The Pune-based Film and Television Institute of India was instituted in the 1960s to bring a singular voice to a young nation finding its roots. Since then, it has given the industry worthy talents both behind and in front of the camera. Social issues, and the power of images to convey them with urgency and sincerity, became the bedrock of its existence and shaped how it ultimately functioned.

Even as its governmental backlog and recent political shifts have brought students to the fora of democratic protest, the reel, imitating the real, remains its firm motto for evincing crucial truths. One of the most effective ways to showcase the storytelling prowess of its alumni is to watch the short films that populate its vast and storied archives. Right from the 1960s down to the present date, these diploma and student shorts reveal the beginnings of great careers and integrate innovative, original stories with solid performances and pacing. In honour of FTII’s official YouTube channel unveiling its restored lineup of Student Shorts this past year and beyond, this cinephile shares the top ten titles that must be watched immediately.

1. And Unto The Void (1967)

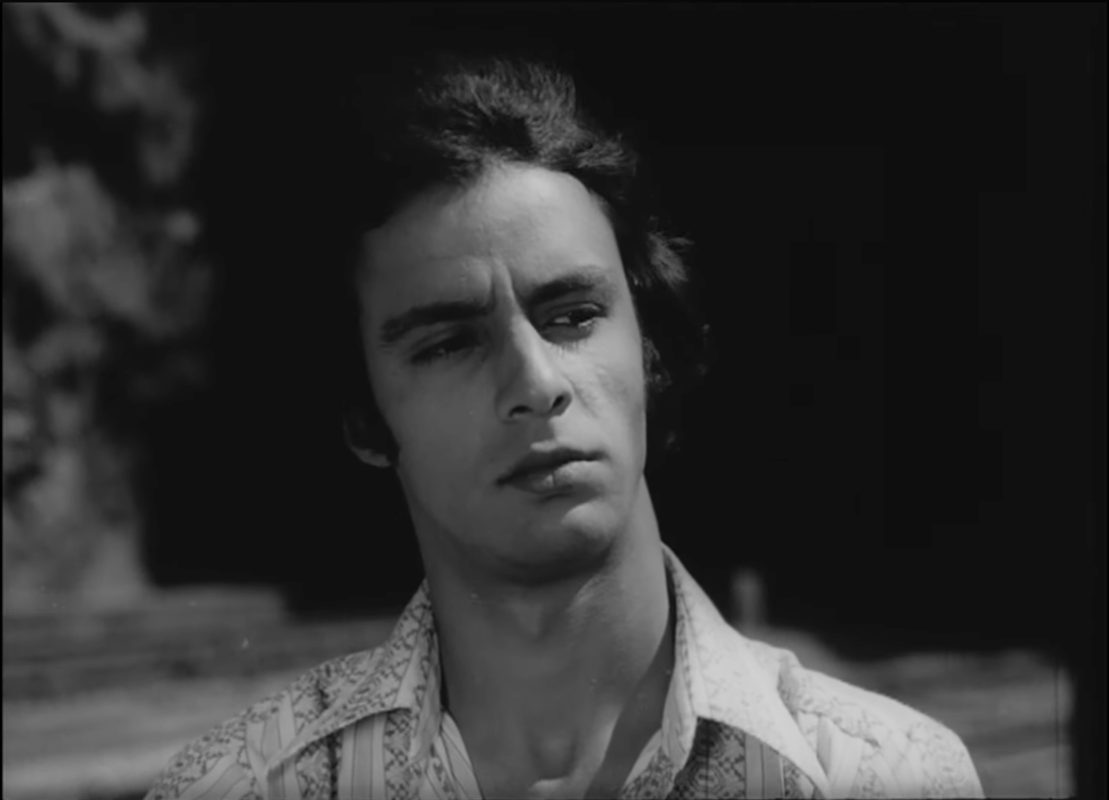

Firoz Chinoy has an astute knowledge of photographing his subjects and crafting psychological insights. He uses black and white cinematography to look into the baser instincts of humanity, where being unfaithful and incurring an impulsive man’s wrath are the seamier sides of urban living that just cannot be shirked.

Above all, it’s a showcase for Shatrughan Sinha’s impressive interiority in his early days as a performance artist. Like “Angry Young Man” (1970), another befitting later companion unraveling with his individual interiority, “And Unto the Void” proves that the legendary actor was in command of his wordless moments from the get-go.

