“P77,” also known as “Penthouse 77,” is a Filipino psychological horror film directed by Derick Cabrido that resists the comforts of conventional genre thrills. Its horror unfolds patiently, favouring psychological unease over spectacle, which may unsettle viewers expecting constant shocks. Slow-burning dread is not an everyday indulgence, and Cabrido uses that restraint to probe themes of loss, pain, and guilt. Rather than relying on jump scares as punctuation, the film immerses the viewer through atmosphere, moral unease, and a carefully sustained ambiguity. Cabrido’s social commentary is sharp and discomforting, holding up a mirror to the audience, forcing moments of aversion, then drawing them back through the narrative unreliability of its central performance.

P77 (2025) Plot Summary & Movie Synopsis:

Luna, Jonas, and the Illusion of Escape

Luna (Barbie Forteza), a young woman from the slums of Manila, cleans murals and gravestones while looking after her asthmatic brother Jonas (Euwenn Mikaell). Her sense of responsibility for her brother borders on obsession. In many such tender moments between the siblings, her single-minded want is to move her brother out of the squalor of the slums into a high-rise where he won’t be bothered by dust.

When Luna’s mother, Natalia (Rosanna Roces), turns up, she comes with an opportunity for Luna to work on a cruise ship. The money would be significant for the Caceres family. Luna’s hesitation arises from her mother’s unreliability, coupled with the anxiety that Jonas would be left without anyone to care for him. She accepts the job and promises Jonas that she will constantly be in touch with him through calls, and leaves her mother and grandmother in charge of Jonas.

Her first few days at the cruise are filled with laughter and romance. She introduces Jonas to all the staff through FaceTime. Until one fine day, she receives a call from her brother who suddenly has an asthma attack. With both her grandmother and mother unavailable, he is seen collapsing in the video call. The camera becomes unreliable, and Luna becomes distant. She tries to kill herself by throwing herself off the cruise deck.

After being sent back home, she reunites with her brother, only to discover that her mother has disappeared. As she starts to search for her mother, she finds a leaflet in her mother’s box of a building known as P77. As she nears the building, a beggar stops her with a warning: people who enter rarely make it back out. She ignores him, pushing past both the warning and her own misgivings. The building’s unsettling architecture, combined with a building manager who claims to recognize her immediately, leaves her visibly shaken. He tells her they have been expecting her ever since her mother spoke of her, and that she is to begin work for the Cambions.

Luna Accepts the Cambions’ Offer Despite the Warning

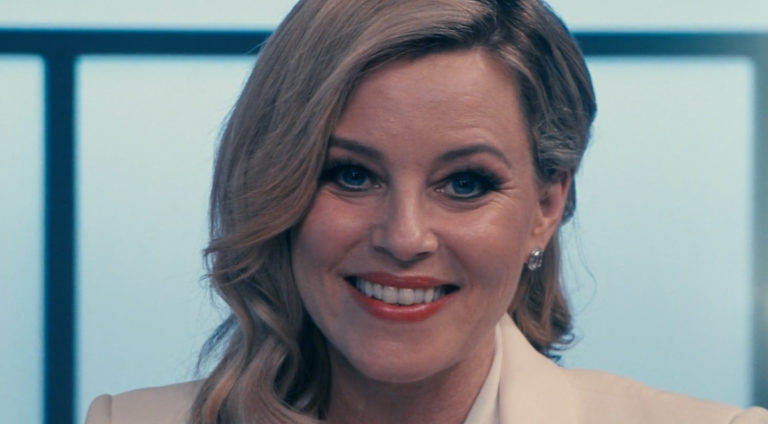

On the 77th-floor penthouse, Andrew (Carlos Siguion-Reyna) and Sonia Cambion (Jackie Lou Blanco) offer her a house-sitting job while they are away, even as they insist they have no memory of her mother. The contradiction unsettles her, but the need for money to support her brother outweighs her doubts, and she accepts the job.

After her episode on the cruise, she is put on benzodiazepine, which is a strong antidepressant, and she is faced with waking nightmares. She brushes them off, and as the Cambions depart, she decides to bring her brother with her to work. She begins to enjoy the privileges of house-sitting, indulging in one of Sonia’s dresses and using her bathtub to clean both herself and Jonas, though these moments of pleasure are disrupted by recurring nightmares in which she nearly drowns in the tub and is pursued by a supernatural presence. Suddenly, she is greeted by Sonia, who mentions her mother and how she was caught stealing. As Sonia leaves, Luna begins to experience eerie visions where Jonas also starts to turn on her.

Theo Reveals the Truth and Luna’s Reality Collapses

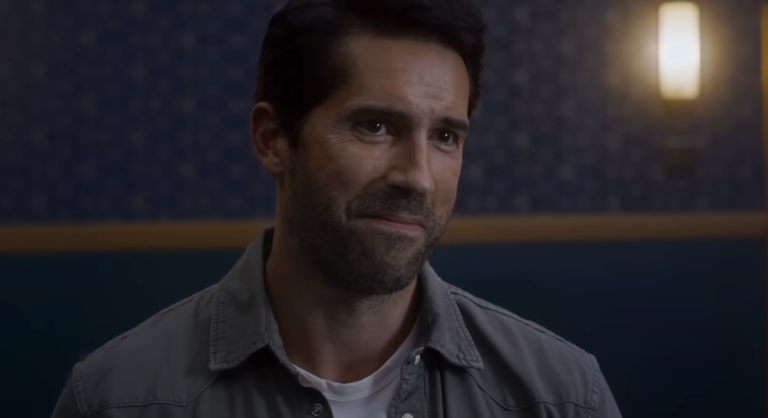

Luna is suddenly greeted by Theo (JC Alcantara) in the penthouse, who knows how the building came into being. She is informed that, before the building even existed, it was a hospital and the penthouse was a morgue. Then it became a sex dungeon before it was converted into this high-rise building. He rehearses with her for a masquerade ball and later extends an invitation. As the penthouse gradually transforms into a ballroom, she is confronted by an increasing number of unsettling figures, culminating in her encounter with the Cambions, who are revealed to be Theo’s parents. He asks her to stay in the penthouse, as no one ever leaves. Confronted by the spectral figures chasing her, she and Jonas try to escape, only for Jonas to get stuck.

