True to the country’s colonial history, the British movie industry has always had its fingers in filmic pies across just about every corner of the globe, making it rather difficult to define what would even be considered a “British film” these days. We all, of course, have a baseline assumption for what we’d consider to be Britishness on the screen—Shakespeare and Jane Austen adaptations, Mike Leigh masterpieces, instant classics bearing the stamp of “Wallace and Gromit”—but the true reach of the UK’s grasp on cinema as a whole is very nearly as ubiquitous as that of the most famous colony to break away from taxation without representation.

In looking upon the best British movies of 2025, this more cosmopolitan presence is felt in the varied spaces that found a home for those pounds to be invested, and though many of the following films would be just as easily—if not occasionally more so—classifiable as the efforts of a coproducing country, the impact of that royal seal is felt nonetheless, even if in a less-than-flattering light shone upon the realities of such rampant imperialism.

Many of the following films reflect this dark reality, some don’t, and others find a wave all their own on their quest for the perfect afternoon tea. So before we say “Cheerio!” to 2025, here are the most notable offerings the United Kingdom gave us throughout the year.

10. Anemone

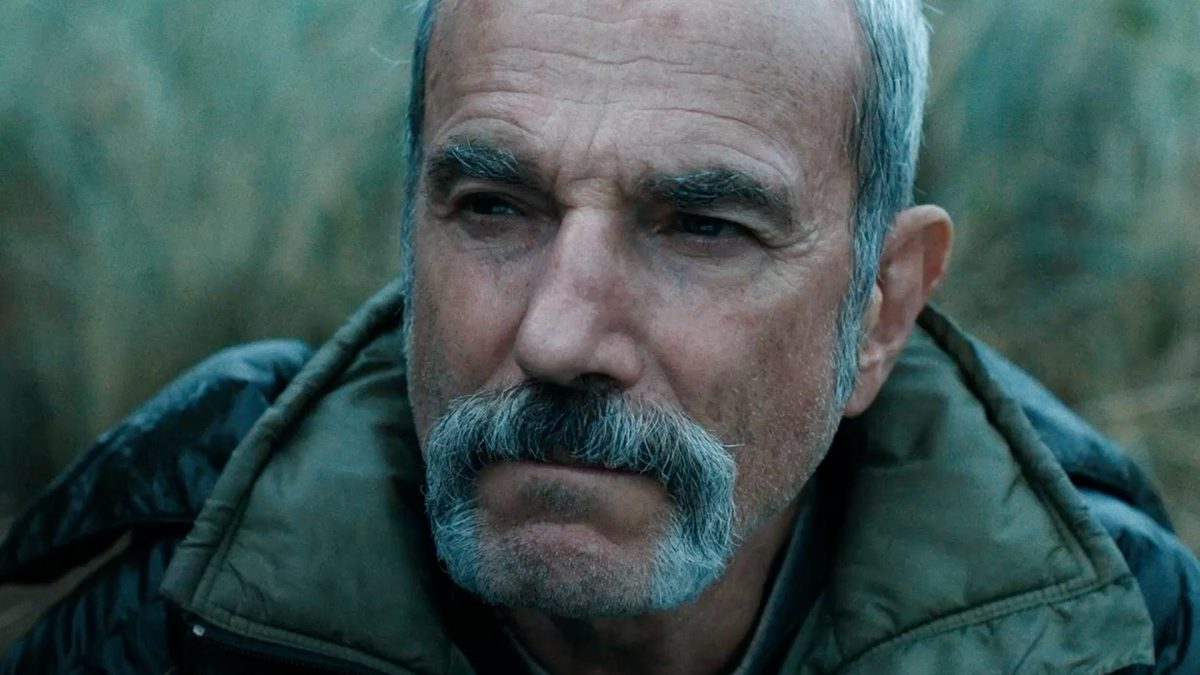

“Anemone” is a mess. Not even the film’s most ardent defenders will deny that Ronan Day-Lewis’s directorial debut is something of a muddled expression of its chosen thematic framework, relaying the traumas of wartime service to Northern Ireland with all the grace and cohesion of a meat tenderizer.

