The Academy Awards exist as a barometer to determine what is popular within a given year, and do not always serve as a broad celebration of its crowning achievements. Although the Oscars have done considerable work in recent years to recognize international cinema and films from different genres, there are still several instances in which the current set of Academy Awards voters feels out of touch. Unique films that took narrative risks like “The Testament of Ann Lee” and “If I Had Legs I’d Kick You” didn’t make the Best Picture lineup, and more boundary-pushing, confrontational cinema, such as “Warfare” and “Eddington,” was never in serious consideration.

Although there have been great and terrible lineups for Best Picture nominees, the ten films selected to represent 2026 at the Academy Awards could be seen as “acceptable,” more or less. There are at least four films nominated that are almost guaranteed to be remembered as masterpieces in years to come, as well as a few head-scratching nominations that are bound to be received more derisively after the heightened emotions of award season pass.

It’s remarkably a year where the nominees came from a diverse selection of studios, a fact that now feels somewhat grim given how frequently Hollywood seems to be merging its entertainment companies. The Oscars have the chance to reward a generational masterpiece in 2026, and it remains to be seen if they will do it. Here are all of the 2026 Best Picture Oscar nominees, ranked from worst to best.

10. “Hamnet”

2025’s most overrated film has become a popular choice among younger cinephiles who are prone to being manipulated, as Chloe Zhao’s adaptation of the popular novel seems oriented to create tearjerking moments without earning them. Zhao, a filmmaker best known for casting non-actors and creating realistic depictions of authentic cultures, is out of her depth when trying to impose modern sensibilities upon a period aesthetic that can’t help but feel like student theater.

It’s not surprising that actors loved “Hamnet” because it undoubtedly has the “most” acting, even if the performances lack interiority. Zhao’s film may have been about how tragedy can inspire the greatest works of art, but it’s far more interested in extended moments of passive suffering than in showing the gradual process of healing.

“Hamnet” may have sufficed as a study on how restricted emotions harm a couple’s ability to communicate with each other, but the connection to William Shakespeare and his most famous tragedy leads to an award-winning series of line-for-line readings of “Hamlet” that aren’t any more in-depth than the Easter Eggs of a Marvel film.

Not only is the film’s reading of “Hamlet” quite obvious, but it renders the character of Agnes (Jessie Buckley) into a passive observer who doesn’t have much agency in the way that her son is remembered. By the time that Max Richter’s “On The Nature of Daylight” is played, it’s hard not to think of the countless other films that utilized the track better; the best parts of “Hamnet” are those stolen from other artists.

9. “Frankenstein”

“Frankenstein” is a film that Guillermo del Toro was born to make, and it’s only made less interesting because he’s practically made it already. The DNA of Mary Shelley’s legendary novel can be found in del Toro films like “Pinocchio,” “The Shape of Water,” and “Hellboy,” so to see him return to the original text feels almost regressive. However, del Toro is incapable of making a poorly-crafted film, and “Frankenstein” is just as operatic and luscious a period gothic epic as one would expect from the Oscar-winning Mexican filmmaker. Outside of a few dodgy shots of CGI, “Frankenstein” is so beautifully rendered that it feels like a crime that most audiences caught up with it on Netflix.

Del Toro isn’t digging into new territory with the assertion that Victor (Oscar Isaac) is the real monster of the story, but he does insert some interesting commentary about the cyclical relationship between fathers and sons. Just as Victor’s father (Charles Dance) refused to approve or respect him, he ended up trying to turn his own monster (Jacob Elordi) into a respectable offspring, thus inspiring the same rage and frustration.

There are great actors like Mia Goth and Christoph Waltz who are underserved by the material, as they essentially act as set dressing, but Elordi’s performance is so beautifully understated and emotionally mature that it’s hard not be moved by the thoughtful ways in which del Toro subverts some of the tropes within the original novel. It’s not del Toro’s best, but it’s a worthy nominee.

8. “Sinners”

“Sinners” is an interesting case study in cinematic discourse because it provided smart, well-executed genre thrills at a time when the industry really needed a boost of originality. When combined with the narrative, Ryan Coogler and his film were underdogs that had to prove themselves against a studio system and media campaign determined to see them fail. The fact that “Sinners” was an undeniable cultural phenomenon led its qualities to be a bit overstated.

“Sinners” is a great work of entertainment that has more fun, inventive ways of repurposing vampire archetypes than most of the decade’s horror films, and features a score by Ludwig Göransson that will certainly go down as a classic. While it’s interested in the parallels between vampiric annihilation and the cultural rot brought upon by assimilation, “Sinners” is often awkwardly sandwiched in between its competing ambitions. Pacing is an issue throughout, and the use of both analogous evils and historical villains does lead to some confusing mixed metaphors.