The big twist begins to unfold at this exact moment. It is seen through a security camera that Luna is banging on a dilapidated gate and is confronted by the security guards. The guards show her a video of the last 48 hours, where she is inside, but no such building exists. It is merely a garden in which she is seen repeating her earlier actions and conversations, only this time in complete isolation. She flees home to find her mother and grandmother while the Cambions wait for her.

They reveal themselves as the owners of the cruise, explaining that the job offer was an attempt to reach her again after the emotional trauma she endured onboard. The building called P77, they clarify, never existed; it was merely a misreading of the cruise leaflet. A neighbour’s testimony—that she had always been alone—brings narrative clarity, exposing that her brother had died long ago and that she had buried the loss by constructing an alternate reality. Surrounded by quiet support, she finally confronts the truth, accepts its weight, and arrives at the closure she had long been denied.

P77 (2025) Movie Ending Explained:

Was Luna actually the mother?

“P77” is, at its core, a study of class struggle. Luna’s dream is modest yet crushing in its weight: to give her brother a life untouched by the precarity she inhabits. Her repeated observations about others being “lucky,” about people deserving a little for themselves, register as quiet indictments of the class divide in the Philippines. Yet her devotion carries an obsessive edge. Luna relates to Jonas less as a sister than as a surrogate mother, a distinction that quietly governs her every decision.

Natalia’s absence as a vanishing mother deepens Luna’s fractured psyche. Luna cannot imagine a version of life in which she is not the one caring for Jonas. Her mother’s unreliability and her dependence on Luna to function simultaneously as provider and primary caregiver stretch that love past its limits. The camera lingers on Luna’s gaze, framing it as a mix of longing and exhaustion, a desperation rooted in her inability to save her brother from his illness.

When the job is offered, refusal is not a real option. Accepting it slowly turns Luna into the very figure she resents: another vanishing mother. Her physical absence, compounded by witnessing Jonas’s death through a screen, becomes the breaking point, pushing her beyond the threshold of psychological endurance.

How does trauma play out in the film?

This film is a study in itself as to how trauma manifests itself. Cabrido’s reliance on an unreliable lead helps to draw out the narrativization of PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). Luna can be classified as an OFW (Overseas Filipino Worker). As an OFW, she is removed from the distress of reality. Her ability to be an earning member of the family ultimately leads to the death of her brother Jonas.

This is where her threshold breaks. The guilt of leaving her brother to perish in such a slum while she is out there enjoying the fruits of labour pushes her further into a void where she cannot mask her guilt. Her romantic entanglement with a coworker furthers the narrative of guilt. So, when she returns, she constructs the high-rise of P77. The building represents her inadequacy to provide the haven that she wanted for Jonas. Hence, she makes the building an evil space. The architecture of the building, the set design and lighting, all represent a bleak outlook that her slum also mimics.

The mimesis doesn’t stop there. She imagines the same people that she meets on the cruise, but only as evil. She considers them the enemy of the masses. Her brother dies in that squalor because of people like these who have too much for themselves. The stark socio-economic divisions which is inherent in capitalism lead her to categorize the elite as moral deviants and sexual predators. Consequently, her psychological construction of the masquerade ball and Jonas’s capture functions as a reaction to the systemic violence inflicted upon him, and by extension, her.

Her carefully constructed alternate reality is nothing more than a manifestation of PTSD. OFWs and their inability to be there for their family is a theme central to the narrative of the film. Luna’s love is monetized by disenfranchising her from the situation that she needs to be in. Capitalism’s greatest victims are the poor. The need for capital to survive while simultaneously becoming the reason for her brother’s death is too much for Luna to deal with. Hence, her alternate reality becomes the space where her brother is still alive.

Why does Luna choose to become better?

Cabrido’s slow-burning horror drives Luna toward acceptance, though the film remains acutely aware of how limited that acceptance can be. There are countless ways this story could have ended, and while an ending rooted in acceptance functions cleanly at the narrative level, it carries little thematic consolation. Luna’s horror upon realising that the world she constructed was only a figment of her imagination is stark and unforgiving. What remains untouched is the larger terror: there is no escape from the structural inequalities that shape her life.

Even as Luna comes to terms with her brother’s death, there can be no comparable reconciliation with the conditions of slum life. Cabrido offers no illusion of harmony or moral balance. Instead, he stages an ending that demands Luna let go of Jonas while leaving systemic injustice firmly in place, an inescapable constant of her lived reality. Her decision to “become better” signals less a transformation than a reluctant return to a world stripped of the emotional shelter caregiving once provided. Ted Lasso’s line, “It’s the hope that kills you,” captures the film’s undertone with unsettling precision. The expectation that circumstances will improve, or that endurance alone will lead to healing, is precisely what renders the film horrific.

Luna hopes for normalcy and reaches out to Theo, asking to see him before he boards the cruise. Classical storytelling has conditioned audiences to read such gestures as signs of closure. Cabrido exploits this expectation, only to undermine it. By framing acceptance as an act of letting go, the film exposes the unresolved guilt beneath Luna’s composure. Her acceptance operates less as a genuine resolution and more as a narrative endpoint, offering emotional closure without gesturing toward systemic change.