Memory is never merely a static archive of the past; it is a dynamic process of meaning-making, one that constantly negotiates the relationship between who we were and who we are. As Emily Keightley observes, “Remembering is an active reconciliation of past and present. The meaning of the past in relation to the present is what is at stake here; memories are important as they bring our changing sense of who we are and who we were, coherently into view of one another.” This conception of memory foregrounds its performative and situated character: remembering is not simply a private psychological act, but a culturally mediated performance, deeply rooted in social, historical, and material contexts.

In both individual and collective terms, memory plays a crucial role in shaping identity. It is through acts of remembering that we construct narratives of selfhood, reconcile trauma, and negotiate belonging. Memory is also deeply entangled with affect, it brings with it not only facts and images but feelings, desires, absences, and wounds.

As such, memory is not always a site of coherence; it can also be a space of fragmentation, distortion, or repression. The act of remembering, then, is inherently political: what is remembered, what is forgotten, and who gets to remember are all questions shaped by power, positionality, and context.

Memory, as both a biological function and a philosophical construct, has long fascinated filmmakers across the world. Through visual storytelling, soundscapes, flashbacks, and temporal shifts, cinema does not merely depict memory, it enacts it. It mirrors its distortions, its hauntings, its gaps and ruptures.

This is especially true in films that grapple with memory loss, where the fragility of recall becomes a metaphor for the instability of identity, the persistence of trauma, or the burden of history. Memory loss is more than a plot device, it is a philosophical question, an emotional landscape, and a psychological condition that intersects deeply with questions of identity, trauma, and reinvention.

Indian cinema, with its rich regional diversity and layered cultural histories, has often utilised the motif of memory loss as a complex cinematic metaphor, as presence and absence, as a way of exploring not only personal disorientation but also broader cultural anxieties about modernity, temporality, and the precarious construction of the self.

This article undertakes a cross-regional, thematic study of memory loss in Indian cinema, arguing that it operates simultaneously as a narrative strategy, a psychological metaphor, and a socio-cultural commentary. By tracing the depiction of memory loss across various cinematic traditions and genres, the study will explore how Indian films use this motif to reflect on trauma, love, masculinity, care, and the ever-shifting construction of identity in a rapidly transforming society.

Amnesia and the Mystique of Identity

Amnesia in Indian cinema often takes on an aura of mystique, serving not only to complicate plots but to destabilise identity itself. In psychological thrillers and romantic dramas, memory loss functions as a metaphor for the fragmented self, buried truths, and the deep ambivalence between remembering and forgetting. These films interrogate the foundations of subjectivity: Is identity formed through memory, or can forgetting offer a kind of liberation? The films discussed below transform memory loss into a narrative and philosophical puzzle that serves as a deeper inquiry about the human psyche and its vulnerabilities.

In “Moondram Pirai” (1982) and its Hindi remake, “Sadma” (1983), director Balu Mahendra portrays a woman who regresses to a childlike mental state following an accident. Viji (Sridevi), diagnosed with retrograde amnesia, is rescued from a brothel and cared for by a schoolteacher, Cheenu (Kamal Haasan), who grows emotionally attached to her. However, when she regains her memory in the final act, she forgets him completely.

The film’s devastating finale underscores the idea that memory constructs relational identity, who we are in the eyes of another. The caregiver’s anguish in the final scene becomes a testimony to love that was real but now unacknowledged, calling into question the very nature of emotional truth. Memory loss here becomes a site of ontological loss, severing not only connection but recognition itself.

Padmarajan’s “Innale” (1990) treats memory loss with lyrical ambiguity. Gauri (Shobhana), the protagonist, wakes up in a hospital after a traumatic incident with no recollection of herself and her past life. She adopts a new identity, Maya, and begins a life of emotional and psychological renewal. When her former husband discovers her, she no longer recognises him. Rather than romanticise reunion, the film meditates on the ethics of memory and identity: Does she have the right to remain in her new, peaceful identity, or is she obliged to return to her forgotten past? Is forgetting an act of self-care or denial? Is forgetting a blessing or betrayal?