Whether he lets his eyes do the talking when in the confines of a jail cell, shows his action credentials while hanging precariously on the side of a moving train, helplessly combats hunger by eating a piece of bread, laughs in the face of adversity and then breaks down or magnifies his close facial terrains while possibly strangulating the object of his affection, he’s brilliant.

Betrayal sets him on a dangerous path, and the noirish qualities of this short film give us a peek into his downfall when in the throes of unfortunate circumstances. If you thought he was committed to his naturalistic groove in “Mere Apne, Kala Patthar,” “Khoon Bhari Maang,” or in the parallel cinema credits of Kumar Shahani’s “Kasba” and Gautam Ghose’s “Antarjali Yatra,” look at his beginnings.

2. Angry Young Man (1970)

Shatrughan Sinha is the original Angry Young Man of the title, in a fiery show of repressed emotions brought on by illegitimacy and the intense underbelly of Bombay. Jaya Bhaduri here is trapped in this sinister underbelly where young, aspiring actresses are lured into darker corners of the city. The scene in which she steps onto the stage with the other girls, like an audition, is haunting in how it indicts a culture that demeans and objectifies women in multiple ways, trafficking their innocence before anything else.

A telling image finds her running around a beautiful garden with her dupatta splayed atop her head, in a cinematic nod to the romanticisms of erstwhile classic Bollywood imagery. The irony being that the dream visions sanctifying a freedom of being are at odds with the grim realities of the real world. When an imposing Sinha and a petite, bird-like Bhaduri embrace, their vulnerabilities become one; both dealt cruel hands by Fate.

Mr. Sinha is a saviour and enraged by the ills of his world, a victim of his fate who meets a dead-end where his hands contract and move with the impaired skills of a cobra shot dead by hunters. He’s impressively intense and uses his body language, stature, and that legendary gaze to indict society on the whole. Also, the traditional plot is stripped down to the basics, and the economy of direction is well-suited to its inner churn.

3. Suman (1970)

True to her inspired beginnings in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s wholesome family features that endure owing to their wit and interrelationships, Jaya Bhaduri is a young village girl whose innocence is her pivotal hallmark. Matching her youth with the freedom of the surroundings, she goes to a temple, joyfully watches the traditional monkey dance, picks mangoes from a farmer’s estate, meets her female friend, and returns home to her mother and younger sister. She’s mostly aimless, like every village teenager, and yet happy in her individual space.

Until a boy’s unwanted gaze breaks the spell and she returns home, not wanting to venture out with her sister. The sister goes out instead. That final image seals the impermanence of youth and innocence when sabotaged by patriarchy. In this short film, the naturalistic rhythms, settings, and sound design serve to illustrate that unseemly fact of life for every young girl who’s at the threshold between adolescence and adulthood.

Watch out for Danny Denzongpa as a village man giving children moments of entertainment. As for the always natural Jaya Bhaduri, she gets the body language and verbal patterns just right, down to the look of realisation that makes her suddenly aware of her gender amidst a world of men.

4. Teevra Madhyam (1974)

“Teevra Madhyam,” relating to a form or rhythm of Indian classical music that is sublime and subtle, is an apt title for this twenty-minute short, directed as a diploma film back in 1974 by Arun Khopkar. It marks screen legend Smita Patil’s first celluloid credit. She plays a practitioner of classical music. The first three and a half minutes expertly set the mis-en- scene where she plays her beloved instrument, settles into the mundane rhythms of the day in her modest room, and listens to the sound of commotion and a passing plane. Her stillness and facial transparency are a sight to behold.

That modesty and simplicity are revelatory of her alliance with her beloved’s (Nachiket Patwardhan) Marxist ideals. Her stillness then holds an internal turmoil as her pursuit of classical arts is at odds with the beloved’s fight for justice and protests. It is captured so beautifully in the scene where she expresses how akin to the movement for justice giving him purpose, the tanpura gives her agency & peace. However, both their ideologies cannot be symbiotic.

