Lars von Trier is one of those directors whose name evokes extreme responses. People seem to love him or hate him. What can be said for sure is that von Trier is an iconoclast who has questioned, defined, and redefined cinematic trends. It’s worth of note that this is not just with respect to visual style but also his approach to writing, sound, narration, and working with actors. As we advance through his filmmaking career, we see the evolution of the von Trier camera from tripods and rigs to handheld and free of mechanical shackles. Von Trier’s films are very fascinating to examine because of his casting approach and the ability for set energies to transcend and reflect in his films.

His films tend to magnify the human condition and often deal with themes of birth, death, pleasure, and pain, among others. Inspection of these happens through action, narration, and montage, and it’s at the intersection of these modalities where the film can become a highly personal experience. This distinct audio-video play is something we now ascribe to as being characteristically von Trier. Many of his films are often called out to be unsettling, mostly because of their psychosocial and psychosexual underpinnings. In this sense, von Trier’s films are an atlas of the human and the inhuman, with plots and circumstances in his films serving as forks in the map of values.

Below is the list of All Lars von Trier’s films ranked in descending order:

14. The Boss of It All (2006)

Jens Albinus plays a stand-in boss in this Lars von Trier film. Albinus’s character, a struggling actor, is hired by Ravn (Peter Gantzler), the owner of an IT firm, to make hard decisions on his behalf while playing along as a head from the US branch. Soon, the “actor-boss” takes to his role with gusto, instilling method acting and seriousness in his “performance.” However, the lines between the act and the real blur, and before we know it, the boss is well into the company’s feelings and making decisions for its people. The Boss of It All is Lars von Trier’s continuation of sardonic filmmaking, albeit this time it’s about the corporate world.

The claustrophobia of the office, mind-numbing jargon, and stifling bureaucracy is amped up and presented as a deadpan comedy. The Boss has some characterizations of Michael Scott (from The Office). The meeting scenes in the film are also reminiscent of the meeting room instances from The Office franchise. Lars von Trier indulges in this film by having narrations and meta-references to his own films and filmmaking. The humor is modulated for most parts of the film but can get on the nose at times, especially the ending, which is evidently over the top, aimed to create a theatrical completion. The Boss of It All is more office than most office-based films, keeping its reality and shenanigans intact. However, von Trier’s self-referential treatment dials down the intent of the film, making it seem like an immense parody even when there is much more in scope.

13. Images of Liberation (1982)

Images of Liberation is Lars von Trier’s graduation film from the National Film School of Denmark. Set in the time of WWII and the post-occupation of Denmark, the film includes narration, montage, and a distinct color palette. This time it’s red followed by sepia (a similar sepia brown which would be replicated in The Element of Crime). There are focus shots of fires and lanterns to instill the tone of the palette. While the film is a love story of a German officer meeting his lover, there are transitional sequences of war, longing, and peace.

In most of these sequences, there is a voiceover narration, a style von Trier would employ in many of his future works. The camera is stationary and moving and characteristically slow, like a faint breeze whenever it moves. This gives the film a distinct stillness, which is seen in von Trier’s pre-Dogme 95 films. This characteristic camera is also very Tarkovskyian and much of the film seems inspired by the director’s oeuvre. The open setting with a forest backdrop and tracking of birds towards the end of the film is also reminiscent of the Russian auteur. Images of Liberation gives us a glimpse into the mind of the young von Trier, an introduction to his cinematic dictionary, and his essayist style of storytelling.

12. The House that Jack Built (2018)

Lars von Trier’s most recent feature is the slayer flick The House that Jack Built. By the time we get to The House that Jack Built in von Trier’s filmography, we’re well versed with his language: chaptering, narration, and the works. For new Trier viewers, the film has shock value and a decent amount of philosophical meanderings done in a way that prods the viewer’s moral compass. Jack (Matt Dillon) in the eponymous film is a character we learn to hate almost immediately as the film begins as he starts taking his victims in quick succession. The killings, chaptered as incidents, happen with the backdrop of Jack being led into the circles of Hell by Verge (Bruno Ganz).

