Tobias Lindholm’s third feature is an anatomical exploration of war, both on the battlefield and within the psyche of a Danish commander, Claus Michael Pedersen (Pilou Asbæk). It essentially is titled “A War” (Krigen, 2015) not ‘The War’ or simply ‘War’ – because the film seeks to locate the generic rationales of war in a specific episode – an act that rejects the standardized popular nomenclature of naming films, although not something new for Lindholm because for similar reasons he named his sophomore film “A Hijacking.”

Before joining the U.S.-led coalition to restore peace in the Taliban-afflicted Afghanistan, Denmark’s military exercises were extremely reticent. When, in 2001, they deployed their troops in Afghan provinces, accompanied by nationalist support from the Danish populace, the leaders of the nation couldn’t foresee the decision’s obvious, imminent impact on the psyche of their troops, who traditionally had remained restrained from engaging in combat. Upon their homecoming, the soldiers were found heavily dosed with post-war trauma. Yet this alone wasn’t enough; some of them faced court trials for inadvertently violating the military criminal codes.

The aftermath of the Danish state’s decision curbed their earlier popular support; even a handful of decision-makers began retracting from the very principles they once laid before the countrymen. Lindholm recollected this cloud of ambiguity that suffused the Danish hearts and minds at that time, “It’s not to protect our borders or to save our own families, but we asked young people to fly over to the other side of the world, to do what? Build democracy? Win hearts and minds? A lot of the soldiers I spoke to really didn’t know. Yet all of them told me that after 10 years of tours of duty, they had all changed immeasurably as human beings.”

“A War” is divided into two major episodes, coalesced with three interwoven narratives. While the first half crosscuts between the Danish army stationed in the Helmand province of Afghanistan and Commander Claus Pedersen’s wife, Maria (Tuva Novotny), who is struggling with their three children in Denmark, the second half unfolds mostly in a courtroom. The film begins with a long shot at dawn, depicting a routine army patrol in a desolate landscape. Anders (Alex Høgh Andersen), a soldier, swaps positions with a neophyte, Lasse (Dulfi Al-Jabouri), and mistakenly steps on an IED (Improvised Explosive Device).

These lethal traps, planted by the Talibans, were scattered almost everywhere near the army camps. Witnessing Anders lose a leg in the explosion, Lasse could no longer hold his emotional stability. His rapid breakdown makes him beseech Pedersen to send him back home. But Pedersen, unlike the regular war movie commanders, convinces him to stay with them and assigns him duties within the camp for the next couple of weeks.

Over the first sixty-odd minutes, the film follows Claus Pedersen and films his interactions, both personal and professional. The narrative, aided by a hand-held documentary-like camera, invites you to delve deep into Claus’s character, or I might argue, it asks you to understand how a commander actually operates beyond the fantasy world of cinema.

I’m arguing this on the basis of Tobias Lindholm’s obsession with creating actuality in his films. His compulsion to re-create real events with an edgy authenticity led him to use a real-life negotiator and Somali natives in “A Hijacking.” Pilou Asbæk and Søren Malling were left without a script in that film, so that they could anticipate the situation and act accordingly.

Anecdotes about the making of “A War” prove only the intensity of this growing obsession of Lindholm. Except for a few actors, he mostly cast veteran military personnel and former Taliban militants. This time, too, the actors again weren’t given a complete script, and since Lindholm shot multiple endings, the actors remained uncertain about their characters’ fates throughout the shoot. Claus is seen in several scenes interacting with local Afghans with the help of a translator. Lindholm later revealed in an interview that to achieve the authenticity of these scenes, Pilou was not provided with written dialogues, and he improvised his dialogues by anticipation and intuition.

The degree of authenticity Lindholm achieved in “A War” compels me to discuss a scene in which a sniper eliminates a militant. Here we see in a grainy imagery through the POV of a sniper scope, the militant excavating an explosive and then fleeing with a boy. He uses the child as a shield to escape the camouflaged snipers. After fleeing a certain distance, he drops the child, and therewith two sniper shots eliminate him. Lindholm filmed this sequence with praiseworthy diligence, and the scene can be regarded as an example of recreation of actual events in cinema, par excellence.