Padmarajan leaves these questions unresolved, emphasising the emotional complexity of amnesia as both a coping mechanism and a silent rebellion. In this framework, memory becomes a contested site of personhood, its absence a radical redefinition of the self. Much like “Innale,” in Nikkhil Advani’s “Salaam-e-Ishq” (2007), Stephanie (Vidya Balan) loses all recollection of her relationship with Raju (John Abraham).

Raju decides to help Stephanie remember-or at least feel what they once shared. Stephanie’s amnesia is both a rupture and a reset, allowing the narrative to explore love not as a fixed recollection but as a process of rediscovery. Raju’s refusal to give up on her despite her forgetfulness transforms amnesia into a space of emotional resilience rather than erasure.

In Rosshan Andrrews’ “Mumbai Police” (2013), the protagonist ACP Antony Moses (Prithviraj Sukumaran) suffers from retrograde amnesia after a near-fatal accident. As he retraces his final days to solve the murder of a close friend, Aaryan (Jayasurya), he discovers a repressed aspect of his identity, his homosexuality, and, ultimately, that he is the murderer he seeks.

The film uses memory loss not simply as a mystery trope, but as a profound metaphor for psychological repression. Antony’s fragmented memory mirrors a fragmented self, torn between professional duty, masculine expectations, and a hidden emotional life. His amnesia becomes both literal and symbolic, a suppression of identity that reflects internalised shame and societal stigma. The film’s climax confronts the audience with a chilling paradox: that self-discovery can lead to self-destruction.

Beyond the Azure: Re-watching Ang Lee’s ‘Life of Pi’ Through a Decade of Discovery

In Diya Annapurna Ghosh’s “Bob Biswas” (2021), the spin-off from Sujoy Ghosh’s “Kahaani” (2012), memory loss functions as both a narrative reset and a moral conundrum. Bob (Abhishek Bachchan), a former assassin who awakens from a prolonged coma with no recollection of his violent past, is thrust back into a world that expects him to resume his role as an assassin. The film complicates the familiar trope of the amnesiac antihero by framing memory as both curse and absolution.

Is Bob still culpable for acts he no longer remembers, or does forgetting offer him a chance at moral rebirth? His internal struggle, between inherited identity and newfound conscience, mirrors the larger philosophical struggle about the self: if identity is rooted in memory, what becomes of ethics when memory is erased? As Bob teeters between submission to the criminal underworld and efforts to reclaim a life of normalcy, the film portrays amnesia not as emptiness but as a battleground where multiple selves contend.

In Amal Neerad’s “Bougainvillea” (2024), adapted from Lajo Jose’s novel “Ruthinte Lokam,” memory loss is not only a personal affliction but also a symbolic fracture in identity and reality. The protagonist, Reethu (Jyothirmayi), suffers from retrograde and anterograde amnesia, stemming from a car accident eight years earlier, leaving her caught between a constructed present and a buried past.

She juggles two temporalities, one structured by recorded reminders and daily routine, and another buried in traumatic memory. The film builds a slow-burning psychological thriller where the mystique of identity is sustained through missing time, hallucinations, and the symbolic recurrence of bougainvillea flowers and unfinished paintings.

Reethu’s journey to recover her lost self is rendered as an unravelling of both inner and outer worlds, where memory is at once a threat and a key to survival. As she uncovers the truth behind a series of disappearances, the film frames memory not as an archive of facts but as a volatile terrain of suppressed trauma, haunted subjectivity, and partial truths. In “Bougainvillea,” amnesia functions as a veil through which identity must be reconstituted, reminding us that remembering is neither linear nor safe, but a process of confrontation and reassembly.

Memory, Masculinity, and Violence

Memory loss in Indian cinema frequently intersects with themes of masculinity and violence, often revealing how psychological trauma both disrupts and reconstructs dominant notions of the male self. In some films, amnesia leads to the emergence of a violent masculine identity, a hypermasculine figure forged in the absence of emotional restraint or moral accountability. These narratives portray memory loss as a catalyst that liberates repressed aggression and righteous fury, often in response to societal failure or personal loss.

