The Boy and the Heron (2023) Movie Review: In her recent feature Petit Maman (2021), film-maker Céline Sciamma drew inspiration from Hayao Miyazaki for a story sprinkled with magical realism, where a young girl befriends another, that we later discover is a much younger version of her own mother. Through a growing friendship between the two kids, the young girl is able to better connect with and understand the more adult version of her mother.

In many interviews, Sciamma has clearly stated that Miyazaki and Japanese anime, including Studio Ghibli films like Princess Mononoke (1997) and My Neighbor Totoro (1998), among others, were a massive influence on her film. Not only did Sciamma follow a mantra – WWMD (What Would Miyazaki Do?) – whenever she felt stuck while making Petit Maman, the film was originally intended to be an animated one that people would take their kids to – the kind of rare animated feature that is aimed at kids and adults alike.

It’s no surprise, then, that back in 2021, when Petit Maman released, in the absence of a new Miyazaki feature film for almost a decade (he had announced retirement, claiming that the short film Boro the Caterpillar (2018) would be his last work), Sciamma’s take on Miyazaki felt like a gift to the world. This was the closest we’d get to a new Miyazaki film that wasn’t made by Miyazaki himself.

You cannot imagine my delight – and I’m sure this delight was shared by millions of Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki fans – when Miyazaki announced he was once again coming out of his self-proclaimed retirement for a new animated feature. He’s ‘unretired’ himself numerous times before, with one of the most significant reasons being that Studio Ghibli doesn’t seem to have an obvious successor apart from Miyazaki, and at this point, Ghibli and Miyazaki are perhaps forever inseparable.

This new feature, as announced by Miyazaki, turned out to be The Boy and the Heron (2023), based on a 1937 novel ‘How Do You Live?’ by Genzaburō Yoshino. Incorporating fantasy and magical realism elements that are trademarks of Miyazaki’s touch, the film traces the journey of a young boy named Mahito, whose mother is tragically killed in a fire accident. Unable to come to terms with the grief of losing his mother, he is lured into an alternate magical realm by a heron-like creature who assures him that his mother is alive and well.

The reason I started with Petit Maman is because once you’ve experienced The Boy and the Heron, you cannot help but smile at the mutual admiration that Sciamma and Miyazaki show each other in their most recent works: Sciamma started out trying to make a film that captured Miyazaki’s style, and by some beautiful cosmic alignment, Miyazaki’s latest film – at the core of it all – is a sibling to Sciamma’s. Both films are inexplicably tied together by this throughline of a young child processing their grief and accepting the hand that fate has dealt through the promise of a fantastical meeting with their mother when she was also of a similar, youthful age. Sciamma ended up making a film that had a touch of Miyazaki, and Miyazaki returns the favor with his film that has a touch of Sciamma.

The Boy and the Heron was originally titled ‘How Do You Live?’ borrowing from the title of the novel on which it is based. While the film’s title was changed for English-speaking territories, it retains its original title in the Japanese version. I saw the original Japanese version with English subtitles, and it will be interesting to compare how the English dubbed version differs, if at all. With Robert Pattinson, Mark Hamill, Christian Bale, and Willem Dafoe leading the English dubbed voice cast, it’s a red carpet of heavyweights that’s been laid out when it comes to dubbing the film in English. Irrespective of the English dubbing, it’s helpful to make a note of the original title of the film. ‘How Do You Live?’ is more accurately reflective of the contemplative mood that this film wants its viewers to slip into.