That being said, the faults within the logic of “Sinners” (couldn’t they just wait until morning for the vampire to burn up?) don’t detract from what a sweeping and accessible crowdpleaser it is. Coogler may not have been able to do his best work when trapped within the machine of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but with “Sinners,” he proved himself capable of making a big-budget, high-concept genre film staked on original ideas. It’s only a matter of time before there are dozens of films trying to replicate the success of “Sinners.”

7. “F1”

2025 saw a year where Hollywood’s commercial blockbusters were in crisis, as “superhero fatigue” began to set in, and casual audiences showed how terrible their taste could be by making cynical cash grabs like “Lilo & Stitch” and “Jurassic World: Rebirth” into massive hits. There’s an important role that monocultural event cinema can have, and no one has defined the past few decades of blockbusters quite like Jerry Bruckheimer, whose career is built on the concept of putting the work on the screen.

When paired with Joseph Kosinski, the energizing young filmmaker who revitalized ‘80s nostalgia with “Top Gun: Maverick,” Bruckheimer crafted the type of summer movie that simply isn’t made anymore. Beautifully shot in a way that continuously pushes the technical precision of the medium forward, “F1” is a shot of adrenaline that single-handedly justifies the existence of premium format theaters.

There’s a difference between being “generic” and being “familiar,” and “F1” leans into the classic trope of a multi-generational partnership learning from one another. Retired racing legend Sonny Hayes (Brad Pitt) is looking to have the last ride of his career, whereas the up-and-comer Joshua Pierce (Damson Idris) is ready to secure his own future.

The magnetic chemistry between these two charismatic stars adds enough propulsion to power some of the most visceral, exciting racing scenes ever filmed, which is only heightened by one of Hans Zimmer’s best scores in ages. When the phrase “they don’t make ‘em like that anymore” is used, “F1” is the prime example that proves that yes, they in fact do.

6. “Train Dreams”

“Train Dreams” is a lyrical, existentialist cinematic poem about the faith and futility of one man’s life, filtered through the journey of America’s industrial revolution. Although such a painterly, thematic approach to larger-than-life issues could have made Clint Bentley’s adaptation feel emotionally opaque, the screen is illuminated by Joel Edgerton in one of the best performances of his career.

Edgerton has been one of the most underrated actors of his generation for well over a decade, and “Train Dreams” is one of the rare instances in which he is at the center of the frame. To have cast a bigger star would betray the film’s themes, as his character Robert Granier is intended to be passive and occasionally helpless as he watches the radical ways in which his nation dismisses its naturalistic environments.

“Train Dreams” may not have the same complexity as its source material, as some of the racial and political subtext is reduced to more observational instances, rather than any insight as to what Grainier did to either protect or challenge the status quo. That being said, the vignette-style simplicity of the film’s construction makes it a powerful viewing experience because there is no suggestion that Bentley is rushing towards a conclusion.

There are heart-stirring moments, but they emerge because of the film’s authentic portrayal of mortality, and not from some hackneyed attempts to be a tearjerker. It’s impressive that the Oscars were able to reward a film so subtle and understated, particularly one that (because it debuted on Netflix) has not been widely seen in its intended format.

5. “Bugonia”

While “Bugonia” marks a reunion for Yorgos Lanthimos with two of his most beloved English-language stars, the film lacks the heightened, playful satire of works like “The Favourite” and “Poor Things.” Lanthimos returned to his roots for a deeply disturbing, yet frequently hilarious examination of an unwavering sickness within contemporary society, where those with power have no means of serving others.

The power dynamics between the conspiracy theories-obsessed Teddy (Jesse Plemons) and the prominent CEO Michelle Fuller (Emma Stone) couldn’t be more oblique. He may have literally stripped her of dignity, resources, and safety, but he’s still fighting a losing battle on behalf of every ”second-class” citizen whose livelihood has become trivialized by the powers that be.

The friction between these two characters is, at times, hilarious in a way that Lanthimos hasn’t been in years. Teddy is a character whose reasoning and precision are only unusual because of his absurdist conclusions, and Michelle’s greatest fault is that she’s trying to use corporate-speak persuasive techniques against someone who’s already convinced she’s the enemy.

It’s a film that gets sadder and eerily authentic as it goes forward, revealing the latent reasons why these two characters have come head-to-head. Plemons brings a remarkable degree of empathy to a character whose pain could have easily been played for satire, and Stone swings for the fences with one of her bravest performances yet. “Bugonia” can’t be easily classified as a drama, a farce, an adventure, a work of horror, or a parody, but it’s reflective of the current moment in a way that few contemporary films have been.

