How does a protegee pay tribute to his mentor? Would it acknowledge the possible differences in opinion with the mentor that nevertheless sparked an intellectual firestorm in the protégé? As it turns out, Anjan Dutt’s Chalchitra Ekhon strains to render a facsimile of Dutt’s relationship with Mrinal Sen, which is aplenty in affectation. Dutt’s imitative urges by way of recreating scenes from Sen’s films only serve to strip the film of propulsive dynamism. Worse, Dutt tries his hand at Sen’s freeze frames that come off as awkward and oddly positioned in their choices.

Dutt opens his film in the years he was a fledgling theatre director who often went against the tide of Bengal’s then ruling leftist dispensation. Ranjan ( Shaon Chakraborty, who occasionally exaggerates Dutt’s over-excited gestures and mostly just wears a very glum expression), the Dutt figure, has the patronage of the Goethe institute in producing and mounting his plays, but the Bengali intelligentsia is sharply opposed to his work that isn’t shy of its cynicism about Marxist agendas and the promised revolution.

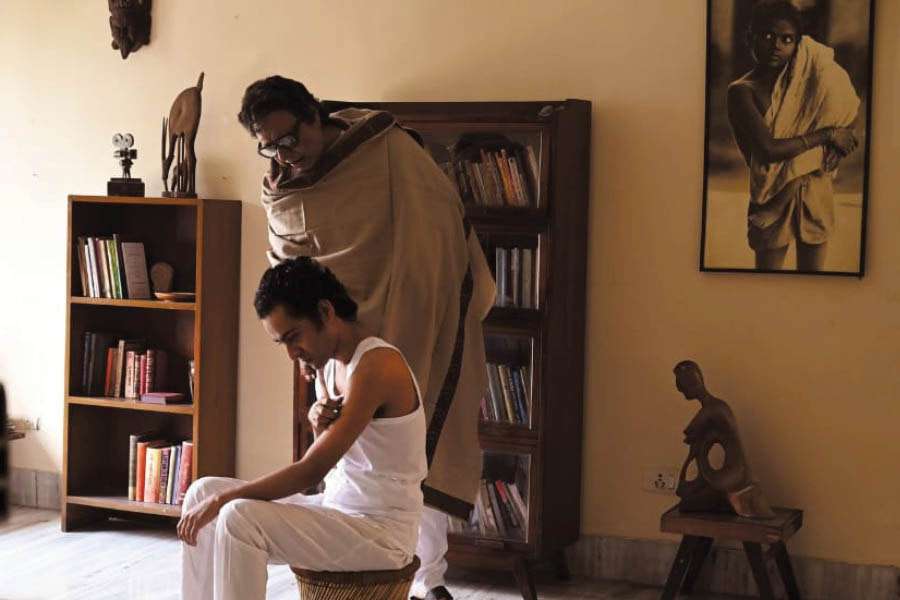

Ranjan is cobbling together a production of Peter Weiss’ Marat/Sade when he goes to interview Kunal Sen at his house (Mrinal Sen figure, played by Anjan Dutt himself) for his article in the newspaper he is a reporter at. Sen had already by then cemented his status as a titan of world cinema, but his films weren’t greeted with such a similarly generous reception by the masses back home. Therefore the young Ranjan isn’t so enthused about meeting Sen and admits to seeing just a handful of his films, nevertheless mentioning his particular admiration for Calcutta 71.

Ranjan came to the interview with fairly limited expectations. As he confesses to Sen, he imagines it as just a brief snippet. However, Sen’s passionate, lively curiosity broadens the interview, digging out more than what Ranjan necessarily had in mind. However, a lot of the film, including this scene, is wholly undone by clunky dialogues that lean either towards the declamatory or extract comic relief. Sen exclaims he is excited by and disappointed in Calcutta, irritated and fascinated with it; an entire list of conflicted emotions is doled out.

A painfully grating staginess exacerbates the flow of scenes. Dutt’s peculiar approach to the film makes the film tilt towards being awfully conscious and artefact-level wooden, divesting it of immediacy and bristling electricity that should have surrounded Ranjan’s dilemma and his relationship with Calcutta.

The film shuttles to Ranjan’s rehearsals with his group. He is mostly exasperated with them and eager to escape to Germany and find work there which his superiors at Goethe had promised they’d ferret out something for him. Ranjan comes across as an individual bursting with ideas but who feels limited by the city and the ambit its cultural custodians have set. He is a bundle of nerves, constantly jumpy and restless to get his due, which he is confident this city cannot give him. While the screenplay thankfully amply gestures to Ranjan’s privilege as opposed to those he is constantly hectoring for lowering the standard of his artistic vision, the way Dutt chooses to go about cranks it out through a messy fight, culminating in Ranjan’s belated realization about his more advantageous social position.

The rehearsal scenes add little to the film, and I wish Dutt reserved some scope for the women both in Sen’s and his life, who have steadfastly stood behind them. Bidipta Chakraborty is absolutely lovely as Sen’s wife, suggesting a quiet strength in the few scenes she has. Spanning the weeks Ranjan shoots for Sen’s eponymous film, Chalchitra Ekhon is structured around his decision to leave for Germany. Dutt refracts it through his attitude and how he looks at the city as it changes significantly once he comes under Sen’s wing. He warms up to the city.

The film takes great pains to underline this fractious relationship, but Dutt doesn’t quite manage to make a persuasive, throbbing portrait of the city. Snapshots of scenes from places scattered in and around the city are interspersed throughout the film in fragmentary fashion, and Dutt’s songs dutifully step in to articulate his complex longings for his home turf. Some of the songs are zingers, but the images culled together seem too lazy and arbitrarily dispersed in the film.

In circling the life-changing influence Sen has had on him, Dutt reverts to predictable markers, drawing out the ideological clashes and delineating how Sen and his work atmosphere provoked in him a sharp, necessary self-awareness regarding both craft and life. But these conversations are alienatingly written in a manner of almost trying to prove a point. In its efforts of enhancing and expanding one’s ideas, the film is too burdened by the obligation it takes upon itself of acknowledging the knowledge we have about Sen. But Dutt only acknowledges, rarely does he illuminate on the points of reference.

So there are dialogues directly alluding to the much-talked-about purportedly contradictory politics in Sen’s oeuvre that trigger a heated argument between Ranjan and his friends in a clumsily executed scene. There’s the legendary cinematographer and Sen’s regular partner, the KK Mahajan figure lecturing Ranjan on overcoming his issues regarding his appearance and how searching for truth in ordinary people matters paramount. While Arghyakamal Mitra’s editing keeps things brisk, there’s a lingering slightness to the film. Dutt delivers a commanding performance, but the film keeps rushing through things it should have measured more deeply.

At one point, Sen tells the perpetually pissed-off, crestfallen Ranjan how when he calls cut, the world seems to crash on him; otherwise, during action, he is always teeming with energy. I kept looking for flashes of interiority, a clearer glimpse of his roots, an excavation of his anger that erupts in the fights, but the film strangely lets it stay repressed.