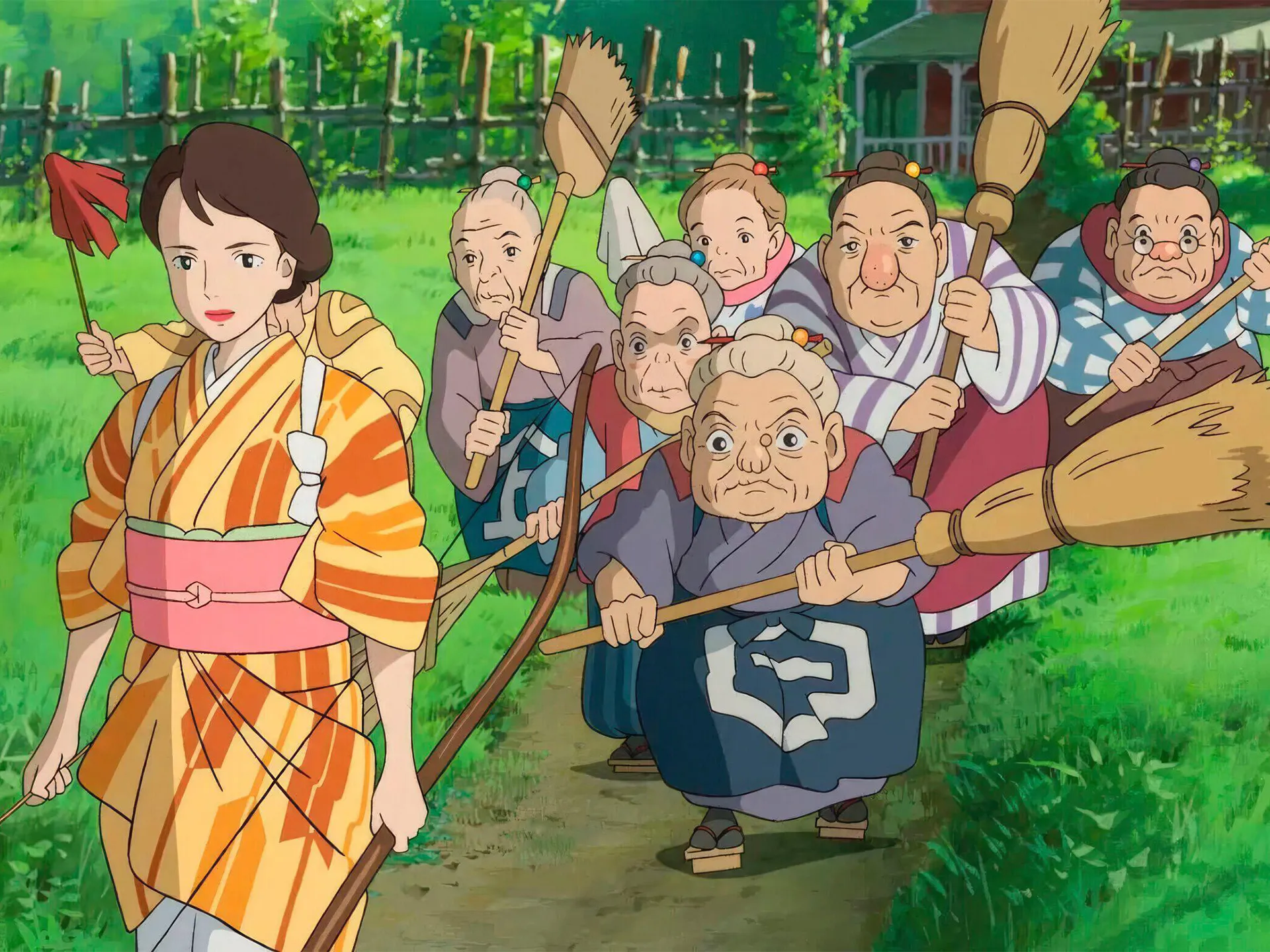

From the very first sequence, where we see Mahito running towards the hospital on fire where his mother works during the Pacific War, there’s an awareness that this film has a darker undertone, much like the darker tonality embedded in Miyazaki’s other works, such as Princess Mononoke and Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), as opposed to some of his ‘frothier’ films such as My Neighbor Totoro (1988). The entire opening sequence is a stunning example of the imaginative fluidness of Miyazaki’s world-building that comes alive through the form of hand drawn animation and is worth the price of admission alone. The mass of people and the commotion that ensues as the fire rages on is shown as ghostly silhouettes that blend into each other, indistinguishable visages that Mahito must wade through as he searches for the one face that he is looking for: his mother’s.

Miyazaki’s latest offering feels personal and autobiographical, especially given his own relationship with his mother and her health issues while he was in his formative years. From the late 1940s to the mid-1950s, Miyazaki’s mother battled Pott’s disease and had to be nursed from home. There are other clues in the film that indicate that the character of young Mahito is perhaps closely based on young Miyazaki himself: much like Mahito, Miyazaki’s family had to move away from Tokyo to a rural area for safety to escape the impact of war when he was just a toddler. Just like Mahito’s father in the film, Mizayaki’s father also worked in manufacturing, running a business that produced airplane parts.

Thanks to a sprinkle of magical realism and how Miyazaki blends fantasy with reality, you can extend this autobiographical thread to read this film as Miyazaki fondly looks back at his own body of work that he’s created, and not just his early life. In the film, Mahito goes on a transformative journey to another magical realm and, in the process, discovers something more about himself. This idea is remarkably similar to Miyazaki’s earlier film Spirited Away (2001), where a child travels to another world, but the external journey is indicative of the inner journey towards acceptance of one’s fate that needs to occur.

The magical realm in The Boy and the Heron is inhabited by cute, spirit-like creatures called the ‘Warawara’ that float up above into the sky to eventually be born in the real world. The design of the Warawara reminds you a lot of the ‘Kodama’ – the tree spirits from Princess Mononoke. In the magical realm, the lines of the ‘undead’ rowing boats are reminiscent of the planes and planes full of the dead in Porco Rosso (1992). And I could go on and on. For Miyazaki fans, this film will give you so much satisfaction upon rewatches, allowing you to find numerous easter eggs that he’s interspersed throughout the film that refer to his extensive oeuvre.