Conversely, some narratives depict memory loss as a rupture in violent masculinity itself, a disruption that allows the character to question, resist, or escape entrenched roles of aggression and control. In both cases, the forgotten past, marked by trauma, violence, or guilt, functions as a narrative pressure point that brings the male psyche into crisis. Whether reinforcing or destabilising masculine identity, these cinematic portrayals expose the fragility of the masculine ideal and its deep entanglement with memory, power, and pain.

In A.R. Murugadoss’s “Ghajini” (2005), memory loss becomes masculinised—a weaponised condition that fuels vengeance. While adapted from “Memento” (2000), “Ghajini” turns memory into action, the fragmented memory isn’t a passive loss but a trigger for obsessive violence. Sanjay Ramaswamy (Suriya) suffers from anterograde amnesia following a traumatic brain injury during a violent attack that also results in his lover’s murder.

He maintains a system of tattoos and Polaroids to track his revenge mission, his identity now reduced to the singular goal of violent retribution. The film presents a fractured masculinity held together by vengeance and rage, where memory loss paradoxically preserves trauma while erasing context. Sanjay becomes a figure of tragic hypermasculinity, his body marked, his mind broken, his emotions frozen in an endless loop of violence.

In Shankar’s “Anniyan” (2005), memory loss is intricately entwined with the splintering of masculine identity in a morally broken society. The protagonist, Ramanujam “Ambi” Parthsarthy (Vikram), is a meek, law-abiding citizen whose suppressed rage against systemic corruption gives rise to dissociative identity disorder, manifesting in two alternate personas: the stylish Remo and the brutal vigilante Anniyan. These identities, unknown to his conscious self, act out desires and frustrations he cannot openly express. His amnesia is not biological but psychological, selective and defensive, enabling a compartmentalisation of guilt, desire, and justice.

The film stages this dissociation as a direct response to the failure of moral idealism and the emasculation of the ethical man in a society governed by injustice. Anniyan’s violent excesses become the shadow of a repressed masculinity, which cannot reconcile vulnerability with righteous rage. Memory here is a metaphorical battleground, where forgetting allows survival, but at the cost of a unified self. Shankar renders the fractured mind as spectacle, while also critiquing the dangerous thresholds at which masculinity, memory, and morality implode.

