Gabrielle Brady’s new film, “The Wolves Always Come at Night” (2024), follows a Mongolian couple uprooted due to the ongoing climate crisis. It presents their lives through a docudrama to help us understand their pathos better than impersonal observations. In the past, films have often shown ecological crises as a concern for a distant future. Whether intentional or not, those projects left us with some form of hope for a safer future than what appeared on screen through a change in personal or social behavior. Sadly, they didn’t help turn the wheels in ways that mattered most, leaving us experiencing catastrophes around the globe.

The worst part is how it affects people who are not contributing to ecological damage, which includes the protagonists of Brady’s film. They lead their lives away from industrialised society and follow their traditional ways of being. So, almost everything in their lives is geared toward them being self-sufficient.

They take great care of goats and horses, which in turn help them with milk or transportation. So, they don’t need external forces to help with their livelihood. Furthermore, they live in a sort of house that can maintain its original shape even if it collapses and needs to be rebuilt. However, their mode of life has become increasingly difficult to sustain in the presence of unpredictable winds and storms.

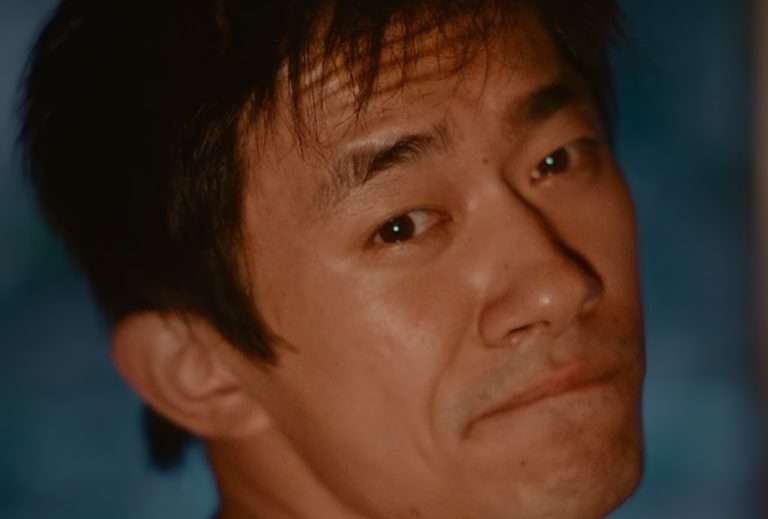

Before exploring the aftermath of a similar crisis, Brady offers an intimate look into their daily lives, highlighting beauty in its dizzying monotony. She opens her film by showing the father riding a horse through a wide and empty desert, but the emptiness doesn’t feel gloomy or unforgiving like our fictionalized notions about such spaces. Instead, it feels quietly tender and inviting, and every image you see may seem innately gorgeous. That’s likely why the entire film paints this setting with a dreamlike, glistening softness. The credit goes to Michael Latham’s lensing choices, among other creative inputs, which make its beauty impossible to ignore or resist.

Watch The Trailer:

Brady uses visual beauty to keep us hooked to the comforting pace of their lives, lulling us through the seemingly inconsequential details of their routine. She shows the father looking at a herd of goats in a desert through binoculars. After noticing a goat struggling with the weight of her unborn child, he rides her motorcycle all the way to her to alleviate her burden.

The camera reveals every single detail in this process, switching from wide-angle shots to intense close-ups, slowly tightening its emotional grip over us. Later on, the camera captures the innocence of kids as they tell stories in the presence of a dim torchlight, filled with mystery and horror specific to them. No matter what angle, everything feels deeply personal and moving.

Also Read: Who Owns Nature? ‘Jugnuma’ and the Politics of Ecological Memory

Brady emphasizes these emotional aspects to make the stakes feel immensely personal. She tries to bridge the gap between ‘them’ and ‘us’ by making our hearts break for this family that migrates from a quiet desert to a satellite town, not out of choice but for lack of it. Even here, their lives remain monotonous, filled with repetitive tasks.

However, unlike before, when they could at least be at peace with themselves, they are less in control of their lives than ever before. After migrating, the father ends up being another cog in the wheel of the country’s industrial growth, likely fuelled by their hitherto untapped mineral wealth. So, the harmony with nature is replaced with a morbid acquiescence.

Throughout her film, Brady’s focus remains on the personal to convey the universal anxieties related to climate change. She captures the heartwarming bond between family members, including the goats and horses they care for, through moments that we can seamlessly resonate with. Although naturalistic for the most part, it occasionally takes some magical realist detours to explore inexplicable details of their psyche.

Latham’s camera, along with Aaron Cupples’s score, becomes the film’s strongest suit, making the film a transportive experience. Katharina Fiedler’s editing helps further by maintaining the mystical, sentimental beauty in everyday moments, while leaving enough space to keep us mulling over the underlying subtext.

The film’s microscopic lens reveals the effects of the climate crisis through its lyrical storytelling. Yet, the same approach keeps it away from addressing the bigger factors in play behind the pathos. Its hypnotic beauty isn’t enough to offer a complete picture of what’s at stake. Ultimately, it leads our sympathies towards nothing more than sorrow for the unavoidable effects of climate change by tying its narrative with something poetic, but not constructive.

Nonetheless, it evokes a profound sense of loss for the world left behind, subtly juxtaposing the family’s past with the present, where the blinding warmth of the sun is replaced by barely perceptible, frustratingly impersonal nature of the streetlights, or an empty but inviting desert is replaced by a semi-urban space crammed with houses till the end of their vision, leaving them with little room to breathe. Unlike before, wolves have gotten closer than ever, and can’t be fended off anymore.

![I Am Vanessa Guillén [2022] Netflix Documentary Review: Horrifying true story of a 20-year-old soldier murdered in her Army Camp](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/I_Am_Vanessa_Guillen_Documentary-Review-768x669.png)