Apart from some truly magnificent flourishes of hand-drawn animation (that we’ve come to expect from Miyazaki), the film also pleasantly surprised me in some other technical areas. The Boy and the Heron have some of the best foley sound work that I’ve heard in a film this year. From the sound of a heron flapping its wings to the difference between heavy and light footsteps, the precision in sound design enhances your interaction with the world that’s created on screen. If this doesn’t at least get a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Sound, then you’ll find me at a bar drowning myself in shots of whiskey.

Longtime Miyazaki collaborator Joe Hisaishi returned to provide the musical score of this film. The Original Soundtrack (OST) consists of 37 tracks, and I cannot separate the skill of the animation from the superlative musical score. For example, I don’t think I would be bawling my eyes out in the scene where Mahito finds a copy of the book ‘How Do You Live?’ that his mother left for him if it wasn’t punctuated by the piano score called ‘Mother’s Thoughts’ by Hisaishi. Conversely, in one of the few lighter moments in the film, when we’re introduced to the Warawara, Hisaishi’s use of ‘Warawara’s Theme’ does immense work in uplifting the mood momentarily in what is otherwise an emotionally heavy and mostly sad film. I’m glad to see that Hisaishi and The Boy and the Heron have been shortlisted for Best Original Score at the upcoming Academy Awards.

And what of this magical realm? If we extend the autobiographical reading, one way to read the film is to interpret that the magical realm is a stand-in for Studio Ghibli, and the creator of this realm is Miyazaki himself. One of the ideas that the film builds upon is that the magical realm is unsustainable, it cannot go on existing for eternity. Whether it is Mahito – who came in search of his mother – or other numerous creatures that inhabit the realm, one day, they will all have to leave that realm and join the real world. It’s an inevitability that can only be delayed, but there’s no escaping from it.

The unsustainable nature of the magical realm in the film mirrors the anxieties for the future state of Studio Ghibli once Miyazaki is gone. Miyazaki is 82 years old now. Earlier this year, Japanese broadcaster Nippon Television bought a controlling stake in Studio Ghibli, with 42.3% of shares in the company. For a while, there were rumors that Disney might acquire it, which didn’t come to pass. Regardless, change seems inescapable and just around the horizon, and Miyazaki appears to be acutely aware of it. In the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (2013), when Miyazaki is asked if he’s worried about the future of Studio Ghibli, he responds with an air of inevitability. “The future is clear,” he says. “It’s going to fall apart. I can already see it. What’s the use of worrying? It’s inevitable.”

But you don’t have to read The Boy and the Heron as a semi-autobiographical parable of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli for it to work its magic. The film has a universality that will strike a chord in your heart irrespective of your interest in or knowledge of Miyazaki’s life. When you strip away its layers, the film strikes an interesting balance of bleakness and hope. The film presents an incredibly bleak picture of the present, where no world is safe or comforting. The magical realm, where everything is supposed to be perfect, contains fascist forces ruled by a dictator, Parakeet King, intent on wreaking havoc in a bid to take control. The real world, which Mahito escapes because it’s riddled with war and reminds him of the loss of his mother, is no refuge either. This is, arguably, Miyazaki’s bleakest film yet.

And still, when Miyazaki casts his eye to the future, to the next generation, he maintains a hopeful stance. Much like the Tower Master, who controls the magical realm and places his faith in the young Mahito to make his choice about his future, Miyazaki believes the next generation will make choices that will usher in change for the better. The film is an indictment of the current generation that has made choices that have only led to war, destruction, and an unsustainable way of life. However, Miyazaki has faith that the next generation will not make the same mistakes.

With the younger generation today having to live through a pandemic, cost of living pressures, climate crisis, and being part of a world that seems eternally at war, the current generation hasn’t left a world that appears sustainable enough for the upcoming generations to enjoy. Miyazaki pulls no punches in accepting how despairing our reality truly is. But what of the future? Can we conjure up enough magic to make ourselves believe it’ll be better than our present? It will take more than one Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli for that miracle…

![Wade [2020] Short Film Review: A Delicate, Detailed Horror Story about Climate Crisis](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/WADE-SHORT-FILM-highonfilms-2-768x577.jpg)

![Ibrahim: A Fate To Define [2019] ‘TIFF’ Review: Was it a storm or was it an axe that brought the tree down?](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Ibrahim-A-Fate-to-Define-TIFF-768x384.jpg)

![The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez [2020] Netflix Review – A Shocking Case of Child Abuse, Murder and Institutional Negligence](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/The-Trials-of-Gabriel-Fernandez-2020-768x432.jpg)