Fake gods sentenced to the gallows. Opening film at the 77th Locarno International Film Festival, “The Flood” (Le Déluge), is a historical drama directed by Italian filmmaker Gianluca Jodice, his second feature film. It is 1792, the apex of the French Revolution and the year of the foundation of the First Republic.

In a spacious hall with a checkered floor, disassembled pieces of furniture, drab and baroque, are improvised to welcome some emeritus guests. We are in the Tour du Temple Prison on the outskirts of Paris, and the guests in question are none other than the remnants of the French crown. Louis XVI (Guillaume Canet) is holding a cane and is dressed in gold brocade. The consort, Marie Antoinette (Mélanie Laurent), in silver and white. There are two children, Marie-Thérèse and Louis-Charles, and there are some court servants. Gathered together, waiting to be judged by the people who deposed them. The beginning of a captivity and incipit of the film. As claimed by the director, “Le Déluge” indeed begins where many other films would eventually end, in the suspended moment between a spectacular fall and an equally spectacular condemnation.

Structured as a triptych, Jodice’s film depicts the former royals shedding their divine personas, adopting the guise of ordinary people, and finally being stripped of even that identity when judged as fallible humans. Actually, the director’s narrative and psychological insight are, on paper, extremely interesting. What does a fallen king feel? Considering the divine conception of the monarchy of the time, what does a fallen god feel? Anger, sadness, shame? Regret? Remorse? What about a queen, a court goddess? What does it mean, for power incarnate, the ridiculousness of being submitted to those who should be, by the law of nature, beneath? It must be a unique point of view, the fall from the summit of the world.

Unfortunately, it is precisely upon execution that “Le Déluge” stumbles and, like his subjects, collapses. Jodice’s royals are, superficially, average humans subjected to unfair treatment, bewildered by the (cinematically abused and here trivially emphasized) difference, material, between glitz and squalor, squalor that is nothing more than the everyday life of the common folk. There is little availability of clean clothes, frugal food, expropriation of property, and constriction in small spaces. Only one servant remains, Cléry (Fabrizio Rongione), from whose diaries the entire film is inspired.

In this portrayal, Louis XVI, “King of the French,” seems to find himself in the Tour de Temple by misunderstanding, hinting at his role of “divine emissary” as a popular necessity, a concept never really developed by the narrative. Marie Antoinette is portrayed as a dignified, pitiful, fragile woman, and overall, the movie appears almost oblivious to why its characters find themselves confined in the first place. That is, not to be punished, but to be judged. And it is bizarre because while it is a clear directorial choice not to pass judgment, it is a lack, in what should be a film devoted to introspection, the staging of a chorus of characters seemingly unaware of their own – massive – faults.

The choice of representation of the monarchy as “people like any other” and therefore worthy of empathy is reasonable but not sufficient as the univocal point of view of the narrative, also in light of the negative conception with which the rest of the people, a barbaric mass lacking the so-calculating dignity that distinguishes royalty, is brought to the scene.

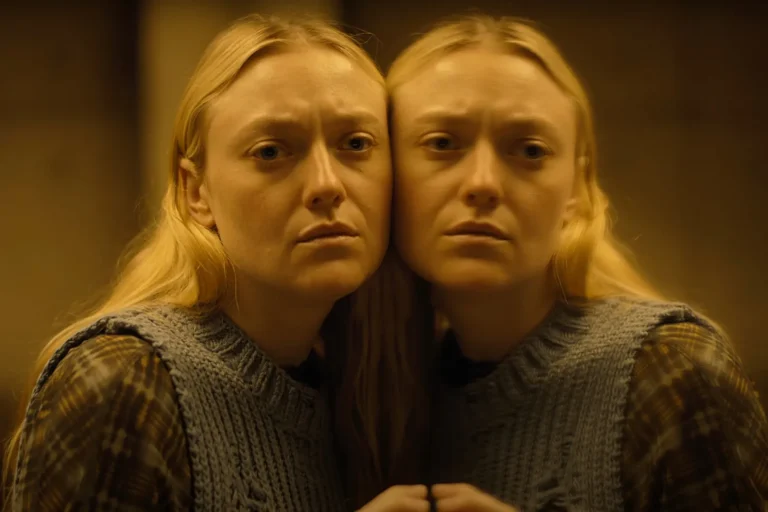

The screenplay, written by Jodice in collaboration with Filippo Gavino, does not help, as the artificiality of the dialogue exacerbates the feeling that the “unveiling of the facades” promised by the film is never really achieved. Still, the acting performances, particularly of the two lead actors, remain good. Guillaume Canet, subjected to heavy prosthetic makeup, is able to give Louis the humanity required by the film, and he stars in some of the film’s most successful sequences. However, the reduction of the character to a weak and passive personality, ignoring his responsibility as ruler of a nation, seems inadequate. Mélanie Laurent elegantly inhabits the role of Marie Antoinette despite the two-dimensionality of the character’s writing, and there’s an attempt to compensate with some perhaps over-the-top acting.

Visually, “Le Déluge” is a very beautiful movie, particularly the cinematography by Daniele Cipri and the sets by Tonino Zera. Derivative of an aesthetic somewhere between Lanthimos’s “The Favourite” and Peter Greenaway’s films, some scenes have a pictorial delicacy and composition. Among the most noteworthy elements are the splendid costumes made by Massimo Cantini Parrini, here trimmed to the finest detail and beautifully captured by the camera.

“Le Déluge,” on the whole, is a finely directed wasted opportunity. The film’s potential to offer a fresh perspective on the French Revolution is undermined by both the director’s vague and unclear message and the superficial portrayal of the characters. Seemingly the product of pure historical speculation and limited by the partial point of view of the document from which it is based, Jodice’s film thrives on an interesting premise debased by an execution that is as simplistic as it is overly biased.

![The Manor [2021] Review : Barbara Hershey’s lead performance is not enough to save this hurried entry into Welcome to the Blumhouse series](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/The-Manor-Movie-Review-1-768x513.jpg)

![Café Society [2016] : Of Unfulfilled Romances and Regrettable Life Choices](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/cafe-society2.jpg)

![The Last Movie Stars [2022] ‘SXSW’ Review: Ethan Hawke’s Tribute To Paul Newman And Joanne Woodward](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Last-Movie-Stars.webp)