Cinema has gone through a drastic transformation in the past few years, which has affected its form and structure. Hence, there’s an increasing number of movies using a subtext-as-text approach to make things abundantly simpler for the audience, thus getting rid of the mystery that lies in the act of discovery. Trailers are also culprits in this case, revealing far more than the script’s introductory setup.

In theory, Tawfeek Barhom’s short film, “I’m Glad You’re Dead Now,” faces a similar challenge. The title reveals a crucial chunk of its story. It makes us anticipate someone dealing with their complicated emotions upon someone else’s death. Despite that limitation, Barhom manages to turn it into a revelatory piece of cinema, captivating us with its brooding mystery.

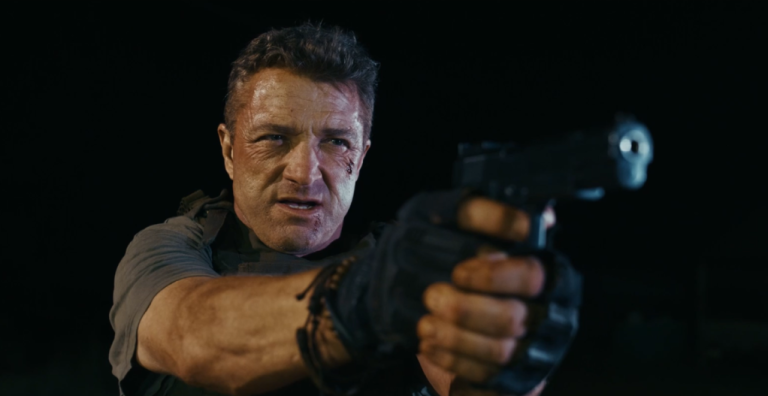

The film introduces its characters in a desolate setting with only a dim light or two to show what they are doing. It doesn’t reveal everything there is to know about these characters or their interpersonal relationship. Yet, it offers a sense of underlying sentiment that defines their bond. We see Reda (Tawfeek Barhom) working on something in the dark by himself in the presence of moonlight. He remains deeply absorbed in his work, but it doesn’t reveal everything there is to know about his emotional detachment from the world. His eyes look frighteningly empty in a way that you would describe a killer’s eyes or a traumatized victim’s.

Tawfeek’s script doesn’t clarify the reason behind that emptiness. Instead, it maintains that ambiguity even after inviting another character into the equation. We see Reda looking behind to find Abu Rashd (Ashraf Barhom), worried and confused. Abu Rashd asks him about his father with a childlike innocence that seems odd for a man his age. His eyes express a cautious mix of dread and concern, pushing us further down the rabbit hole of theories about these characters. Until then, we don’t know how they are related, nor do we know anything concrete about the relation between Abu Rashd’s query and Reda’s actions.

Also Read: A Trilogy of Grief: Cinema as Catharsis

As the film clues us in on more details about them, it compels us to reflect on themes of grief and childhood trauma. The film depicts the weight of residual emotions through a character’s absence, which reminded me of an essay from Rachel Cusk’s “Coventry.” There, she talks about an old couple cutting ties with their daughter by refusing to speak with her. Although a cowardly or childish gesture on their part, they consider their absence would serve as a form of punishment for their daughter, making their presence felt even more prominently than before.

In another essay, Cusk talks further about the complexities of parent-child relationships and the ways in which parents exert control over their children. When kids are young, parents can do so by physical means or by simply ordering children and expecting them to behave according to their wishes, which becomes impossible as they grow up. The pathos of Reda and Abu Rashd lies in a similar terrain, where pain was inflicted to exert control over them when they may not be capable of protecting or defending themselves.

The film gradually reveals details about that traumatizing pain through interactions between these two brothers, who struggle to forgo its emotional burden. Yet, Tawfeek refrains from using long-winding monologues to address their turmoil. He merely hints at the truth about their history, instead focusing on the emotional weight of their pain, presenting it through their body language and gestures. That’s why Abu Rushd and Reda both look like ghosts trapped in their oppressive past.

Also Check: The 10 Best French Movies of 2025

Tawfeek’s film feels like a cleansing act after a long stretch of unnerving nightmares. He makes us feel the numbness that the brothers were left to contend with for much of their lives. That isn’t a simple feat to achieve within a span of only 13 minutes, but he manages it through his economical use of creative tools.

He shows the characters in only two extended scenes, the second of which captures them largely in profile, from behind, with only the sound of waves in the backdrop of their gentle voices. Those choices allow the film to convey emotions without interruption, compelling us to sit with the discomforting details from their interaction, where characters are afraid to face their anxieties as they are to face us, while reflecting the echoes of their past through a seemingly endless ocean.

The performances heighten the tension further, especially Ashraf’s, whose eyes quietly convey the pains of remembering what ought to be forgotten or long buried. His crouched and reserved body language, along with a voice, gravely but somehow light as a whisper, takes us alarmingly close to Abu Rashd’s anguish, offering a palpable understanding of his dread.

Thanks to his dedicated performance, we can even feel the acridity of a lemon he bites into during that scene. He and Tawfeek make us feel like we’ve known these brothers for many years, as we hear them reveal the depths of their shame or embarrassment, seeking escape through soul-crushing rituals. The sheer pain they feel in those extended moments makes us realize just how liberating someone’s death must have been for them.

![Laali [2020]: ‘DIFF’ Short Film Review – A quirky tale about longing for love](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Laali-Short-Film-1-highonfilms-768x384.jpg)