Science fiction movies are rarely about science. In fact, the ostentatious CGI-dependent, invasion-centered storylines we are repeatedly subjected to strictly restricts the sci-fi genre. A lot of sci-fi features exist completely outside the realm of scientific possibility that it belongs to the fantasy genre. Still not all such fantastical story elements culminate in clichéd post-apocalyptic narratives with vapid action. For some, though the emphasis on scientific accuracy is tenuous, science-fiction genre can be a tool for social criticism. Just like how fairy-tales withholds undeniable truths in it, sci-fi could perfectly channelize the collective nightmares of a society in the form of allegory or parable. It is probably why the golden age of Russian science fiction was the Soviet era, which explored sociopolitical concerns of the time through fanciful plots, and thereby evading strict censorship. Georgiy Daneliya’s late-Soviet era madcap sci-fi Kin-dza-dza! (1986) belongs to this tradition of sci-fi, i.e., utilizing distant worlds to present the satire of contemporary society.

In the age of space race, science-fiction literature and movies directed towards youth population disseminated the ideas of space travel, technological advancements, and contact with alien race. Space became the final frontier. Hence, writers and film-makers rushed to conquer it. From Destination Moon (1950) to Star Wars (1974), Hollywood films have imagined a utopian space-conquering human race, freed from earthly concerns though often engaged in the same internecine conflicts. Soviet sci-fi films of the 1960s, though not as well known as their American counterparts, made similar storylines while also creating an outlet for their own ideologies.

Related to Kin-dza-dza! – 12 Monkeys [1995] Review – An Intriguing Dystopian Tale by a Masterful Fantasist

As the years passed, the sci-fi authors took a more critical approach pertaining to the utopian views of future. The Strutgatsky brothers were one of the important novelists of the time whose parallel worlds starkly resembled the real world. Their novels Roadside Picnic (Stalker) and Hard to be a God were efficiently adapted into movies. But then there were authors like Philip K. Dick, Kurt Vonnegut, and Stanislaw Lem whose outlandish and wickedly funny tales had broader concerns and bestowed deeper truths. Novels like Slaughterhouse-Five or Solaris didn’t just try to engage with political and social issues of the era, but also recognized the absurdity inherent in the human condition. Daneliya’s Kin-dza-dza! reminded me of Vonnegut and Lem (think of Ijon Tichy series) with a bit of cyberpunk elements thrown in. Furthermore, movie buffs can probably relate to this description of Kin-dza-dza!: ‘Mad Max meets Monty Python’.

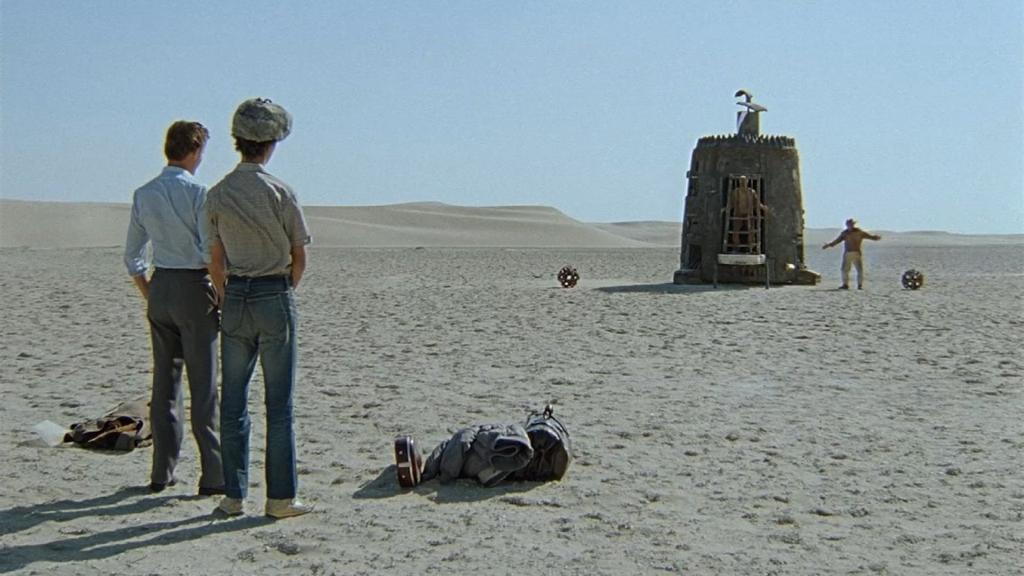

Written by Daneliya and Revaz Gabriadze, the plot is set up with deadpan humor and matter-of-factness. During a mundane grocery run, Moscow foreman Vladimir Nikoalaevich (Stanislav Lyubshin) comes across a young Georgian named Gedevan (Levan Gabriadze) who asks him to help a strange shoeless man (standing in the harsh winter) claiming that he is from another world. Vladimir and Gedevan approach the man. The stranger presents a ‘translocation device’ and enquires about the ‘number of this planet in the galaxy spiral’. Perceiving the stranger as a homeless madman, Vladimir aka Uncle Vova disdainfully presses the device. In the blink of a second, the two are teleported to the desert planet called Pluk of Kin-dza-dza galaxy.