Culmination of these minute nuances has fulfilled Lindholm’s ambition of rejecting the obvious blood-thirsty shroud that often cloaks conventional war-cinema. Additionally, the film doesn’t shy away from class politics either. The conversation between Claus and the patron of a local Afghan family, who came seeking refuge in the army camp, is a rare example in the history of war-cinema that highlights the class supremacy of army personnel.

In exchange for pursuing a highly risky job of protecting a state’s border, soldiers often enjoy the luxury of a bourgeois lifestyle from the state. The poor Afghan straightforwardly unveils this fact when Claus tries to calm him down by pretending to understand his situation, saying that he himself is a father of three children. The native replies, ‘But they live in safety, though.’

Pederson, abiding by the military codes, refused to give shelter to the Afghan family, but breaching that same code, albeit inadvertently, led him to face an unforeseen trial. During a patrol, when Claus and co. finds out the local Afghan family dead in their house, they fell prey to an ambush. To save Lasse, who had been hit by a bullet, Clause asked for air support without having a PID (Positive Identification) and unintentionally caused civilian casualties.

(In Denmark, an error of this kind could cost a maximum of four years’ sentence, if proven guilty in court.)

Suspecting a possible casualty, Pedersen is sent back home. His surprise homecoming makes his wife put on a fake smile. After spending a brief time with the family, Claus and Maria go to consult their lawyer (Søren Malling), who advises Claus to claim in court that he had a PID during the clash. Another war, from here onwards, begins.

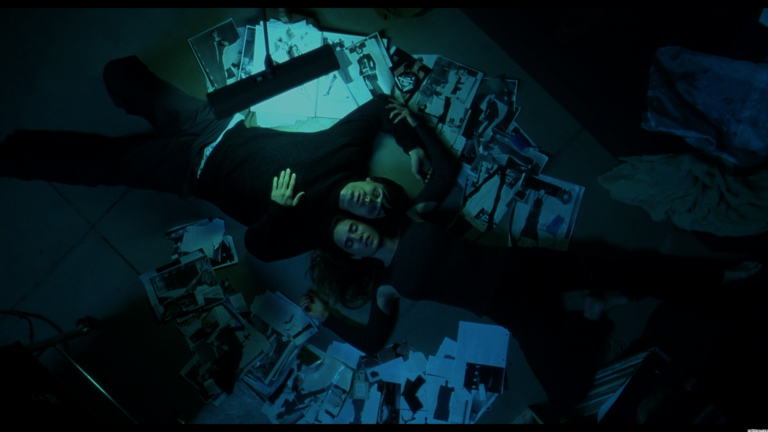

Claus’s struggle with himself is nothing less than a war. This inner war is poignantly portrayed in a scene where he confesses to Maria, his wife, that he must accept the punishment because he indeed is guilty of causing the casualties of eight children’s lives, and his wife retorts, “But you have three living ones at home.” His dilemma doesn’t end there. His restlessness, smoking cigarettes, and staring vaguely at the sky had been filmed evocatively in the subsequent sequence by Magnus Nordenhof (D.O.P.), who has done a remarkable job throughout the film.

The final episode takes place in a courtroom. Crossfire of arguments between two excellent actors, Søren Malling and Charlotte Munck, inquisitively unveils the fact that preserving the sanctity of ethics by abiding by the modern law and order sometimes might demand you to be cruel. Pedersen nevertheless receives an acquittal. A surprising witness statement by one of his fellows, ‘Butcher’ (Christian Krølle), paves the way for his acquittal.

Once the jury declares their decision, a sharp metallic score by Sune Rose Wagner blurs the dialogues around and amid the indistinct conversations, Claus sits down with teary eyes. These stirring final Mise-en-scènes in the courtroom set a new standard in the discourse of war-cinema.

Lindholm’s efforts to re-create real events have, arguably, redefined one of the most popular genres among all genres. His anatomical exploration of war, both inside and outside of one’s mind, wouldn’t have appealed to us this much if popular tropes had been employed in the film. What still appeals or perhaps haunts me most is the ending. Pederson, sitting on the patio, smokes alone and seems lost. A vague score permeates the screen, and the curtain falls. Will the war with his conscience last till his last breath?