With that being said, any film that coaxes reigning Best Actor Alive Daniel Day-Lewis out of retirement—even if only as a favor to his own offspring—is doing something right, and “Anemone” gets further points for how it comes to inspire the veteran actor to find new ways to push himself without ever losing track of what makes his chosen vessel one whose struggle might just be worth enduring.

As Day-Lewis Sr. and Jr. collaborate in the scripting stages to find a malleable view of parenthood and responsibility, it’s undeniable that “Anemone” exists as something of a joint therapeutic exercise for the newly minted creative duo. As such, the film’s lethargy almost becomes part of its charm, as Ronan refuses to play it safe even with the guaranteed exposure his father’s presence offers the project. Even if the collaborative synergy on display clearly needs further nurturing, “Anemone” hints that its own existence may be a necessary step towards that prospective unity both on and off the screen.

9. The History of Sound

As handsomely assembled as its two leading men—even if in service of a tame vision of unexpected and unconventional love in an age of war—Oliver Hermanus’s “The History of Sound” almost needs nothing more than its elevator pitch of “Paul Mescal and Josh O’Connor play folk music recordists who get freaky amid the backdrop of the First World War” to at least drum up a modicum of audience intrigue. In a way, the film seems almost more interested in its titular quest to catalogue and immortalize the sorrows and triumphs etched into the music of America’s rural pastures than it is in the sweaty romance between its two it-boys.

This becomes both a vice and a virtue for a vision that never fully surpasses the standardized Oscar-bait promised by its premise. Still, if nothing else, there remains a sincerity to the director’s crisply realized perspective on the tenderness of a gay relationship whose screentime is far less than that given to the aches that grow in their time spent apart. Uneven as this focus proves, Hermanus brings his typical sympathetic touch to a textured view of a time and place nearly lost to the history of the world, made all the more distressing by its relative recency.

Check Out: Top 10 Worst Best Picture Nominees of the 21st Century

8. Paddington in Peru

The only film on this list to outright name-drop an entirely different country in its title may very well remain the most British film here, thanks in no small part to its central marmalade-enamored presence. “Paddington in Peru” may not match the heights of Paul King’s preceding duology—few films of any sort can—but Dougal Wilson’s admirable attempt to bring the beloved bear to his roots makes for an expectedly wholesome expedition towards the jungles of his birth.

With some familiar faces and a few new ones in the mix—Antonio Banderas and Olivia Colman are always cheat codes. But, Emily Mortimer replacing Sally Hawkins, sadly, not as much. Wilson’s take on Paddington retains much of the series’s warmth with little Amazonian humidity.

Ben Whishaw, naturally, proves the most essential element in keeping “Paddington in Peru” grounded in its most soothing orange orchards, as the most politely British-sounding voice since Colin Firth (we still can’t imagine what this character would have been like with him as the original casting choice) guides us through the treachery of a setting whose greatest threat—as it turns out—is the greed of man. The most original message in the world? Not really, but sometimes, it’s less about what exactly you’re saying than how poshly you can say it, and Paddington Bear always has that teatime delivery locked in and ready to go.

7. 28 Years Later

For those of you less inclined towards a rosy view of the British Empire—for those of you who see the birthplace of rampant colonial expansionism as a hotbed of soulless zombification in desperate need of rediscovering the humanity that should theoretically course through its deadened veins—Danny Boyle sure has the film for you!

Of course, “28 Years Later” isn’t the first time Boyle has reenvisioned the Island of Great Britain as an isolated petri dish of raging violence that finds equal danger between the superspreaders of the apocalypse and those last vestiges of humanity left to survive it, but his return to the series that made him a household name proves far more considered than most long-dormant franchises resurrected from the grave.

Once again experimenting with (relatively) low-tech camerawork to give his version of zombified Britain a more personally kinetic feel, Boyle never lets his playful grasp of form fully overtake the human stakes that are intended to drive us through the overgrowth. Ralph Fiennes, Jodie Comer, and newcomer Alfie Williams ground “28 Years Later” in a vision of hell that reminds us that even in a deteriorated landscape so far gone, there remain a few seedlings of human compassion that can grow firmly with just a few moments in the sunshine.