The film is gruesome, to say the least, and one of the major problems is that Jack’s own understanding of himself supports each incident, as an architect, his shortcomings, and how the incidents help him become close to his grand enterprise in life. Watching the justifications is hard; the film feels like a visual dictionary of evil. In terms of his physicality and gesturing, Dillon’s Jack is similar to Mark Duplass’s serial killer in Patrick Brice’s Creep. The subterfuge, coldness, and the super-faith they carried are similar, yet Creep is a much more watchable film and doesn’t feel like being strapped on a chair and given the Ludovico treatment.

11. Epidemic (1987)

Lars von Trier’s second feature stars himself and Niels Vørsel (also his co-writer) as collaborating scriptwriters who’ve lost the only copy of their script. The film is about the events that follow, over five days, in which Lars and Niels write a completely different script than what they started. This “rewrite” is about an epidemic that takes over the city and its inhabitants. And, similar to how the script and its contents will witness inexplicable coincidences, the plot and events mirror and monitor similar events in real life, in which a highly infectious illness has begun to spread.

While shots of people speaking while the camera looks elsewhere were seen in Images of Liberation and The Element of Crime, juxtaposed imagery, which von Trier would use in the future, is seen in Epidemic. ’A film ought to be like a pebble in your shoe’ is something Lars toasts to in the film, and this is quite literally the tone that is set in most of his films. Characters, dialogue, and visuals that are unsettling are typical von Trier characteristics that can be found in abundance in Epidemic.

The film alternates between conversation and spectacle. The scenes with Lars and Niels appear personal, shot like a home movie (about a couple of friends) with close-ups. In contrast, the sequences with the epidemiologists tracking the epidemic and the doctor helping people in the parallel track have a more structured cinematic treatment with planned shots and an accompanying score and have an air of importance. This clear distinction evokes a feeling of the cinematic versus the non-cinematic, implying that we recognize certain visuals and accompanying treatment as more cinematic than others.

10. Antichrist (2009)

The film starts with a passionate lovemaking scene between a married couple (Charlotte Gainsbourg and Willem Dafoe’s unnamed characters). It’s an operatic montage and arguably one of the best von Trier intro prologues (yes, Antichrist is chaptered as well). Usually, tragedy befalls a von Trier film quite soon into the plot. However, here, we’re given something even earlier. As the couple forgets themselves in their intense tryst, their baby crawls out of his rocker and watches the parents fornicate. However, he’s more interested in the heavy white snow falling outside and moves towards the open window and falls. The loss of their child affects the couple, more so for the mother, who is grieving intensely. The husband, who is a therapist, takes to her case, and they move into a cottage in the woods for therapy and recovery.

It’s from here that the film further veers into darker territory. The change, of course, is into Satanic lore, with parasitic and carrion imagery foreshadowing the approaching nether. Subsequent sequences of psychological and physical trauma, though purposeful, are distracting and drive the film away from its conscious themes. Like Nymphomaniac, one of the other two films in von Trier’s “Depression Trilogy,” Antichrist tries to pack in too many things. The second half feels like an ensemble directorial venture. Sequences of horror and harm are akin to a thematic mishmash of Ari Aster-Rob Zombie filmmaking. There are numerous references and imagery in the picture that appears in Melancholia and Nymphomaniac, making Antichrist only work better as part of the thematic trilogy. Otherwise, it’s a film with too many morbid oddities and little value as a standalone feature.

9. Nymphomaniac (2013)

Narratives of extremes, of aberrations, have a reputation for evoking emotional and personal responses from their audiences. Nymphomaniac is such a story, a narrative of Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg, Stacy Martin) with her exhausting inventory of sexual experiences, who describes them to a bookish sober man, Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), who takes her into his house after she is assaulted. Thereby starts a discourse of Joe’s self-diagnosed nymphomania and Seligman’s various ways of looking at her course of life, prodding and adding fuel for continuation. The film is divided into chapters, excerpts from Joe’s life, her “symptoms,” her amours, and the chronic foreshadowing of her “condition.” In a scene with a Rublev-styled painting of baby Jesus and Mary, Joe describes, “look how flat it is, it has no perspective.”

