My first brush with the anthropomorphic rendering of everyday objects was, in all probability, through the wildly popular children’s TV show “Blue’s Clues.” In “Blue’s Clues,” the host, the only human character, invites his audience to an eccentric world where everyday objects like a mailbox, a soap, a clock, and a line of pepper and salt shakers sing, talk, feel, and even reproduce! Subversion and unpredictability are particular features of this imaginative world created solely for children.

Rohin Raveendran Nair’s MAMI Select: Filmed on iPhone short film, “Kovarty,” shares little of the mentioned American show’s cultural circumstances and bears little similarity with its distinctive intellectual energy. However, it is not surprising that the short film tugs on the memory of the show, for both of them locate the grand gestures of life in the modest, ubiquitous materials. What sets “Kovarty” apart is Nair’s finely tuned creative tact in deploying and using the point of view of its protagonist, a typewriter. However, upon scratching the surface of the previous analogy, I find for “Kovarty” a better companion.

It is also undeniable how “Kovarty” consistently echoes the insistent ideological propensity of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s work. In his play, “Mystery-Bouffe,” machines are endowed with life: they are the actors of the Promised Land, “the Communist paradise of material plenty on earth.” Mayakovsky recognizes the true kinship amongst the proletariat and the machines and their intrinsic ties to the question of revolution.

In the preface to his socialist play, he writes, “In the future, all persons performing, presenting, reading or publishing Mystery-Bouffe should change the content, making it contemporary, immediate, up-to-the-minute.” Nair’s half an hour long “Kovarty” unknowingly and partially lives up to the testament of the poet.

