Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rear Window” positions the viewer as a voyeur. Here, we’re mostly confined to Jeff’s (James Stewart) tunnel-visioned perspective, which allows us piece together the lives of those he’s observing. But “Rear Window” isn’t the only Hitchcock entry obsessed with the act of looking, or with the voyeur secretly ogling at something they shouldn’t.

In Hitchcock’s “The Pleasure Garden,” we see a man leering at Patsy (Virginia Valli) before her dance performance onstage, using binoculars to zoom in on her body without consent. But the moment he approaches her in hopes of fulfilling this misogynistic fantasy, Patsy laughs at him, rejecting the degrading male gaze that introduces us to her in the first place.

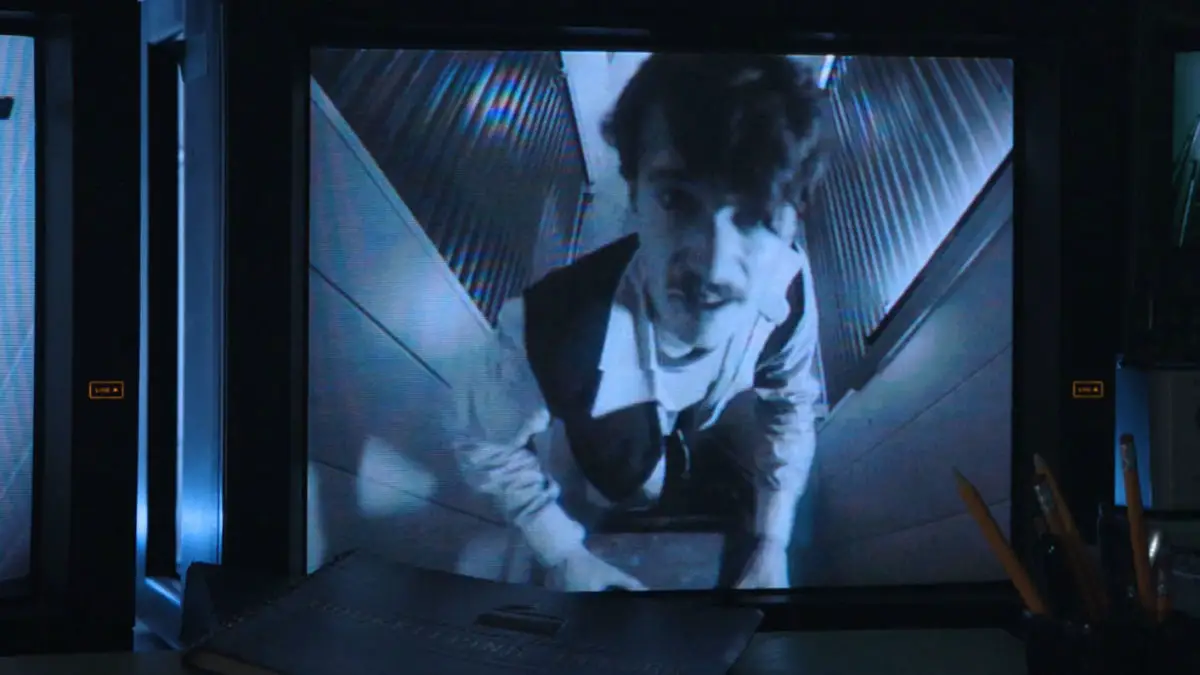

Writer/director Max Neace’s “Shift” leans into this Hitchcockian ethos, but the approach is more lighthearted than psychologically complex. This is a rather tricky tonal balance to pull off, especially considering the one-location premise that blends elements of “FNAF” with a tense, slow-burning mystery. Night security guard Tom (Connor McGill) starts his new job at a rental storage locker facility, hoping to “clear his head” in the meantime.

Owner Hal (Sean O’Bryan) lays out a list of basic rules, stating that the job should be fairly straightforward, considering its humdrum nature. At first, this seems true: Tom spends his days ordering takeout, writing sticky-note reminders, and changing the tapes to label them as instructed. But an increasing fascination with customer Scarlet Jones (Allison McAttee) sets Tom on a dark, wacky path, his eyes remaining glued to the screens, tracking her movements.

Scarlet, a married woman, brings a young man to her storage locker, but this man isn’t seen leaving on the cameras. Tom claims that he’s not fascinated by the salacious nature of the encounter, but by the mystery behind this seemingly missing person. Turns out, it’s a bit of both.

Neace leans into the absurd from the outset, introducing us to the armchair (!) on which Tom sits while carrying out his surveillance job. This chair, Grace, has her own set of values and personality traits, holding conversations with Tom (and Hal) through subtitles, even interjecting when required. This running gag is used to great effect, as the chair’s swivels are used to simulate the act of watching, where the perspective swings from one surveillance camera to the next.

In fact, almost every scene is conveyed through a voyeuristic medium: we watch Tom observing everyone who comes and goes, noticing how his gaze zooms in on Scarlet until he develops a morbid fascination with her. There’s also the anxiety of the watcher being watched, as privacy is a myth in this liminal space where every act is a performance for someone else to dissect.

Read More: 20 Best Movies of Alfred Hitchcock, Ranked

The problem with “Shift” lies in its superficial approach to these themes, where the humor used to offset serious drama ends up cheapening the suspense. There’s a genuine kernel of curiosity nurtured when we realize that something is amiss with the Joneses, and that their storage locker potentially holds disturbing secrets that are best left undiscovered.

But this speculative suspense is juicier than the climactic reveal, which feels rushed in the shoddy third act that doesn’t seem to know what to do with its characters. The pleasant humor that worked so far falls flat at this critical juncture, as we realize that the serious mystery thriller aspects are completely half-baked.

Scarlet’s framing as the femme fatale is also pretty one-dimensional, as this character is devoid of any nuance when we finally get to meet her in the flesh. Tom’s perception of Scarlet, which was once defined solely through the act of watching her do something illicit, transforms into full-blown fantasy fulfillment once they are face-to-face.

Even though Tom thinks he is in a position of supposed power as the voyeur, his picture of Scarlet is clouded and incomplete, as his perception of her is tinted by his own mommy issues and attraction to the femme fatale figure. These elements, though intriguing, aren’t explored with genuine intent at any point, as “Shift” is too busy with its convoluted central conceit and offbeat humor.

What makes “Shift” worthwhile, however, is its stellar usage of one location and its ability to create atmospheric tension that ramps up right until the unconvincing third act. Cogent use of perspective and tracking shots contributes to the sense of claustrophobia, along with the all-pervasive male gaze that Tom directs at Scarlet to solve the mystery. Performances, though scattered and uneven, are serviceable enough to suspend disbelief, but there’s the lingering sentiment that McGill’s character could’ve been much more fleshed out than it is.

“Shift” won’t scratch any itches pertaining to the themes of postmodern voyeurism and the way it shapes men’s perception of women, but it is an interesting examination of these dynamics through the lens of a mundane one-location mystery-thriller. If you like the idea of talking chairs and escalating slow-burns, then “Shift” might be worth your time.