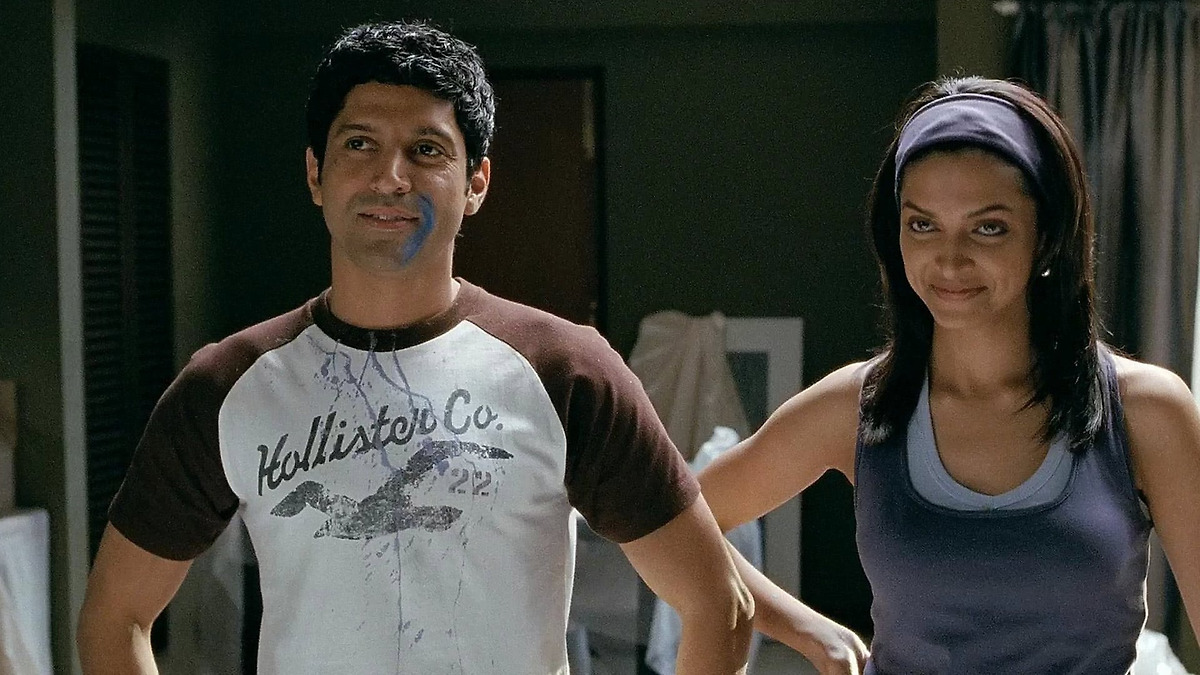

In “Karthik Calling Karthik” (2010), directed by Vijay Lalwani, memory loss and dissociation are tied to a crisis of masculinity in an urban, high-pressure professional setting. Karthik is portrayed as a timid and ineffectual man, repeatedly undermined at work and in his personal life. The mysterious phone calls from “another” Karthik, later revealed to be manifestations of his dissociative identity disorder, awaken a more assertive, dominant version of himself. This internal split signals a deep psychological fracture, where memory lapses allow the emergence of a hypermasculine alter ego capable of ambition, confidence, and aggression.

How the 2019 Malayalam film Ishq showed a middle finger to toxic masculinity

The film uses memory dysfunction to dramatise how the pressures of modern masculinity can create inner dissonance, where the need to succeed and be seen as ‘man enough’ leads to a psychological rupture. The narrative arc thus oscillates between empowerment and self-destruction, exposing the volatility of masculinity constructed on repression and unresolved trauma.

Revisited here under a different lens, ACP Antony Moses’s memory loss in Rosshan Andrrews’ “Mumbai Police” (2013) not only catalyses the narrative but also exposes the instability of masculine performance. As he uncovers his own culpability in a murder and confronts his repressed queer identity, his amnesia serves to interrogate the moral absolutism often attached to male law enforcers. Memory becomes the site of internalised violence, both inflicted and received – sexual, psychological, institutional.

Similarly, in “Bob Biswas” (2021), Bob’s amnesia distances him from the violence of his past, allowing a momentary reprieve from the burden of masculine aggression. Yet as he is drawn back into the role of assassin, the tension between the person he was and the man he might become reveals how masculinity in Indian cinema is often defined by one’s capacity to enact or resist violence. Memory recovery becomes a tragic reinstatement of this violent legacy. In both narratives, amnesia becomes a suspenseful mirror: What if your own memory holds the key to your darkest acts?

Remembering the Unremembered: Alzheimer’s, Dementia, and the Ethics of Care

Indian cinema has, in recent years, taken a more compassionate turn in portraying memory loss not as a plot twist or narrative mystery, but as a lived condition, especially in films that depict Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. These portrayals move beyond the metaphorical and toward the phenomenological, focusing on the slow, painful erosion of memory and its impact on family, care, and identity. In these films, memory loss becomes an intimate site of ethical negotiation, of how one loves, tends to, and ultimately makes peace with a vanishing self.

Blessy’s “Thanmathra” (2005) remains one of the most sensitive portrayals of Alzheimer’s in Indian cinema. The protagonist, Ramesan Nair (Mohanlal), a disciplined government officer and devoted father, begins to lose his memory. What starts as commonplace omissions and absentmindedness quickly grows into handicapping cognitive and behavioural impairments. The film focuses less on the spectacle of disease and more on its emotional, domestic, and social consequences.

The film navigates how memory anchors familial roles and identity, as Ramesan forgets his son, his home, and eventually himself, the film renders this cognitive erosion as a form of slow, lived trauma. It is also a trauma for the family, particularly the son, who must witness the fading of a once-stable figure. The film critiques the fragility of middle-class aspirations and familial bonds when confronted with irreversible mental decline. The protagonist’s descent into forgetfulness becomes a metaphor for the unmaking of middle-class aspirations, fatherhood, and individuality.