4. “The Secret Agent”

It wouldn’t be inaccurate to describe “The Secret Agent” as an espionage film, but it’s certainly not the “Mission: Impossible”-style adventure that its title may have suggested. Rather, Kleber Mendonça Filho’s rousing political drama explores the livelihood and perseverance of the Brazilian people during the 1970s, in which the brutalistic military regime divided and preyed upon the weak.

The film suggests that retaining one’s values and simply living in defiance of totalitarianism is an act of rebellion in its own right, and that to engage in the type of “mischief” that the title refers to is a form of spycraft in its own way. “The Secret Agent” is composed of vignettes and half-truths, but it comes together as a kaleidoscopic collection of fruitful memories, which are preserved within the film’s moving final moments.

Although there’s no instance in which the real pain endured by Brazil’s people is trivialized for the sake of entertainment value, “The Secret Agent” often feels like a “hangout movie” as much as it does a thriller. Wagner Moura’s career-best performance as the former professor Armando embodies the ways in which a common citizen can rise to the expectations of the moment without sacrificing his individuality.

Whether it’s a funky car chase, an amusing tall tale, or a thrilling shootout, “The Secret Agent” moves with the momentum of a film that’s of the moment and isn’t weighed down by nostalgia. It’s not just a complex, representative exploration of the facets in politics and culture that defined a specific moment in history, but a downright exhilarating feat of entertainment.

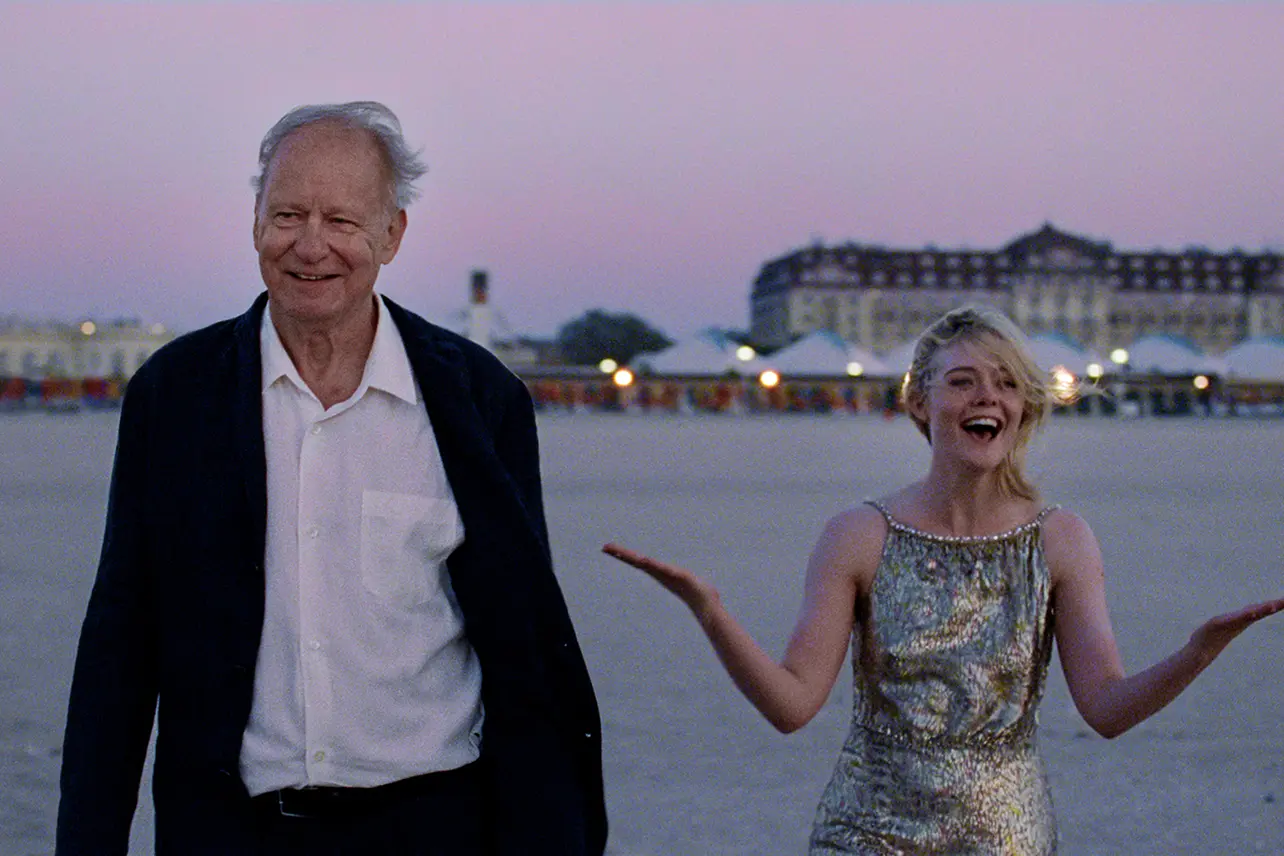

3. “Sentimental Value”