Similarly, Nymphomaniac doesn’t have any perspective, rather, it develops too many only to collapse to nothing. The film ebbs and flows in its perpetual interpretation of everything, experiences analogized using everything under the Sun, from the transfiguration of Christ to air drafts to Fibonacci numbers to Prusik knots. Some of these are accompanied by what is now an uncannily von Trier style of moviemaking, the video essay interludes – segments of cinematically explainable shots supporting the narration. The dialogic structure and the cinematic segmentations are also seen in von Trier’s newer films, including The House that Jack Built. Though the film flirts with some interesting thoughts, including societal hypocrisy and abjuring empathy, they are never fleshed out to their potential and just become part of a broad philosophical chatter.

8. The Idiots (1998)

The second venture of the Dogme 95 movies, The Idiots, follows a group of individuals searching and conjuring their “inner idiot.” This isn’t the Scandinavian Dumb and Dumber or the mockumentary-styled Jackass about a bunch of people acting out repulsive physical movements. The Dogme 95 Manifesto doesn’t allow much room for technological intervention, and as a result, the films mostly revolve around characters, and the plot is progressed through character speech and action. Lars von Trier’s Dogme debut is effective in carrying the story through the idiots, listing out their transgressions, their addiction to the ideology, and the effects of their socio-intellectual separation.

Like the non-auteur emphasis of the Dogme 95 movement, the Idiots is a people’s film. The cast list is long, and each of them plays a role that creates a domino effect on the film’s structure. The film cannot be termed as an exercise in absurdism as Trier has incorporated multiple such elements since his first feature. The unsettling and borderline crass sequences make us want to classify it as such simply because of our conditioning, and perhaps Trier is provoking the audience due to this very conditioning, an aversion to questioning structure and tradition.

7. Melancholia (2011)

A rogue planet is going to collide with Earth. A woman spiraling out of reality. A mangled wedding ceremony. Melancholia is Lars von Trier’s big disaster film. Justine (Kirsten Dunst) is a bride on her wedding day who pursues a series of distractions and events that lead up to her personal dismantlement. She cheats on her fiancée, belts out a diatribe at her advertising firm boss, and calls off her marriage. Justine’s story mirrors Melancholia’s (the planet) course. As the film progresses, the planet’s path and eventuality become clearer to the viewer. Justine’s helplessness and inability to grapple with herself are evoked by the impending doom of the planet crashing into Earth.

The film is rife with references, especially in an easter egg sense. Art is aplenty, with Millais’s Ophelia (who eventually drowns in Hamlet) and paintings by Bosch and Malevich making appearances, amongst others. Melancholia has two halves, the marriage day and the days after. Justine stays in the castle of her sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and brother-in-law John (Kiefer Sutherland). Their collective interaction with the planet’s future visualizes the different shades of hope. Melancholia is a tragic opera in design, with the characterization, use of Wagner, and structural arc. Lars von Trier pulls off a sight and sound experience with this one.

6. Manderlay (2005)

The film begins where Dogville ends. After her father and his band of gunmen have burnt Dogville, Grace (Bryce Dallas Howard) with her father (Willem Dafoe) and team continue on and stumble upon an Alabama plantation called Manderlay where slavery is still practiced. Similar to Grace in Dogville with moralistic concerns, Grace in Manderlay takes it upon herself to emancipate the slaves. The story follows a structure similar to its previous film, and there is an arc of concern, organization, realization, and escape. What is particularly interesting is the choice to have a completely new cast for the sequel. Dallas Howard’s Grace is much different from Kidman’s Grace, yet similar in many aspects. The dissimilarity stems from the performers’ ability to bring their own energies to the characters, whereas the similarities stem from the script and the production setup.

In a way, the physicality of Grace is defined by her characteristic fur-collared coat, short haircut, and headband. Grace, as an individual, is created by the people around her, their inflictions, and her changing epistemic compass. The assumptions made by Grace in structuring the community and its subtle fatalism are remindful of Buñuel’s Viridiana. Unlike Viridiana, however, there isn’t much clarity on the degree of success or failure of the eventuality of Grace’s intentions. In von Trier’s style, John Hurt induces and explains the non-specificity through his narration, guiding us through the psyche of the townsfolk on Manderlay.

Watching Dogville and Manderlay back-to-back can bring out some interesting comparisons, though spacing out the viewings in time has a hangover effect, with the characters from Dogville looming about like specters, almost possessing the fresh cast, and this “new but old” setting readies us to anticipate and understand a tale of freedom, structure, and its collapse in an intense way.

