If you go to see “Eno” (2024), you will watch a completely different movie from the one I saw. I myself have seen it twice and saw a completely different movie both times. That’s not an uncommon assertion, but usually, it’s meant to be taken metaphorically, a statement about the subjective nature of art. Here it’s quite literal: Director Gary Hustwit has tried to create a cinematic analogue of the “generative music” his subject is famous for.

He shot thirty hours of original footage, sifted through another five hundred hours of archival footage, and then turned it over to an AI editing program to splice it differently each time it gets shown, broadcasting a different cut to each digital projector across the globe. According to the New York Times, there are over “fifty-two quintillion” possible different variations based on the available footage. The end result is intended as a dynamic mosaic; look away once and the pebbles shift, producing a different portrait of the same man each time.

To give an example: the first screening I attended began with an introductory sequence of Eno explaining how he makes his generative music and then giving his full name (“Brian Peter St. George le Baptise de la Salle Eno”). It then segued into Eno discussing how evolutionary biology has influenced his work. It then switched to a look at Eno in his Roxy Music years and his relationship with Bryan Ferry.

Switch to Eno looking through old notebooks of his dating back to childhood, in a room full of Chagall paintings. Switch to an examination of the androgynous look Eno and other musicians of the period popularized. Then a switch to Eno discussing a new set of theories on the social nature of music, which he hypothesizes preceded the ability to speak. Switch yet again to archival footage of Eno working on the Heroes album with David Bowie, who provides the most insightful comments on the film’s subject: he says he’s “not really sure” what Brian does, except that he’s “as much a philosopher as he is a musician.”

The second screening began with the same introduction but what immediately followed was a completely different segment of Eno discussing the impact American rock and blues had on him as a young boy growing up in rural Suffolk. The segment on Roxy Music was there but this time accompanied by an account of Eno’s time at art school. The segment of Eno working on Heroes was also present, but this time Bowie’s interview segments were omitted. There are other new segments, segments from the first viewing completely omitted, some previously seen segments occurred at roughly the same timestamp as the first screening, others were placed earlier or later. And so on.

“Eno” is a fascinating audio-visual experiment and I found both screenings exceedingly watchable. But two questions remain, the first being how well does it/they work as a movie(s), and the second being, what do we learn about Brian Eno from it? I can say that each time, I saw different facets of Brian Eno the Musician. The first gave a good sense of the Musician as a Scientist, gathering data, using models and algorithms, developing hypotheses, and drawing a consilience of inductions from biology, mathematics, and cognitive science to further the body of knowledge in his given field.

The second time gave us a glimpse of the Musician as a Fine Artist, the former painting student who has chosen an aural canvas for his abstract art, and who now regards himself as essentially a Sculptor of Sound, molding noise until he’s aesthetically satisfied with it. C.P. Snow would probably admire this particular A.I. program for identifying Eno as a man straddling both of the Two Cultures (and for that matter, Snow would probably admire Eno himself for trying to unite them). Each viewing proved fascinating, and although I found the second screening better-paced, both times I found myself entertained and yes, intellectually provoked as well.