“Sentimental Value” both feels similar in style to classic Oscar winners with the “family drama” genre (such as “Ordinary People” or “Terms of Endearment”) and a bold, unknowable work of experimentation that feels far too niche for the taste of Academy voters. Although it’s a portrayal of a dysfunctional family that unpacks generational grief, “Sentimental Value” doesn’t congeal itself around tearjerking monologues or attempt to simplify its complex emotional issues with simple truisms.

It’s a portrayal of how it is within the nature of parents to pass along qualities, both good and bad, to their children, and how falling down the same route of conflict is almost inevitable. Although there are instances of dark humor and empowering clarity throughout “Sentimental Value,” there’s no moment in which Joachim Trier sacrifices his authenticity for the sake of dramatic convention.

Renate Reinsve, who gave her breakout performance in Trier’s previous film “The Worst Person in the World,” is given a more challenging task in playing a prickly, emotionally closed-off character whose inability to ask for help could have been grating if the pain didn’t feel all too real.

Stellan Skarsgaard has a similarly difficult task in playing an absent, overbearing father whose desire for redemption feels earned because of the torment within his own past. “Sentimental Value” is a much more dynamic and ambiguous film than it could be given credit for by those who only watched it once, and it’s a minor miracle that the Oscars were able to recognize a work of art that doesn’t feel the need to announce its own greatness.

Also Check Out: 8 Movies Like “Sentimental Value”

2. “Marty Supreme”

“Marty Supreme” is set in the ‘50s, styled off the New Hollywood era of the ‘70s, released in the ‘20s, but charts an exploration of the American dream that has existed since 1776. The film is about how the “Land of Opportunity” became dominated by industry, and how the pillars of infrastructure and capitalism gave those with any sense of self-worth the desire to break from their castes.

Marty Mauser (Timothee Chalamet in a career-best performance) is driven by ego and a desire for legacy, which paints him into a corner when capitalism is seen as the only route to success. He’s a destructive, obnoxious protagonist who burns nearly every bridge in his path, but it’s hard not be swept away by his very specific goals of being world-renowned. As scattershot as it may seem, “Marty Supreme” has intentionality behind each of its wildest moments.

That “Marty Supreme” isn’t really about ping-pong is a feature, not a bug, as the notion of being distracted and dismayed within the process of reaching one’s lifelong endeavor is a tale as old as time. Josh Safdie finds a way to turn every minor set piece in “Marty Supreme” into an immersive and creative detour, all whilst charting the various ways in which Marty has wreaked havoc upon the lives of those who either purposefully or inadvertently stepped in his way. Whether it should be seen as a rousing, triumphant success story or a deeply cynical tragedy, “Marty Supreme” is as genuinely jaw-dropping and painstakingly made as any American film in recent memory.

1. “One Battle After Another”

Rarely has a film been so unanimously hailed as the year’s best as “One Battle After Another,” as Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest masterpiece blew all other 2025 contenders out of the water. It’s a film that’s set in an alt-present that examines the ways in which America crumbled into an embittered, stagnated society, all whilst passing the torch from unsuccessful rebels of a previous generation to the activists who actually might make a difference.

The father-daughter story is as rich and personal as anything Anderson has written, but “One Battle After Another” is also a thrilling masterclass in action that features more exciting, visceral, and pulse-pounding chases and shootouts than any of the superhero films of the year. Even if every single still could be taken out and viewed as a gorgeously rendered image, there’s a momentum to “One Battle After Another” that makes its nearly three-hour running time fly by.

Leonardo DiCaprio proves once again that he’s at his best playing well-meaning, goofy losers with hearts of gold, and there’s a maturity to his paternal instincts that makes Bob Ferguson more than the butt of a joke. Chase Infiniti’s breakout performance is not only the discovery of the year, but a bracing portrayal of the burdens felt by a generation taught that they have no room to grow.

Sean Penn’s terrifying, if wacky, performance as Colonel Lockjaw is perhaps the best screen villain since Christoph Waltz’s Colonel Han Landa in “Inglourious Basterds,” and that’s all without mentioning the great supporting work by Benicio del Toro, Regina Hall, and Tony Goldwyn. Anderson has long been overdue for an Oscar, but “One Battle After Another” would be rewarded for its standalone achievements, and not just as a makeup victory.