In films such as “Thanmathra” (2005) and Ratheesh Balakrishnan Poduval’s “Android Kunjappan Ver 5.25” (2019), memory loss is linked to ageing and neurodegenerative illness, becoming a slow, tragic erosion of self. In “Thanmathra,” the protagonist’s descent into Alzheimer’s disease is not merely medical, it is existential.

His identity as a father, government employee, and dreamer is dismantled piece by piece, challenging the viewer to confront the social and emotional toll of forgotten lives. Similarly, in “Android Kunjappan Ver 5.25,” the father-son relationship is mediated through a robot, yet haunted by the gradual fading of human memory, drawing attention to the ethical crisis of replacing caregiving with machinery in an ageing society.

In “Astu” (2013), directed by Sumitra Bhave and Sunil Sukthankar, memory loss is portrayed with philosophical subtlety. The story follows Dr. Chakrapani Shastri, a Sanskrit scholar suffering from Alzheimer’s, who wanders off with a street elephant and her caretaker. The juxtaposition of ancient wisdom and fading memory becomes a poetic inquiry into what constitutes identity, knowledge, relationships, or the continuity of consciousness.

His daughter’s frantic search is intercut with meditative scenes of his gentle dissociation from linear time. Rather than framing Alzheimer’s as loss alone, “Astu” explores the metaphysical dimensions of forgetting, treating memory not only as data but as presence, ritual, and embodiment.

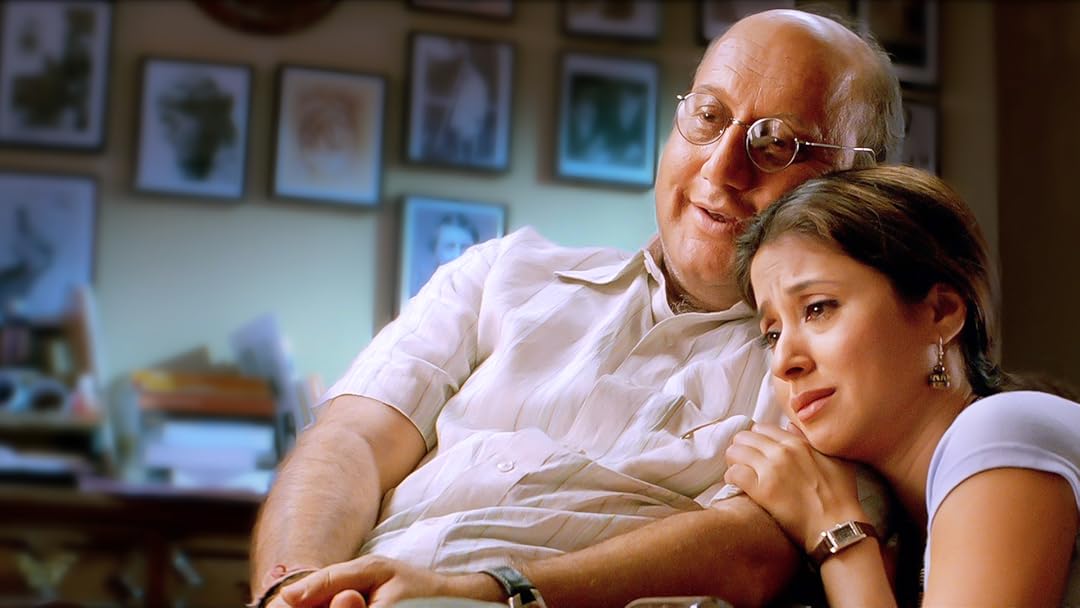

Jahnu Barua’s “Maine Gandhi Ko Nahin Mara” (2005) centres on a retired professor, Uttam Chaudhary (Anupam Kher), who develops dementia and begins to believe he is accused of assassinating Mahatma Gandhi. The film uses this delusion as a psychological metaphor for collective guilt, historical amnesia, and national trauma. It blends personal decline with political allegory, suggesting that memory loss, whether individual or cultural—has profound ethical implications. His daughter’s efforts to care for him double as an act of witnessing, reminding us that dementia tests not only the mind but also the moral capacity of those who remain.