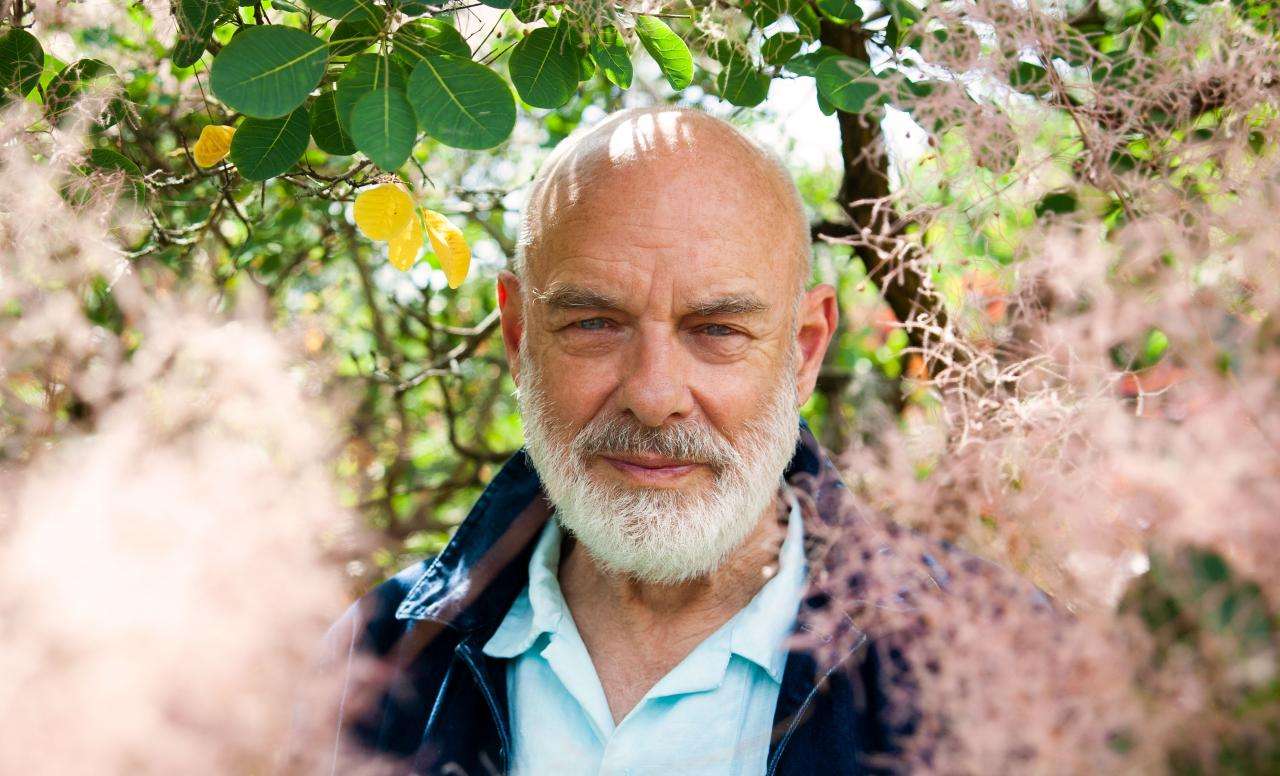

But carrying the second question further, what do we learn about Brian Eno as a person from this particular experiment? The interview segments, especially the new ones Hustwit filmed especially for this documentary, reveal an extremely bright and well-read man, but far from the bohemian eccentric one might expect from his public image. No longer in the gaudy get-ups of the past but instead sitting down in comfortable knit sweaters, V-necks, and dockers, he seems so much more relaxed than he was in the archival footage.

Eno today comes off like your most genial university professor, one aware that emeriti status is fast approaching and without worry of further review has decided to cut loose with his lectures. He’s clearly a man who has attained satisfaction in his personal and professional life as well with his musical legacy, and there’s an undeniable joy in watching him bop around his studio lip-syncing to the onomatopoeic lyrics of his favorite Fifties rock songs. He also reveals a generous streak, describing how while living in New York he’d head to Central Park to check out the buskers, searching for new talent. One such discovery, dulcimer-player Laraaji, attests to his support and kindness in helping to start his professional career.

At the same time, the fragmentary nature of this particular cinematic record with its automated malleability and shifting edits keeps us from truly understanding the complete Brian Eno …at least from just one or two viewings. It will take multiple viewings to say that it has succeeded in its mission, and it’s doubtful most viewers will have the time or patience to do so. While I felt I learned something at least semi-substantial about its subject, that may have been just luck of the draw in this instance. The very nature of this project means that for every screening there will be missing information, gaps that the audience members must fill on their own.

