The Academy Awards, or the Oscars, are one of the most prestigious honors in the film industry. While millions tune in each year to watch Hollywood’s biggest stars celebrate cinematic excellence, there are plenty of intriguing behind-the-scenes facts that even die-hard movie lovers might not know. Here are ten surprising pieces of Oscar facts that should blow your mind:

1. The Stolen Oscar Heist

In 2000, just days before the Academy Awards, a shipment of 55 Oscar statuettes was stolen from a loading dock in Los Angeles. The disappearance of the trophies sparked a major investigation involving local law enforcement and the FBI. After an extensive search, 52 of the stolen Oscars were found discarded in a dumpster behind a Koreatown grocery store by a man named Willie Fulgear, who later received a $50,000 reward for his discovery. However, three statuettes remain missing to this day, making them some of the most sought-after lost artifacts in Hollywood history. The incident prompted the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to implement tighter security measures, including improved tracking systems and stricter transportation protocols, to ensure that such a theft never happens again.

Read More: The Great Oscar Heist: How 55 Statuettes Disappeared Before the Big Night!

2. Walt Disney Holds the Most Oscars Ever

The legendary Walt Disney remains the most awarded individual in Oscar history, winning 22 competitive Academy Awards and receiving four honorary ones. His first win was in 1932 for the animated short Flowers and Trees.

3. An Oscar Winner Sold His Trophy for $1

In 1992, Harold Russell—the WWII veteran who stunned Hollywood by winning two Oscars for his poignant role in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)—made headlines again, but this time off-screen. Facing financial strain, he consigned his Best Supporting Actor statuette to Herman Darvick Autograph Auctions. On August 6, a bidding war erupted in New York City, culminating in a private collector securing the trophy for $60,500. Russell insisted the sale funded his wife’s medical care, calling it a “necessary sacrifice,” though skeptics later questioned his motives, hinting at murkier fiscal woes.

The transaction split public opinion. While pre-1950 Oscars weren’t subject to the Academy’s resale restrictions, Russell’s choice—a war hero auctioning his legacy—felt jarringly un-Hollywood. Purists decried the commodification of art; sympathizers rallied behind his vulnerability. The Academy, rattled by the spectacle, doubled down on its ethos: post-1992, winners were formally barred from profiting off their statuettes without first offering them back to the Academy for a symbolic $1.

Russell’s Oscar now resides in obscurity, its gleam untarnished but its story layered with contradiction. Was it a loving act of desperation or a pragmatic surrender? Decades later, the statuette stands as a relic of both cinematic history and human frailty—proof that even gold can’t outshine life’s tangled, unscripted truths.

4. A Ventriloquist Once Won an Oscar

In 1938, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen received an honorary Oscar for his contributions to film. But here’s the twist—the Academy gave him a wooden Oscar statuette, fitting for a man famous for his wooden dummy, Charlie McCarthy.

5. The Youngest Oscar Winner Was Just 10 Years Old

At just 10 years old, Tatum O’Neal made history as the youngest-ever Oscar winner, taking home Best Supporting Actress for her role in Paper Moon (1973). Starring alongside her real-life father, Ryan O’Neal, she delivered a performance so sharp, witty, and emotionally resonant that it outshone even seasoned actors.

Playing Addie Loggins, a street-smart orphan who teams up with a con man during the Great Depression, O’Neal captivated audiences with her natural charisma and undeniable talent. Her win remains unmatched in competitive acting categories, cementing her as an Oscars legend.

However, her journey post-Oscar was anything but smooth. She faced personal struggles, family conflicts, and the challenge of transitioning from child stardom to an adult acting career. Still, her Paper Moon performance stands as one of Hollywood’s most extraordinary debuts—proving that, sometimes, the youngest stars shine the brightest.

6. Only Three Movies Have Ever Won the “Big Five”

Winning an Oscar is already a feat, but only three films in history have swept the “Big Five” categories: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Screenplay. These films are:

- It Happened One Night (1934)