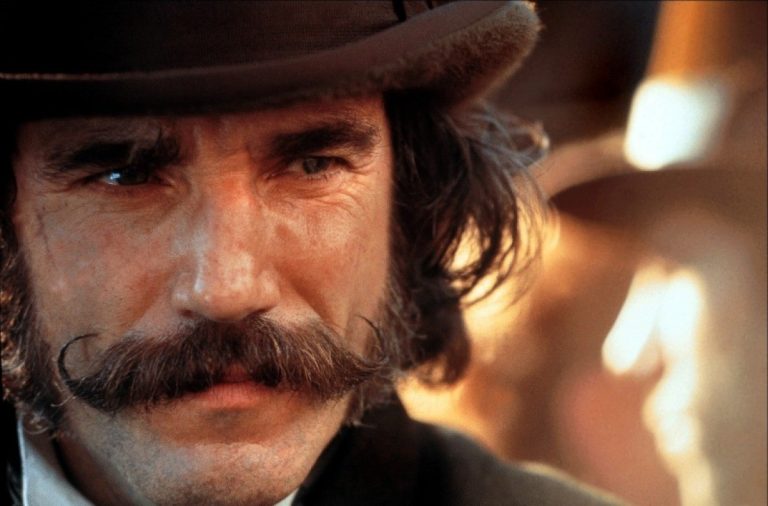

5. The Element of Crime (1984)

The Element of Crime is Lars von Trier’s debut feature and one of his most stylistic works. The film is a Kafkaesque tale of a detective (Michael Elphick) and his mysterious case. The Element of Crime operates in a Lynch-meets-Tarkovsky-meets-Jodorowsky world and is a complete trip in thought and perception. Like how most of von Trier’s films include sequences that remind us of those from many other iconic films and director styles, The Element of Crime is no different. Scenes of detection are done like a Hollywood movie in Michael Curtiz style. At the same time, crime and criminals seem to be inspired by George Miller’s Mad Max films, and the mutilation and autopsy scenes appear to be from a Cronenberg thriller-horror.

The film is a cinematic potpourri similar to recent films that work in an analogous space, including Rodriguez and Miller’s Sin City and Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night. While The Element of Crime is a supposed “murder mystery,” it’s much different from von Trier’s trauma core films, and violence here is embedded into the plot as opposed to the plot revolving around the very theme. Fisher, the detective, is tracking an elusive Harry Gray and uses The Element of Crime, a text written by his mentor Osborne (Esmond Knight), an outline of crime and expands on the theory of effective detecting to track him down. The deeper Fisher delves into the methods described in the book, the better he knows the crime while assuming the perpetrator’s mind. This neo-sepia thriller is unlike von Trier’s other films and makes for a mysteriously engaging watch.

4. Breaking the Waves (1996)

The film starts as a sweet love story, opening with the marriage between Bess (Emily Watson), a virtuous Scottish woman, and Jan (Stellan Skarsgård), a confident oil rig worker. In true von Trier style, happiness is short-lived, and Jan meets with an accident on his rig. Bess and Jan’s matrimonial beginnings are halted, their discoveries of each other through love and lovemaking abrupt, and a waning connection remains. The moribund Jan prophesizes that the only way for him to live is to love Bess and for her to love him back, for which she’ll need to feel physically and sexually close to him, which can be achieved by her finding other male partners. After some resistance, Bess takes this absurd beckoning as a spiritual message, often citing her disturbing actions to the larger cause of saving Jan.

As the film moves into its later chapters, cut-out by magical stills and good old Jethro Tull-Procol Harum-Elton John… interludes, the film starts demarcating two realms: Bess’s “spiritual” gleanings and the assumed reality (which the other townsfolk operated in). Jan’s character also has his own transitions, from supporting Bess’s journey to doubting his own prognostication. Jan even wonders if people turn bad when they are on edge, on their deathbeds, clouding their judgments. Even Bess’s introspections are pronounced by von Trier, with scenes where Bess is having a verbal dialogue with her inner God, often self-affirming that she and her love is being tested and that she needs to continue reinforcing her spiritual connection with Jan. Breaking the Waves is an ambitious film, with its etiological questions giving rise to constructed theology and its eventual disintegration.

