Although great novels do not always translate perfectly to the screen, using a profound piece of literature as inspiration is rarely a mistake. Many of the hardest aspects of storytelling are crafting characters with interiority, developing a world that feels like it could exist beyond the confines of the specific narrative, and detailing a time and era that informs the context of the situation.

As a novel, “On Swift Horses” may have been pitched as an attempt to recapture the spirit of the “Great American Epic,” as there are innumerable comparisons to be made with the work of William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. As a film, Daniel Minhan’s directorial debut is absorbing and understated, even if it often feels overexerted in trying to bring to life every detail from the page.

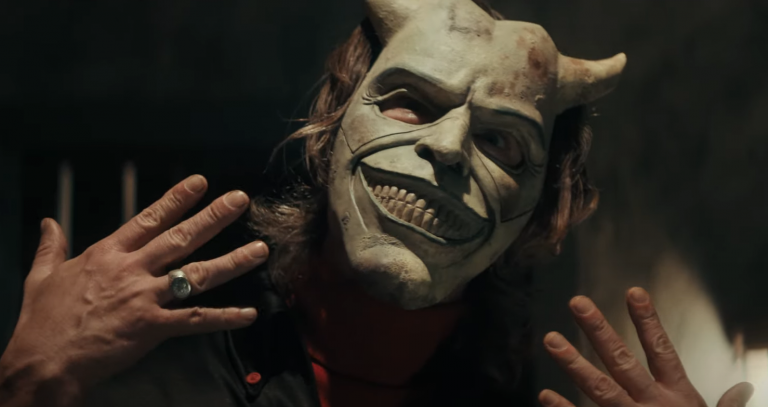

Set amid the Korean War, “On Swift Horses” explores the lives of the veteran Lee (Will Poulter) and his lover Muriel (Daisy Edgar-Jones), who agrees to marry him after a passionate plea to start a new life together. Although Lee believes that they have a future together in San Diego, the dynamics of his relationship with Muriel are subverted upon the return of his brother, Julius (Jacob Elordi), a charismatic card shark who wants to travel to Las Vegas.

Although they end up going their separate ways, Muriel and Julius share a brief moment of intimacy that offers them an escape from the societal boundaries that hold them back. However, their respective journeys to find new homes led them both to ask fundamental questions about their identities.

“On Swift Horses” is novelistic in every sense of the word. Between recurring symbols that speak to the characters’ societal status, the breathtaking visuals of the American landscape, and the divergent story structure, the film is dead set on reaching a poignant conclusion, which at times is a fault.

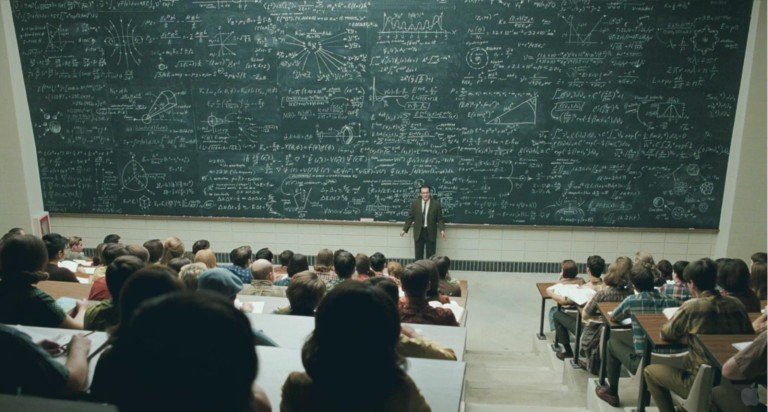

Minhan certainly knows how to capture the specificity of transcendent, seemingly insignificant moments in his characters’ lives, as his resume includes some of the strongest episodes of “Deadwood,” “Game of Thrones,” “Six Feet Under,” and “Homeland.” Individual scenes in “On Swift Horses” are often engaging, as they indulge in the rich historical detail inherent to a pivotal moment of social change within American history. However, it often does feel like a series of moments in search of an overarching theme; the latent connective tissue that appeared in the novel can’t be replicated within a visual medium.

The beauty of “On Swift Horses” is that the story is centered upon the revelation of emotional truth, not tangible goals, which allows the film to make use of an unorthodox structure. Julius’ adventures in Las Vegas may begin as a series of minor capers as he attempts to find steady work, but it evolves into a more gripping emotional affair with his coworker Henry, played in a very charismatic performance by “Babylon” breakout star Diego Calva.

Although “On Swift Horses” doesn’t dive into the failings of the American dream with as much venom as would be appropriate for the era in which it takes place, the brief passion and eventual fallout of Julius’ romance with Henry features the film’s most effectively existential moments.

Elordi is by far the film’s standout performance, as the role of Julius is not an easy one to define. Despite seemingly having the ability to charm his way into any situation, Julius is often at odds with himself and lacks clarity about what his long-term goals should be. While both Lee and Muriel have resigned themselves to the trappings of a marriage, Julius’ relative freedom puts him in a challenging position in which he must explore different opportunities with the hope that they may give his life meaning.

Despite the smirking facade that he often puts on, Julius is deeply terrified that he could disrupt the livelihoods of those with more direction than he does; the vulnerability that Elordi brings to the role is quite moving, particularly as Julius must mask the wholesomeness that is central to his personality.

In comparison, Edgar-Jones is given an equally challenging role, as Muriel’s slow exploration of sullied desires is ironically where the film feels safest. Despite the strength of Edgar-Jones’ chemistry with Sasha Calle, who appears as Muriel’s neighbor Sandra, the film rarely articulates what Muriel truly wants. This may be intentional, as some of the more interesting moments involve Muriel misinterpreting the dominance that each of her key relationships has within her heart.

However, these rare moments of complex intimacy are often surrounded by dramatic inertness. As good as Edgar-Jones is, her poise and manner are quite soft, as Muriel is only occasionally placed in a situation in which her emotions are heightened.

Poulter is the least served by the material, but gives a terrific encapsulation of what the idealized American entrepreneur looked like in the 1950s. While Lee is not without his rough edges, “On Swift Horses” makes the interesting choice to ensure that he is sympathetic, making the romantic triangle more fascinating to unpack. Although many other side characters slip in and out of the story, their purpose is mostly to challenge the status quo that Muriel and Julius find so impossible to maintain. Nonetheless, Kat Cunning is particularly memorable in the role of Gail, an illustrious woman who opens Muriel’s eyes to a lifestyle that she had never been exposed to.

While the scale of “On Swift Horses” is muted in order to highlight the grounded nature of the story, the production design, lighting, and costuming are as excellent as one would expect from a seasoned director of prestige television (which given the quality of Minhan’s previous work, is not a detriment). The pacing does significantly drag within the aftermath of a key encounter between Muriel and Julius, but it is to the film’s credit that it does not bend over backwards to appease convention. The most overt evidence of stylistic ingenuity is when Minhan opts for a more observational approach that isn’t afraid to devote significant time to tangential story beats.

“On Swift Horses” is a successful adaptation, an impressive debut, and a fitting showcase for a trio of the industry’s best young actors. Although the phrase “they don’t make them like this anymore” is often overused, it’s rarely better applied than to an unabashedly sweeping romantic epic about the weight of time. Despite the unevenness, “On Swift Horses” is a remarkably personal exploration of the lives of seemingly ordinary people, which in itself feels representative of critical historical moments.

![Lion [2016]: Contaminated Peace of a Lost Child](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Lion-768x513.jpg)

![Fury [2014] Review – A Brutal Tank Drama with Battle-Scarred Soldiers](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/fury-movie-wide.jpg)