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

- The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

7. Marlon Brando Rejected His Oscar

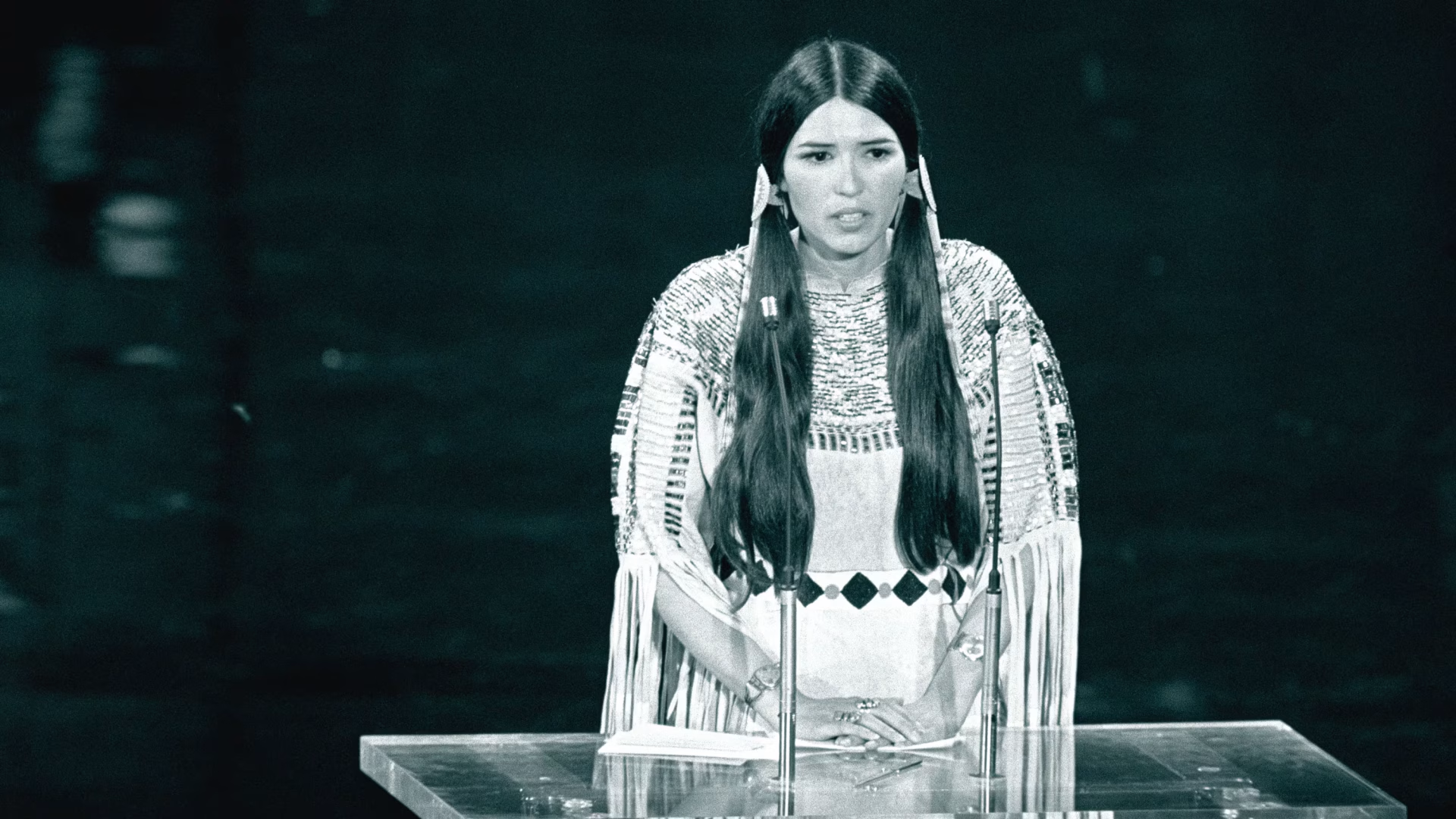

On March 27, 1973, the Oscars witnessed an unprecedented act of rebellion. When Marlon Brando’s name was announced as Best Actor for The Godfather, the audience erupted in applause—only to fall silent as Sacheen Littlefeather, a 26-year-old Apache/Yaqui activist, ascended the stage. Dressed in buckskin, she raised a hand to decline the statuette, stating Brando’s refusal was a protest against Hollywood’s “degradation” of Native Americans and the federal response to the Wounded Knee occupation, then ongoing in South Dakota.

The moment was electric. Boos mingled with cheers as Littlefeather, allotted just 60 seconds by producers, delivered a truncated version of Brando’s 15-page speech. He had written scathingly of the industry’s racist tropes, from “savage” stereotypes to broken treaties, linking them to the U.S. government’s violent clash with activists at Wounded Knee. The media exploded: Some called it a courageous stand; others dismissed it as grandstanding.

Behind the scenes, the Academy threatened to arrest Littlefeather, while John Wayne reportedly had to be restrained backstage from storming the podium. Brando, already a two-time Oscar winner, faced backlash but stood firm, later telling Dick Cavett: “The motion picture industry is responsible for creating a totally false image of the Native American.”