Interesting Read: How ’28 Days Later’ Revitalized The Zombie Film

6. Grand Theft Hamlet

As I said in our introduction, you can hardly get more English than Shakespeare. So prevalent is the influence of the Bard, in fact, that the impact of his words can even be felt in the cyberspace of a digitized Los Angeles designed expressly for the purposes of violent carjackings! Sam Crane and Pinny Grylls, with “Grand Theft Hamlet,” explore the communal healing power of theatre in an unconventional venue when the isolating horrors of the COVID-19 pandemic left many an artist struggling to find any real meaning in their work at a time when the world as a whole seemed at a complete standstill.

Bringing together both the poignancy of Shakespeare’s writing and the unsuspecting power of unity in a space that unites equally despondent souls from all across the globe, Crane and Grylls harness the triumphs and tribulations of such an undertaking to show where the drive even to tackle such a seemingly innocuous and foolhardy endeavor is a testament to the fortitude of the artistic spirit. Somewhere between “To be or not to be” and “Fuck you, and your mama too!” lies the distinct artistic space that “Grand Theft Hamlet” exists to celebrate.

5. Pillion

It’s a razor-thin tightrope for a film to walk—in particular, a film outside the explicit educational framework of a documentary—when it promises to depict a sexual kink with the sort of blunt honesty that dignifies its value at the same time that it acknowledges its potential faults. Even more daunting is the prospect of such a film being its director’s introduction to the world, but Harry Lighton’s forthcoming and empathetic “Pillion” manages to come out of the gate swinging with a gorgeously tender and disarmingly funny examination of BDSM relationships and the difficulties that come with meeting a lover on the terms of their preferred modes of pleasure.

With the help of a dynamically timid Harry Melling and a hulking but layered Alexander Skarsgård bringing tumultuous life to this anxious association of domination and submission, “Pillion” retains a consistent sense of care for what this relationship can represent outside of deliberate shock value, treating every one of its proposed modes of sexual gratification with a sense of respect entirely contingent on the mutual understanding of its participants. We all want to support each other’s unorthodox modes of expressing passion, but Lighton shows how that acceptance will always have its limits; it’s just human nature.

While You’re Here: The 20 Best BDSM Movies Of All Time

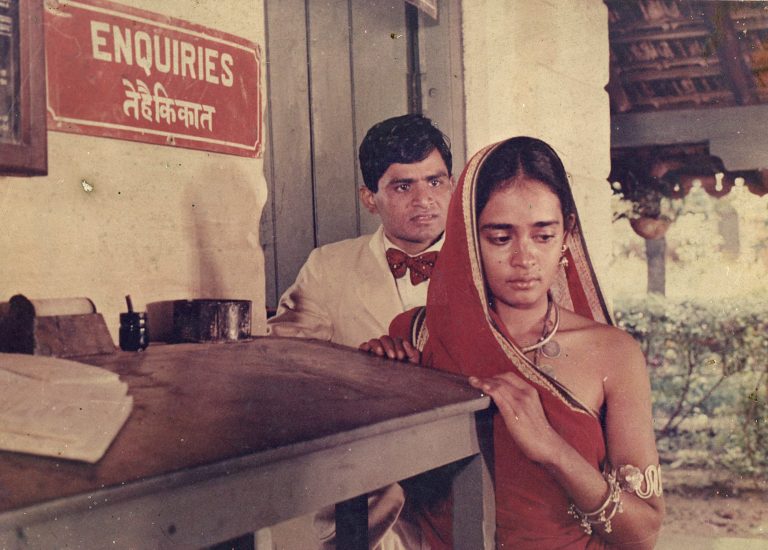

4. My Father’s Shadow

And what is one of our annual national ranking lists without just the slightest whiff of cheating? Some may argue that Akinola Davies, Jr.’s nostalgically elegiac debut “My Father’s Shadow” is too blatantly a Nigerian film to be considered British. While the UK’s Oscar submission committee would disagree, the argument is as obvious as it is valid.