The core for addressing these issues is subtle, never at the boiling point, just like these young lives on the verge of change. Cue the scene where she is the lone female in a meeting presided over by party members. The long take of her changing eye movements and expressions while practicing the tanpura packs in so much of what her internal conflicts have to communicate on the surface. The vocal playback in the background befits that. She is at peace while practicing, yet knows that she may have to renounce her creative gifts for the larger cause of social consciousness.

“Teevra Madhyam” is ultimately about how women are often expected to cast themselves in a mould similar to the men in their lives, leading to them giving up their innate vocations. It is hence stirring as a generator of multiple viewpoints, even though there is no definite decision on the part of the protagonists here to choose their future course.

Read: Cinema on Cinema: 30 Great Films About Films

5. Murder At Monkey Hill (1976)

From the get-go, Vidhu Vinod Chopra was a stylist and consummate storyteller. In this acclaimed short film, he shoots the unfolding mystery from many vertiginous angles along the trail of hills, caves, bridges, and a particularly striking parting shot with a passing train.

As far as the story goes, human corruption begins this saga as a taxi ride brings us to a sunny, hilly terrain. We find that the sinister image of a young girl’s head riddled with a bullet is an endnote to an intriguing web of property dispute, contract killing, and the deceptive powers of appearances guiding two protagonists’ tryst with companionship. Gendered aggressions enter the picture, such as when a slap almost echoes across this valley.

Interestingly, Vinod Chopra is also the actor here, along with Anjali Paigankar( her New Wave credits include “Manthan,” “Sarvasakshi,” “Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastaan,” “Chakra,” and “Charandas Chor”). Together, they play a tangible game of affection and gendered toxicity. Ultimately, the images linger, and Dilip Dhawan’s axe-wielding local, another product of a social order operating on secret codes of elimination, produces ripples of menace, aiding the cinematography and musical score in the final half. The Lonavala locations are exquisitely attuned to the black and white frames. So is the presence of a moral center as Chopra breaks down and ponders his decision to betray the innocent woman who pines for him.

6. Var Var Vari (1987)

Vari is a Sanskrit word that means water and is used in the feminine sense. That way, this short film by auteur Kumar Shahani justifies its title. Beautifully photographed by Piyush Shah and with lucid sound design by K.A. Sarkar, the presence of lakes, rippling waves, inclement weather, and rain gets subsumed in a tale that gets more intriguing with each watch.

Mita Vashisht made her debut with this diploma feature. She is part enigma, part love-lorn lover, introduced as a meteorological scientist who addresses the camera directly, explaining the workings of her station while offering a teasing smile and look, as if to suggest that she is, quite literally, in control of the weather itself. Or a way of life. The sound design captures this brilliantly.

From her interactions with a wandering sage ( G. S. Chani) and then her best friend (the film’s editor, Nandini Bedi herself), she assumes the avatar of a mythic creature, a mystery figure whose lines gave me the impression that she is an impersonation of the Weather Goddess herself. She’s also a young woman who asks her friend to carry her beloved’s food across the lake, on her boat.

When more than a whiff of betrayal on both their parts is revealed, she lets her long hair be open instead of in a bun. Flooded fields close the film. It’s as if her own wrath brought an abundance of rain on earth. Maybe she manifests her emotions as the eternal Earth mother, signifying Prakriti (nature) and Saundarya (Beauty), along with their associated destructive forces.

Mita Vashisht is utterly fascinating and sensual in her portrayal here, while Nandini Bedi is more static in her dialogue delivery, reminiscent of the style of ’30s dramas. More than that, this is an aesthetically pleasing wonder, with its sepia tones ripe with beautiful imagery. Behold Ms. Vashisht by the lake, rocking a swing, dressed in her finery like a divine vision, or by the mirror, her friend on the boat, the sage amidst the verdure of nature, and the protagonist’s flowing tresses in the end. Or the image of the black swan in the first three minutes of the opening credits.

7. Reconnaissance (1990)

Irrfan Khan and Anita Kanwar’s stillness, the weight given to shared gestures like turning to face the camera or eating together at a restaurant, and the way the hills and the river’s flow form a sensual monsoon mosaic come together to make this a contemplative work of art.

Both are former lovers who occupy their own places in the heart. Irrfan is the stricken lover here whose deep eyes have the haunting quality he has always been acclaimed for all his life. With him, a bus ride and the very act of looking at the countryside become naturally intense. Every element of nature, hence, carries the weight of his emotional burden. Such is the spell he casts upon the imagery with his wordless arc, essentially pointing to the silent cinema aesthetics of this work of art.