Uncle Vova’s instant pragmatism and dry wit as he tries to navigate Pluk and find the means to get back to Earth is one of the many pleasures in Kin-dza-dza!. It’s hilarious when Vova believes that they must be within USSR borders. During the long walk through the desert, the two come across a flying contraption that resembles a large-size rust bucket than a spaceship. Two (humanoid) inhabitants of Pluk emerge from it, and engage in bizarre antics which don’t make any sense. The two are actually local artists named Uef (Evgeny Leonov) and Bee (Yuriy Yakolev). The vocabulary in the planet is almost restricted to a single word: Koo. To express anger, frustration, and similar emotions, they use the socially accepted expletive: Ku!

After rummaging through the handful of items Vova and Gedevan have on them, the two ‘aliens’ ditch them at the first opportunity. However, when Vova lights up a cigarette, Uef and Bee return back, excitedly pointing at the matchbox, calling it ‘Ketse’. It turns out that a box of matches is the most precious item on Pluk, and it might provide them the ticket back to Earth. Kin-dza-dza! unfolds in a very episodic manner, rationing out small yet pivotal information about Pluk’s social hierarchy. Therefore, it might take some time to get used to the restricted Plukanian vocabulary and its social environment. Soon, it’s also revealed that the humanoid alien race is telepathic. After poking about the Earthlings’ mind, the Plukanians talk in fluent Russian. What unfolds are humorous and wacky mini-adventures through the ecologically drained Pluk.

Good satires possess the kind of humor that has universal appeal. Though Kin-dza-dza! would be lot more hilarious if you know something about this particular time in Soviet Russia, the prevalent comic absurdity in the narrative isn’t dated in anyway. Made in the year of perestroika and glasnost, Kin-dza-dza! is ostensibly a look at the then-disintegrating Soviet Union, endangered by increasing political and economic instability. In one of the scenes, the telepathic Plukanian says, “What kind of an idiot would be thinking the truth on Pluk”, which is a commentary on Soviet authoritarianism, and even the existence of such a dialogue in the previous decades would have drawn the ire of censors. More radical was the humor pertaining to the deification of the planet’s leader.

Nevertheless, Daneliya’s at times isn’t specific to Soviet society. The underground factory where large numbers of workers toil for a trivial purpose or the environmental destruction of Pluk in the name of progress are as eerily relevant as it was in the 80s. The egregious racism directed against the Earthlings – a dominant aspect in societies across the world – in the narrative brims with irony. A race powered by interstellar flights and telepathy has rationalized hierarchy based on ‘color’. Even though the water is scarce and people are living underground, the march for ‘progress’ persists on Pluk. A planet that’s indifferent to ecocide but passionately defending absurd hierarchies! Yes it sounds very familiar.

Also Read: 10 Best Time Travel Movies Ever Made

The use of matchbox as the all-important currency in Kin-dza-dza! has its relevance in the Soviet culture. For Soviet people, collecting matchbox labels was one of the favorite hobbies from late 50s to 80s. For decades, Soviet Union was also a leading exporter of match boxes. Touted to be the best in the world, matchboxes are frequently referred to in Soviet popular literature and movies. Moreover, the officials used matchbox labels for propaganda, to advertize goods, and during the Space Age there were space-themed labels. A lot of safety match labels from the Soviet era can be googled, and what you’d witness is some of the stunning and elegant graphic designs.

Probably like all the things that degraded in Soviet Union in the later decades, the quality of matchboxes too became disputable. In Jillian Porter’s brilliant essay, the symbolism of matchbox in the film is spelled out clearly: “Kin-dza-dza! relies on the much-vaunted yet publically derided value of this staple commodity to poke fun at the scarcity of state-produced goods and the failure of Soviet science and industry to reach the grand goals of the Revolution.” [1] But pardon me if what I have written so far makes Kin-dza-dza sounds like a somber discourse on Soviet Russia. It’s definitely much more than that. It is truly unique yet easily accessible and dispersed with ethical and moral concerns which keep us engrossed in Vova & Gedevan’s survival. Even the comically self-absorbed aliens – Uef and Bee – extract our sympathy by the end.

Kin-dza-dza! was made on an unbelievably low budget with things readily available and shot mostly in the desert (in Turkmenistan). The elaborate sets for the film were lost in shipping. Nevertheless, the sparseness utilized to build Pluk adds to the crude aesthetics of the narrative. There is an animated version of the story, which was made in 2013 and whose storyline is somewhat different than the original.

Watch the full movie on YouTube:

To discover more such hidden gems of Russian and Soviet Cinema please visit: Russian Film Hub

Note:

- Simultaneous Worlds: Global Science Fiction Cinema – Alien Commodities in Soviet Science Fiction Cinema, Jillian Porter, University of Minnesota Press, 2015

To read more about Soviet Sci-Fi Cinema:

Soviet Sci-fi Film and Different Modalities of Future Ecosystems

Soviet Sci-fi: The future that never came

![Halloween Kills [2021] Review: Adds nothing of value to the franchise lore](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Halloween-Kills-768x512.jpeg)

![The Fifth Horseman Is Fear [1965] – A Unique & Timeless Take on Fascist Tendencies](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/The-Fifth-Horseman-is-Fear-1965-768x432.jpg)

![Encounter [2021] Review: Riz Ahmed takes the Spotlight in this Sci-fi thriller](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Encounter-2021-768x432.jpg)