Hemanth Rao’s Kannada film “Godhi Banna Sadharana Mykattu” (2016) deftly blends social critique with emotional depth. Venkob Rao, an old man with Alzheimer’s, goes missing, setting off a parallel search by his estranged son. The film oscillates between Venkob’s disoriented wanderings and his son’s slow awakening to the emotional neglect that preceded the illness.

The father’s fragmented memories, rendered through minimal flashbacks and poignant dialogues, reveal not only cognitive decay but also emotional truths long buried. “Godhi Banna Sadharana Mykattu” suggests that Alzheimer’s does not erase the emotional self; it amplifies what remains unsaid. In reconciling with his father’s condition, the son also reconnects with his own emotional inheritance.

10 Great Movies from Bad Directors You Must Check Out

These films challenge dominant cinematic representations of memory as heroic recall or suspenseful absence. Instead, they present memory loss as a gradual undoing that is both profoundly human and relational. In portraying Alzheimer’s and dementia, Indian cinema begins to engage with the ethics of care, the temporality of decline, and the dignity of those who forget, and those who remember.

Soft Amnesia: Nostalgia, Love, and the Selective Past

While many Indian films focus on the drama of memory loss through amnesia or psychological trauma, another equally evocative theme is that of emotional forgetting, often framed through nostalgia, selective memory, and acts of willful erasure. Unlike pathological forgetting, emotional forgetting in cinema often emerges from a desire to move on, to cope, or to preserve an idealised version of the past. This kind of memory work is subtle, melancholic, and deeply relational, entangled with the politics of longing, regret, and identity.

Cheran’s “Autograph” (2004) is a meditative journey through memory, where nostalgia becomes both a narrative form and an emotional device. As the protagonist Senthil (Cheran) retraces his past to invite former lovers and friends to his wedding, each encounter becomes an occasion for emotional reckoning rather than mere reminiscence.

The film does not centre on pathological amnesia, but on emotional forgetting, how people selectively hold onto or suppress experiences to make peace with themselves. Through a series of vignettes, “Autograph” evokes memory not as fixed history but as personal myth, reshaped by time, regret, and reconciliation. Emotional forgetting here is not a failure of memory but a coping mechanism, allowing the protagonist to move forward while carrying the spectral presence of what was once loved and lost.

Anvar Sadik’s “Ormayundo Ee Mukham” (2014) offers a lighter, romantic take on memory loss, yet it touches upon deeply emotional undercurrents about identity, love, and time. Inspired by “50 First Dates,” the film follows Nithya (Namitha Pramod), a woman with short-term memory loss who forgets each day anew after a traumatic accident. While the premise may seem whimsical, the film navigates the repetitive labour of love, where her love interest, Gautham (Vineeth Sreenivasan), must win her over afresh each day.

Memory here becomes not only a condition but a daily test of commitment and emotional presence. Rather than depicting amnesia as rupture or mystique, the film treats it as a lived rhythm, one that challenges linear notions of intimacy. The visual motifs of diaries, recurring events, and soft montages create a loop of affection and familiarity, suggesting that even in forgetting, emotional connection can endure. The film’s tenderness lies in its insistence that love, when genuine, adapts to the erasures of memory without demanding restoration.