Though his protest spurred no immediate policy changes, it forced Hollywood to confront its complicity in systemic racism. Decades later, the Academy formally apologized to Littlefeather in 2022, acknowledging her “abusive treatment.” Brando’s act remains a defining clash of art and activism—a glittering night forever shadowed by the fight for justice.

8. The Only Oscar-Winning X-Rated Film

Midnight Cowboy (1969) remains the only X-rated film to win Best Picture at the Oscars. Directed by John Schlesinger, the gritty drama—starring Jon Voight as a naive Texan hustler and Dustin Hoffman as a tubercular con man in New York—confronted themes of poverty, sexuality, and alienation, shocking audiences with its unflinching realism. Upon release, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) slapped it with an X rating (then a non-trademarked classification for audiences 17+), citing “homosexual frame of reference” and “possible excessive violence.”

The X rating, initially intended for films with mature but non-pornographic content, had not yet become synonymous with explicit adult cinema. United Artists, the studio behind Midnight Cowboy, refused to cut scenes to appease censors, gambling on the film’s artistic merit. The gamble paid off: it triumphed at the 1970 Oscars, winning Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay. Yet the victory was bittersweet. Many theaters, wary of the X label, refused to screen it, and some critics dismissed it as “sordid.”

In 1971, as the X rating became increasingly associated with pornography, the MPAA re-evaluated Midnight Cowboy without requiring edits and downgraded it to an R rating—a rare reversal. Decades later, the film’s legacy endures as a cultural paradox: a harrowing portrait of American disillusionment that broke taboos, won Hollywood’s top prize, and forced the industry to reckon with its own boundaries. Its X-rated Oscar crown remains a defiant relic of a time when art dared to unsettle.

9. Oscar Statuettes Were Once Made of Plaster

As World War II rationing gripped the United States, even Hollywood’s golden idol bowed to the home front’s sacrifices. In 1942, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—facing critical metal shortages—abandoned its traditional 13.5-inch statuettes of gold-plated britannium (a bronze alloy). For three years, Oscars were instead crafted from painted plaster, a humble material that clashed starkly with Tinseltown’s shimmering self-image.

The switch began with the 15th Academy Awards in 1943, held at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub under wartime blackout restrictions. Winners like Best Actress Greer Garson (Mrs. Miniver) and Best Actor James Cagney (Yankee Doodle Dandy) received plaster trophies, their faux-gold finish a quiet nod to national frugality. The Academy assured recipients they could trade their “wartime Oscars” for metal versions post-conflict—a promise fulfilled in 1945, though some winners, like Casablanca screenwriter Julius Epstein, kept their plaster originals as historical oddities.

These provisional Oscars symbolized Hollywood’s uneasy dual role during the war: a purveyor of escapist fantasies and a participant in national austerity. Studios donated scrap metal for munitions, while stars like Clark Gable enlisted in combat. Yet the ersatz trophies also sparked quiet controversy. Some nominees grumbled about the diminished prestige, while critics argued the gesture was performative—after all, the ceremonies still unfolded with champagne and gowns.

Today, surviving plaster Oscars are coveted rarities. In 2015, one sold at auction for $79,200, its value inflated by the story it embodied: a fleeting era when even Hollywood’s highest honor became an unlikely soldier in the fight for victory.

10. The Oscars Were Once Almost Canceled

On April 4, 1968, America reeled as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, plunging the nation into grief and sparking widespread civil unrest. Just four days later, Hollywood’s glitziest night—the 40th Academy Awards—was set to unfold at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Faced with a fractured country, the Academy made a historic choice: postponing the ceremony by two days to April 10, marking the first time the Oscars were rescheduled out of respect for national mourning.

The decision was fraught with tension. Some studios and stars argued the show should proceed as a distraction; others, like Sidney Poitier, quietly withdrew, opting to honor King’s legacy off-camera. Host Bob Hope struck a somber tone, opening the delayed ceremony with a tribute to the civil rights leader. The night’s winners echoed the era’s turmoil: In the Heat of the Night, a thriller tackling racism, won Best Picture, while Rod Steiger dedicated his Best Actor award to “racial understanding.”

Yet the delay drew criticism. Many viewed it as a performative gesture, noting Hollywood’s own struggles with systemic inequality. The Academy, dominated by white male voters, had only honored one Black performer in a competitive acting category by 1968 (Poitier in 1964). Meanwhile, cities burned, and activists demanded tangible change, not symbolic pauses.

The 1968 Oscars remain a paradoxical footnote: a brief pause in Hollywood’s calendar that mirrored a nation’s anguish but underscored the industry’s uneasy relationship with the social revolutions it often dramatized.