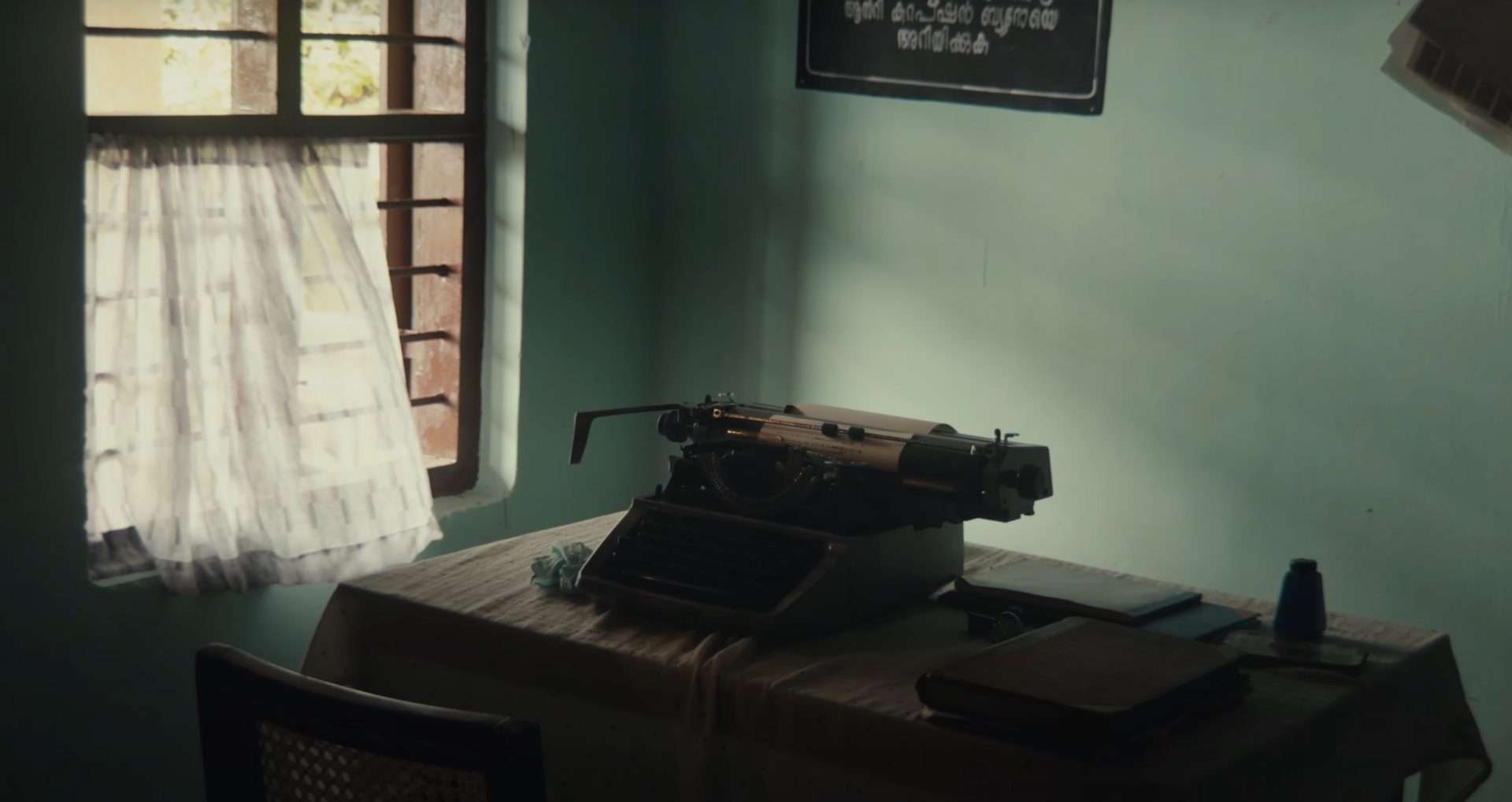

Set in Kerala of the 1980s, “Kovarty” opens with the ceremonial welcoming of a typewriter to the village of Thozhuthilmukku. The typewriter is an asset of the office of the sub-registrar. Upon its arrival, the new office typist, Daisy, holds it in her arms and places it in her office. The object instantly falls in love with her. Daisy insists that the church priest name the typewriter QWERTY. The arrival of the typewriter stirs up revolutionary changes in the unassuming village. It is entrusted with legalising the first interfaith marriage of the village.

The villagers recognise the typewriter to be the usherer of many such revolutions. The typewriter, meanwhile, harbours feelings for Daisy and steals the magnolias that adorn her hair. There is only one other entity aware of the growing feelings of this secret admirer: the office pendulum clock. Things move smoothly for a while, but as is the case with technology, the lives of both the objects stand threatened by the pending replacement with their far advanced successor.

Despite being referred to with masculine pronouns, the typewriter’s insistent viewpoint is neither masculine nor feminine. It seems to be a force falling outside the normative gender binary. Nair skillfully masters the gaze of the machine, endowing it with a vintage black and white colour tone. To achieve the gaze, he puts the iPhone inside the typewriter, something which is only possible given the compact size of the device. What Nair presents to us is the gaze of revolution itself through the object, and what we have at hand is the love story between a woman worker and her eventual political conscientization.

At a point in the film, Daisy takes the debilitated typewriter out for a stroll. The film pauses for a meditative observation, interrelating and interfusing Daisy’s conversation with the typewriter with shots of the backwater and scenery around it. Daisy pronounces her ‘Kovarty’ typewriter as different from the other machines, particularly the landlord’s car, which has graced the village.

Daisy tells the typewriter that the village landlord’s automobile has been beneficial only to him. This insertion instantly calls to mind the Uruguayan author, Eduardo Galeano’s angry tirade against the unfeeling might of automobiles in his “Upside Down: A Primer for the Looking-Glass World.” In his pithy essay, Galeano observed, “Cars are like gods. Born to serve people as good-luck charms against fear and solitude, they end up making people serve them.”

Similarly, Daisy describes the automobile as the first marvel of the village, but drops it from its inflated stature eventually, citing it as an exclusive preserve of an educated and privileged elite. The typewriter, diametrically opposite to the car, is dear to Daisy as it has consistently worked towards emancipating the lower classes socially, politically, and intellectually. As Daisy caresses the typewriter and utters these words, Nair presents us with a shot where the ribbon spools and the typebar are placed in such alignment inside the broken typewriter that it seems it is wearing a smug smile.

What “Kovarty” brings to the fore is also the identity-moulding relationship between a worker and their tools. Daisy’s conversations with Qwerty strike a sympathetic chord with both the boatman and the audience.

![Relaxer [2019] Review: Survival of the Unfittest](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/relaxer-768x461.jpg)

![This Is Not a Comedy [2022] Netflix Review: A resonating dark comedy dipped in melancholy](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/This-Is-Not-a-Comedy-768x432.jpg)

![Kaul (A Calling) [2016]: A Visually Stunning, Thrilling Existential Odyssey](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/kaul2-768x432.jpg)

![The Thief of Bagdad [1924] Review – A Wildly Entertaining Silent-Era Spectacle](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The-Thief-of-Bagdad-1924-768x432.jpg)