If you’re already an Eno devotee, it will be an easy task; if not, you’ll either have to start reading up, or just keep watching the movie over and over until satisfied. One of the finest musical biography films, François Girard’s “Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould,” used a similar collage format but under the human guidance of Girard’s direction and Don McKellar’s script (to say nothing of Colm Feore’s performance), helped to create an image of a man in full after watching all thirty-two segments. Here, the pieces of the collage keep moving, some new pieces pop in, some disappear and some reappear, so that we never get a clear enough picture.

I’m hardly an Eno fan myself, but I knew enough about him beforehand to realize a considerable amount was missing both times about his career and his artistry, musical and otherwise. For one thing, aside from a brief mention of his ecological views, neither screening touched on his well-known political activism, although no doubt viewers elsewhere did see a screening that focused on this aspect of his life at the expense of learning more about his artistic side. When discussing his time in Roxy Music, both times the film leaped abruptly into archive footage of Eno’s former bandmate Bryan Ferry presenting him with a musical award in 1994, with no mention of the conflicts over musical direction that led to Eno’s departure.

It would have been fascinating to learn more about the current relationship between Eno and Ferry, as they’ve apparently reconciled even though they’ve diverged further apart politically as well as musically. The very nature of this project means that in order to not violate any copyright laws, we only get brief snippets of music by other artists, and most of my fellow audience members expressed disappointment that they only got a few seconds of Eno working with U2 (I was equally disappointed by the complete absence of Peter Gabriel). For that matter, other than a clip from the bizarre music video for “Ali Click” (1992) not enough of Brian Eno’s own music was heard at either screening.

For both viewings, segments not only seemed strangely incomplete, but the overall structure came off as decidedly haphazard, rendering certain sequences confusing. In the first screening, for instance, one segment began with Laurie Anderson pulling a card out of a box and reading the text on it: “Take Three Steps Back.” What exactly was the point of this, I wrote in my notes? Why this impromptu appearance by another artist? Why this introduction, when there are none other like it throughout the film? And why the box of cards? Well, it took the second screening to explain it all.

The cards are from a set designed by Eno called Oblique Strategies, a form of motivator to encourage personal creativity, and there was a section at the second screening going into detail about how Eno conceived them and continues to use them. Anderson didn’t reappear at this second viewing, but David Byrne (looking very haggard and worn) did pull a card out of the box this time. Now, Hustwit very likely filmed other clips of former collaborators taking out Oblique Strategies, which in a more “conventional” human-edited documentary would serve as chapter stops but at least here comes across as not just random but meaningless.

Although the prospect of future films like “Eno” might leave the members of the Motion Pictures Editor’s Guild shaking in their boots, I would like to assure them that based on the limited evidence of this one film, the job of the flesh-and-blood human editor remains cautiously secure. Any AI editing in the near future will require the guidance of a fully-trained human professional to provide the proper prompts to ensure narrative coherence and cohesiveness. Otherwise, to call a movie a “hallucinatory experience” will take on a whole new meaning, and not a good one. The cinema, including the documentary, is essentially a rhetorical medium and while AI is swiftly developing the ability to generate verbal arguments, it’s a long way away from successfully generating visual ones in the form of motion pictures.

Still, that doesn’t mean interested filmmakers should give up or even necessarily be scared of using such technology in the future. I am certain that some brilliant aspiring writer-director will see “Eno” or even just read about it and come up with the idea for a feature film story that AI will be able to splice in a multitude of ways just as Hustwit’s project does. Filmgoers will be able to watch the same film multiple times, and each time see the story unfold in a different way, with different subplots and new characters, the same story played over and over again from multiple angles, revealing new themes even with each viewing….

Dear me. I think I may have just made a monster.

![Synchronic [2019]: ‘TIFF’ Review – Ambitious and Effective](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Synchronic-highonfilms-768x384.jpg)

![In Action [2021] Review – Bickering, self-reflective film is unbearably amateurish](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/In-Action-1-highonfilms-768x321.jpg)

![Nobadi [2019]: ‘TIFF’ Review – Questioning our notion of identity](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Nobadi-highonfilms-768x384.jpg)