Hedda” (2025) is an earnest attempt to reimagine Henrik Ibsen’s classic story for a younger generation, and admirably avoids many of the cliches that have become inherent to modern literary adaptations. Although there is a momentum and visual slickness that feels cutting edge, “Hedda” is not burdened by contemporary language, music, or stylistic motifs.

Yet, this is a film that works in implications, as it chooses to suggest and allude to moments of intrigue that are not depicted. This is arguably why Ibsen’s masterpiece was considered a revelation when it first debuted, but that was at the tail end of the 19th century. In 2025, Nia DeCosta’s update lacks any bite, despite its inflated impression of its own provocation.

The title role in “Hedda” belongs to Tessa Thompson, whose version of Hedda Gabler is an effortlessly charismatic, yet venomous, newlywed who has grown spiteful in the wake of her marriage to the writer George Tesman (Tom Bateman).

It’s over the course of an evening party that Hedda encounters two of her former acquaintances- her former classmate, Thea Clifton (Imogen Poots), and her ex-lover, Eileen Lovborg (Nina Hoss), who has become an academic rival of George’s. Although it was Judge Roland Brack (Nicholas Pinnock) who arranged the evening’s activities, Hedda takes advantage of the social interactions to attack all who stand in her way, all whilst trickling down a path of self-destruction.

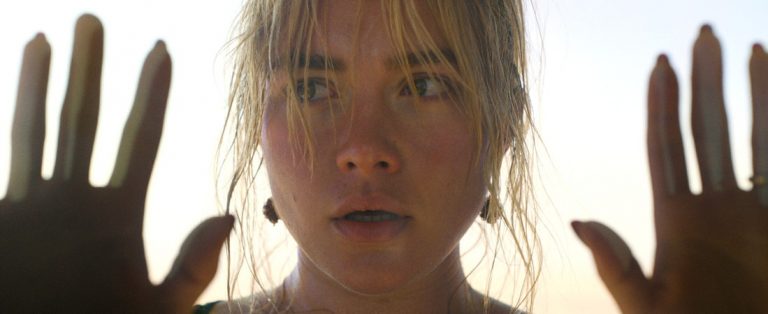

As is the case with many works of theater that are adapted to the big screen, “Hedda” lacks the immersive quality needed to make the performances feel truly intimate. Perhaps in a way of sidestepping these issues, DeCosta often chooses to isolate her characters in extreme close-ups and use a pulsating, distractingly overpowering score by Hildur Guðnadóttir to add artificial tension.

The result is a film that seems to constantly be airing on the side of friction, a tone that becomes less effective when Hedda’s remarks are meant to be more searing. It doesn’t help that the film struggles to string together its scenes in a logical manner, often feeling like a sequence of vignettes that fail to mount the appropriate tension.

Also Read: The Monstrous Feminine: 30 Best Feminist Horror Movies of All Time

Given that this is a story that has been told for over a century, it makes sense that DeCosta would want to add her own revisions in order to indicate her own authorship. Unfortunately, many of these decisions are bizarre and dramatically inert, including the choice to open the film with a tease of its tragic conclusion, as well as the insertion of a fifth act (which is denoted by the use of title cards).

The most significant character alteration is the gender-swapped Eileen, representing the character Eilert in the original text, which makes Hedda’s former flame a queer love story. Despite some subtle (and not-so-subtle) allusions to the isolation Hedda faces as a result of her identity, the film doesn’t go nearly far enough in exploring how racial prejudice and perceived gender binaries impacted this era in history.

The lack of escalation is by far the most detrimental factor in the pacing of “Hedda,” as emotions are so high from the moment the story begins that it becomes difficult to gauge the degree to which viewers should be shocked, disturbed, or emotionally affected.

Although Hedda herself becomes a more sympathetic (or at least more understandable) character as the night carries on, there’s only so much that can be credited to the revelations, which are often brushed off in favor of more elaborate scenes of discourse and debate. DeCosta has an ear for snappy dialogue, but there’s a point at which the film feels more interested in delivering clever one-liners than maintaining the internal consistency of a given scene.

Thompson’s performance is appropriately smoldering, but hollow in a way that may or may not be intentional. While a text this iconic can be feasibly adapted, the incongruous array of accents throughout adds to the aura of plasticity, which is particularly distracting in Thompson’s case.

It’s no coincidence that some of the best moments of “Hedda” are those when the titular character is sidelined and forced to observe sensitive moments of compassion that she has no hopes of replicating. This is apparent during a riveting argument between Eileen and Thea, in which the athletic filmmaking is waxed off in favor of a more authentic display of emotion.

Also Check Out: The 25 Best Movies About Writers

Hoss is by far the film’s scene-stealer, as she brings the necessary mix of righteous contempt and unpredictable depravity needed to play a recovered addict on the brink of a relapse. Of all the film’s modern insights, the more articulate understanding of the mental burdens of alcoholism helps make the character of Eileen more nuanced. Poots’ performance is also excellent, even if her more subdued approach feels at odds with many of her more scenery-chewing co-stars. While Thea’s deterioration is at times quite compelling, it’s overshadowed by the high-strung superficiality of the other guests.

On a visual level, “Hedda” is inarguably successful, as each character’s signature costuming signifies their societal status. Although the film is perhaps a little too intentional in weaving in and out of each room to soak up every bit of production detail, the design work is quite impressive, and suits the striking takedown of toxic wealth.

At no point does this feel like a desirable situation, as it’s hard to imagine that Hedda would ever be satisfied with such a banal existence, regardless of her acerbic intentions. The more existentialist moments of contemplation are few and far between, but they occasionally hint at broader societal issues that exist beyond the confines of one tragic evening.

“Hedda” is certainly bold in its reinventions, but emphasis is often put in the wrong places, with certain characters and plot points feeling underserved. Even if “Hedda” was given a muted theatrical release in order to qualify for awards, it shares the hallmarks of many streaming films. While compelling when reduced to a collection of clippable moments, there’s little that would prove more rewarding on a subsequent viewing. “Hedda” is rarely boring and often quite lively, but given the strength of its source material, that’s a fairly low bar to clear.