minds and hearts of people. So far, so good.

![Deadstream [2022]: ‘SXSW’ Review – Evil Dead for the Twitch and Youtube Livestreaming generation](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Deadstream-768x432.jpeg)