That being said, even without considering the major British funding applied to bring life to Davies’s requiem of a childhood that felt like a distant ghostly vision, it can surely be argued that the film and its depicted political moment could not exist without its own lingering shadow in the form of British colonial interventionism, laying the groundwork for a corrupt political dominion that gained power at a moment that finally promised a break from the recent horrors of settler expansion.

“My Father’s Shadow” always has that spectre of change—or rather, the sobering reality of a lack thereof—hanging in the background of what is otherwise an ode to the parent whose overwhelming absence never diminished the obvious care and sacrifice for his children that came with such long bouts of reluctant disappearance. Davies thus takes us on a fragile familial odyssey through Lagos, viewing the Nigerian city as a whole world in itself, rife with opportunity and disappointment as the reality of any metropolis’s mechanizations slowly comes to the fore.

3. Hamnet

If that brief detour outside the borders of the UK felt a bit too divergent for you, then allow us to compensate with ANOTHER bout of Shakespeare! Now granted, “Hamnet” is also an American coproduction (I don’t think anyone will be labelling Chloé Zhao a homegrown Brit anytime soon), but the textured tale of old Bill’s most famous tragedy oozes with the atmospheric melancholy of the distant Stratford woods to ground the seismic fame of “Hamlet” within a moment of unspeakable personal catastrophe.

Jessie Buckley and Paul Mescal prove entirely capable and essential in relaying this sense of loss with the smallest quivers and the most sudden bursts of unexplained frenzy, ensuring that “Hamnet” never loses itself in the grand expression of grief and tumult that could so easily overtake any piece that takes its inspiration from the most celebrated dramatist in the history of literature.

Zhao’s intimate restraint at times gives way to sweeping floods of emotional overflow. Still, it always comes in service of a moment whose need for catharsis—and inability to truly find it—becomes the driving force for every one of its affectionately driven creative decisions. A soliloquy has rarely taken on such gutting connotations as when “To be or not to be” began to feel like an admission that there is nothing left to be at all.

Must Check Out: All 4 Chloé Zhao Movies (including “Hamnet”), Ranked

2. Urchin

In a year that saw more than a handful of celebrated actors taking their first spin behind the camera, British hunk Harris Dickinson proved by far the most capable with his deeply humanist character study “Urchin.” Frank Dillane leads this tale of homelessness in London with a headstrong wit that sucks us into a portrait of despair made just as tragic by its own subject’s obstinate attitude as it is by the obvious systemic hurdles placed before him as he makes the few noble attempts available to him to climb out of a perpetually self-digging hole.

With just a dash of the surreal to color the streets of his homage to kitchen sink realism, Dickinson’s debut remains a focused and expressive unpacking of a broken system. At the same time, Dillane’s sticky presence ensures that “Urchin” never loses the edge of its difficult protagonist in the sympathy it garners for those trapped within the cyclical prison of life on the fringes. There is, however, hope to be found in Dickinson’s startlingly compassionate vision—if not necessarily the hope of escape, then at least the hope of a personal battle whose failures may yet become a lesson learned in the quest for a moment’s peace somewhere down the line.

1. The Testament of Ann Lee

Exactly the sort of tectonic historical piece one would expect from the creative team behind “The Brutalist,” just one year later, Mona Fastvold’s “The Testament of Ann Lee” finds her and partner Brady Corbet looking to the strange allure of the Quaker movement to translate a religious experience to the screen in ways hitherto unimagined. Though not quite as thematically dense as some might hope, Fatsvold’s vision rings with a haunting instinctiveness that needs only to translate the magnitude of its search for meaning to justify the reality that such a search is always bound to come up empty-handed.

Amanda Seyfried’s career-defining performance brings Ann Lee’s little-discussed legend with a soft, trembling touch, poisoned by the urgency of a delusional belief in having the key to life’s mysteries. As such, “The Testament of Ann Lee” resonates like a fabled tragedy, rooted in the history of humankind despite its relative obscurity.

From one end of the Atlantic Ocean to the other, Fastvold’s tale of religious enlightenment never shakes the poisonous reality that affects all stories of colonial conquest, as even the most innocently driven delusions of expansion are destined to leave all in their wake stumbling for a balance within themselves that can never be found by subjugated wills on subjugated lands.