The landscapes, blurred by the clouds, and the wind-swept aura capture the atmospherics of storytelling beautifully. Whether it’s the man drenching himself in a river’s steady flow or the vista of a hill overlooking a city bringing back subconscious thoughts, “Reconnaissance” is a visual marvel. Mr. Irrfan and Ms. Kanwar employ their naturalism sans words with overlapping dialogues in the soundtrack to find their individual rhythms of separation. The ring of the telephone, Ms. Kanwar turning towards the camera, and a crying baby become motifs that recur to paint an impressionistic portrait of the way our minds function as receptacles of our world.

Also Read: More Than Candlelight: 10 Movies That Celebrate Love in Every Form

8. Long Take Exercise (2014)

An old man sits in a restaurant. The microcosm of the world around him frames his isolation in the most telling visual manner in Payal Kapadia’s five-minute short, courtesy the Film and Television Institute of India’s storied archives. Her camera’s fluid languor catches the minutiae of sounds and conversations, including a cricket match being broadcast on television and a rainy day outside.

Mostly young people occupy this space. The camera moves with the natural rhythms of this place and the people who are situated here in their casual, carefree moulds. It’s the man’s gaze that holds his surroundings in the camera’s focal point. He observes and also realises his own place in this microcosm of life.

As the man holds an umbrella, a gym, and a delivery van further frames him as the center of the tale. Yet his silences and solitary presence speak tales of dislocation. The sepia tones are arresting. The rainy season creates an oasis of community in the restaurant, yet strikes us by the private vectors of alienation that accompany the muted whispers here.

9. Afternoon Clouds (2017)

Payal Kapadia is a sparkling sensualist. Inclement weather, horizontal interior design, and the utterly enchanting use of fumigation smoke rising like the titular “afternoon clouds” spark a masterful short film that stays true to the medium’s strengths to mine subconscious memories. Here, an old woman and her housekeeper create a naturalistic picture of codependency. Yet living in their own individual worlds, they long for connections beyond the one offered to them through each other.

The woman has memories of her dead husband. The young lady meets her beau on the staircase and muses about his note and card given to her, as well as the English words written on it. A haunting vessel of emotions or the lack thereof pertaining to their separation becomes the centerpiece of this brief encounter.

The frames are like paintings here, while the union of two generations and economy of words elevate the craft. Even the commonplace use of a mosquito net on the bed, the placement of a Liv 52 tablet pack on a side-table, and a departed one’s presence haunting a home in dreams become transcendental with Payal Kapadia’s magical touch. This is surrealism elevated to the level of understanding how isolation is a crucial fact of life.

10. Marma Bandh (2017)

In “Marma Bandh” aka “The Vulnerable Barrier,” the personal becomes universal as strains of a Kishori Amonkar vocal feat waft through a spartan home where an old matriarch (the legendary Uttara Baokar) lives alone. There’s the silence associated with dotage and widowhood. Then there’s the daughter( Varsha Dabholkar), whose desire to branch out on her own as a tutor is drowned out by a televised cricket match and an eternally indifferent spouse who discourages her with blunt sentences.

Both mother and daughter reunite in the wake of the former’s health issues. Years of inner turmoil get addressed, especially when the daughter, while cleaning her home, finds her framed college degree. She tosses it into a bin along with other unwanted nitty-gritties. Something shifts in the mother. Heart-to-heart conversations reveal the price of hasty decisions, the ghosts of a woman’s unfulfilled accomplishments, and societal frameworks that principally cost the women their selfhood as they are forced to become homemakers without aspirations of their own.

All of these are captured with lingering naturalism, where the daughter’s innate concern and caretaking ability and the two women’s consummate bond finally convey the unspoken power of female solidarity. In the end, it’s the home and the mother that accord the daughter the ultimate gift of self-actualization.

The tightly edited frames and natural lighting add to the final shot where cups of tea and snacks bring a flavour of unity that only a maiden home can accord to children, irrespective of middle age. A change is set in motion. An easy smile finds hope imparted to all those waiting for a hand of support and a voice of reason. Uttara Tai and Ms. Varsha are brilliantly attuned to their subtle inner worlds and emotional depths.