3. Europa (1991)

Europa arguably has von Trier’s best introduction sequence, which forms an important part of most of his features, and is an inspiring expansion on hypnosis and establishment. Leopold Kessler (Jean-Marc Barr) is a train conductor in the Zentropa train company, an American working in post-WWII US-occupied Germany. Kessler goes through routine training, works earnestly, falls in love, and does what he is told to do. Soon he realizes that his job as a sleeping car conductor is a setup and that he is a pawn in a larger reactionary game.

Through Europa, Lars von Trier depicts two dystopias: one of the physical ruin and afflictions of war and the other of the psychological and non-physical ruin of the human. Both are visually obvious, with the latter being about the humdrum of work, the absurdity of bureaucracy, and the inconspicuous construction of identity through organizational compliance. The dingy first-class cabin is a reflection of the confused mind of Kessler, who does not know which side he is on. Being part of a trilogy, Europa is a different film in comparison with The Element of Crime and Epidemic.

Surrealism is toned down, and unlike the other two films, the intent and motivations of the characters are easily accessible and understood. It would be a grave error not to mention that Europa is amongst the best train films ever made. While the physics might not match up when compared to the more recent hyper-real cinema (boosted by technological progress), we are effortlessly transformed into the compartments, its sights and smells, and the sooty engine chugging along the steel frames. The movement of the film is accentuated by the movement of the train, an unstoppable force in constant motion. It is really something bigger than the workers and the passengers which comprise it, mirroring the ideologies which are cogs in an ever-expanding collection of metanarratives.

2. Dancer in the Dark (2000)

Selma (Björk) is a single mother, a Czech immigrant working in a factory in the United States. She and her son suffer from a (possibly genetic) degenerative eye condition that requires an operation. She is running out of time, the walls are closing in, and she needs to save up fast for her son’s operation. Dancer in the Dark is a story of intrinsic societal inequity. It’s one of the few films by von Trier wherein there are black and white characters, and not everything is centered around the spectrum of grey. The film has a grand ensemble cast, with Catherine Deneuve, David Morse, and Peter Stormare playing prominent roles.

These characters’ interactions with Selma add a layer to our understanding of her, whether it’s empathizing and supporting her through her battle or cheating and inflicting pain on her. While the film is primarily classified as social realism, it’s fascinating to see how von Trier employs musical passages to elevate each of Selma’s turning points, emphasizing the significance of the situation. The sequences are also spaced and structured in a way such that the finale is an emotional thump, leaving us despairing and thinking of the tragedy well after the credits roll. Dancer in the Dark is von Trier’s most accessible film and makes for a great introduction film to his filmography.

1. Dogville (2003)

Dogville is Lars von Trier’s grand enterprise of minimalism. It is set in the eponymous town (read large warehouse) with boundaries demarcated in white paint. Each plot in the town is tagged and needs to be imagined as a constructed infrastructure. Doors can be heard (from the knocks) but are not present physically. While it is simple to conceive of Dogville as a live play, the symbolisms are more effective when viewed as a surrealist production, and Dogville’s subversion is visible in this realm. The film starts with an explainer of the town and the introduction of Tom (Paul Bettany). Tom is a procrastinating writer but is mostly consumed with his role as Dogville’s self-proclaimed philosopher. The film is chaptered, and in the starting, one after the prologue, we’re introduced to Grace (Nicole Kidman), who is connected to a gangster enterprise and is found fleeing from them near Dogville.

Tom warns Grace of the treacherous mountains and that she should seek refuge in the town. The townsfolk doubt Grace, which makes Tom call for a period of two weeks to convince them of her worth. After the specified period, a plebiscite is held, and Grace is accepted. However, the widespread approval fades after a while, and Grace is forced to earn her way back. This is when the film begins to build a moral dictionary through the acts of the townspeople, Grace’s experiences, and Tom’s philosophy. Grace’s inner journey happens alongside that of Tom’s. Grace’s awareness undergoes a metamorphosis, culminating when she orders the mob to perform actions during the film’s conclusion. Themes of doubt and introspection are articulated visually and form the basis of Dogville, which otherwise is pictorially bare. It’s the beliefs and actions of the characters of Dogville which is the infrastructure of the film.