The British Film Institute is renowned for not only bringing new voices to light— through the BFI Academy and Future Film Festival—but also for preserving old ones. The BFI National Archive ensures hundreds of films from every corner of the globe and era in history remain accessible and restored by many talented specialists. It makes sense, then, that the 67th BFI London Film Festival should include Ehsan Khoshbakht’s documentary Celluloid Underground (2023) – a homage to cinema and, more importantly, its preservation.

The 1970s were a turbulent time for Iran, as the decade ended on the heels of a revolution. Before this, avid film collector Ahmad Jorghanian hosted film screenings for all to attend. But following the 1979 Islamic Republic referendum, the Iranian government only had one thing to say about cinema: destroy it.

Although some—heavily censored, Iranian produced—movies were permitted to screen, young Khoshbakht spent most of his childhood staring at a “never-ending still image of a flower,” which preceded a Quaron reading, and then back to a signal-less blank space. Khoshbakht interweaves this floral still throughout Celluloid Underground, reminding us how fragile his—and possibly our—freedom is. Even as a child, Khoshbakht was aware that his entire country, religion, and culture had been reduced to the noise of TV static. There, he watched on ceaselessly, desperately, for an escape out of the black-and-white bars and into an MGM musical, like Dorothy stepping into Oz.

For Khoshbakht, cinema fell into its most age-old function: escapism. In his war-torn city, the “heroes of Monday [were] fallen by Tuesday, executed by Wednesday.” Khoshbakht wished only for the place where “dreams were invented,” seeing filmmaking in the same magical light that George Méliès did a century before. As Khoshbakht grew up, his TV-screen-sized window of escapism grew into a political statement, something he was willing to risk his freedom—his life—for.

Film clubs are a standard part of every university, but Celluloid Underground enlightens us on how much we take this for granted in the West. In most places, films and TV shows are background noise or easy-to-reach entertainment, but in post-revolution Iran, it was “a fragile film utopia,” one that Khoshbakht helped build by running film screenings outside of the law.

Khoshbakht repaints the past through old film footage—footage that has the spirit of the 70s etched into its film grain. The opening photographs of his abandoned childhood cinema have a haunting quality reminiscent of found-footage horrors, followed by real horror footage of the street violence bred in the Iranian revolution. Celluloid Underground is truly an ode from the heart of its director, who recreates scenes from his life using real movie clips. For him, his life is interchangeable with the movies; it is the only language he knows to explain or understand his own existence, “feeling like an overexposed film” and “dreaming celluloid dreams.”

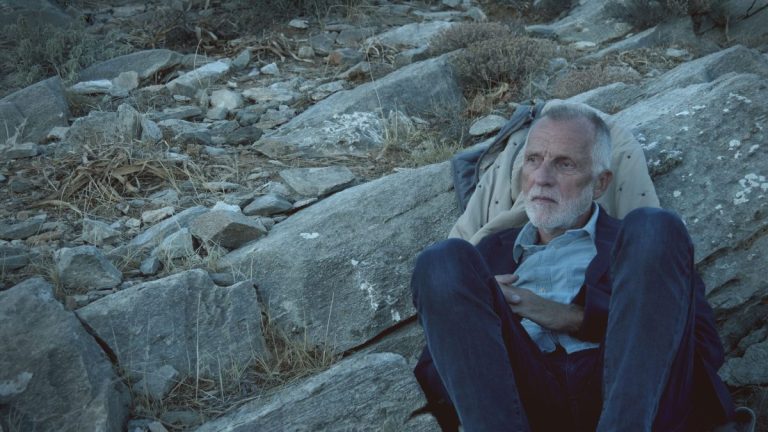

Khoshbakht moves away from his own life and the context in which he found cinema and onto his part idol, part friend, Ahmad Jorghanian. By the time Khoshbakht had left university, Jorghanian was living alone in his celluloid-filled basement, having served prison time for his movie collections (ones he describes almost paternally, stating that “I’ve taken care of my films, and I will continue to do so,” in defiance of the law.) Khoshbakht invites us to sit in on his conversations with Jorghanian, rifling through his vintage movie posters and 16mm reels, which he collects on an obsessive level.

For a man whose whole life is intoxicated by cinema—bordering on the addictive, his home stacked with piles of film and memorabilia like an episode of Hoarders— Jorghanian’s understanding of it is strangely askew. His film history is half rooted in fact, half fiction, and as Khoshbakht puts it, he has an instinctive view of cinema rather than an informed one.

For all of Jorghanian’s impassioned cinephilia and Khoshbakht’s poetic narration, there is a melancholy tinge to the images in Celluloid Underground. In place of human connection, Jorghanian has his projector screen, and not long before his death, Jorghanian admits that he wished he’d had a family of his own. After visiting Jorghanian’s crowded basement home—giving the title Celluloid Underground a literal and metaphorical meaning— Khoshbakht heeds his friends’ regrets as a warning for his own life.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) was the first film that Jorghanian shared with Khoshbakht, and after Jorghanian’s unexpected death, Khoshbakht searched for clues in the John Huston Western. The character’s obsession with finding gold mirrors the obsession of Jorghanian—and, to a lesser extent, Khoshbakht—for his films. Ultimately, “the gold has gone back to where we found it,” and Khoshbakht learns not to fight against the loss of precious film negatives but to accept it as part of the life cycle. The same way you accept the death of a loved one, knowing they live on, immortalized, in memory.

In recent years, movie theaters have fallen away to the age of online streaming, making people claim that cinema is finally dead—or about to be. Yet, if the movies can endure the laws of a harsh Iranian government, who torture the likes of Jorghanian that are determined to preserve it, if “cinema got illuminated” even in the cracks of Khoshbakht’s crumbling childhood theatre, with the smell of pickles and gasoline in the air, surely it can withstand something as hollow as Netflix?

Khoshbakht revisits his story for Celluloid Underground following the loss of Jorghanian after buying a one-way ticket to London—the same London that Alfred Hitchcock left behind and the same place we were introduced to at the beginning of the documentary. A place where you don’t have to wait for the jump-cut between lovers. A place where “the kisses stayed.”

“Farewell, Ahmed. See you on the screen.”

![The Seventh Continent [1989]: A Critique on the Emptiness of a Quotidian Existence](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/The-Seventh-Continent-3-768x456.jpg)

![John Bronco Rides Again [2021]: ‘Short Film’ Review – Walton Goggins Returns As The Greatest Fake Pitchman](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/John-Bronco-Rides-Again-2-768x448.jpg)