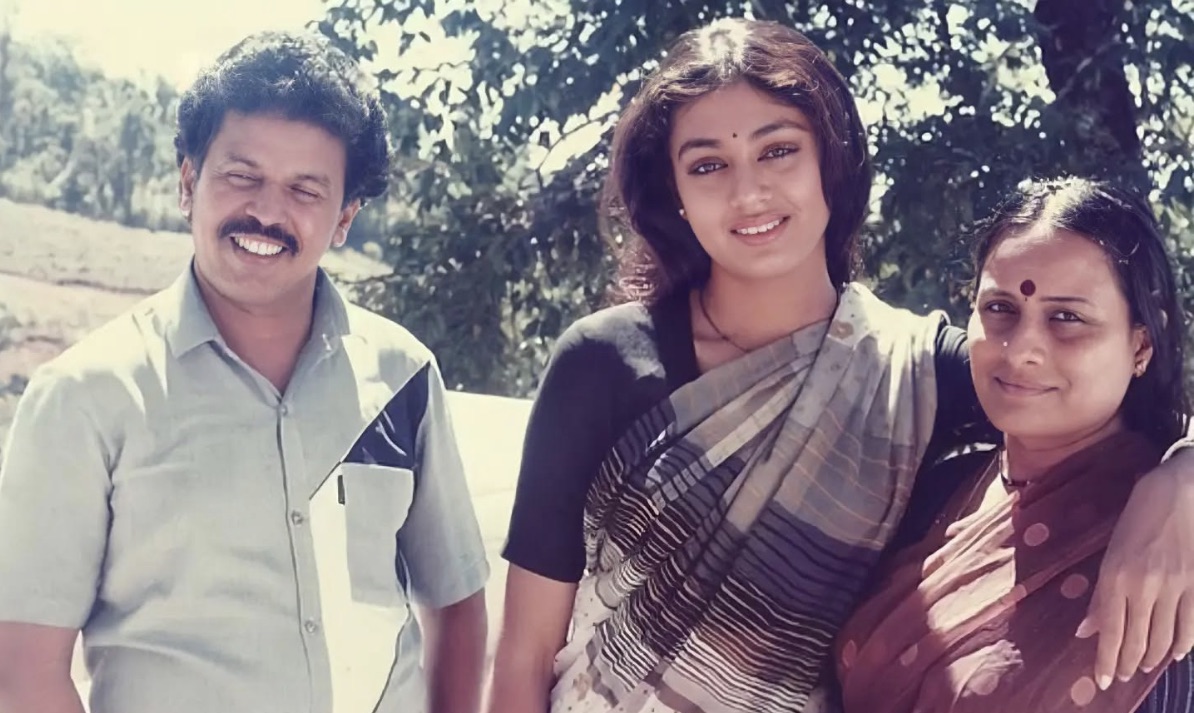

In Alphonse Puthren’s “Premam” (2015), memory is shaped not by loss but by selective recollection. George’s (Nivin Pauly) evolution from teenage infatuation to adult emotional maturity is marked by three key romantic relationships, each fading into the past yet shaping his future self. The most striking use of memory occurs during his relationship with Malar (Sai Pallavi), who suffers temporary memory loss after an accident.

But she eventually regains it, only to end up marrying someone else. The film’s structure, episodic, nostalgic, and tinged with bittersweet recollection, reveals how emotional forgetting is less about erasure and more about transformation. The past isn’t denied; it is mourned, refigured, and finally integrated into a more grounded masculinity. Nostalgia, here, is not indulgence but a quiet reckoning with what cannot be reclaimed.

Padmarajan’s “Innale” (1990) can be reread here as a meditation on emotional forgetting. Gauri’s refusal or inability to return to her former life and her husband can be seen as a subconscious choice to protect her reconfigured self. The past becomes an emotional burden she sheds, not out of malice but necessity. The film subtly suggests that forgetting is not always involuntary, it can be a psychological strategy, a quiet resistance against being reabsorbed into a painful past. The film renders forgetting as a tender, if painful, act of self-preservation.

Rojin Thomas’s “Home” (2021) explores memory not as neurological loss but as emotional erosion, forgetting shaped by generational disconnect, technological alienation, and changing cultural values. Oliver Twist (Indrans), the ageing father, doesn’t suffer from dementia but from the subtler disintegration of relational memory: his relevance and emotional presence are gradually erased by his sons’ busy lives and digital distractions. His awkwardness with smartphones reflects a deeper dislocation, his inability to “sync” with a world that no longer values slowness, attentiveness, or vulnerability.

Oliver’s quiet, persistent attempts to reconnect position him as a living archive of familial care, whose memories, neither dramatic nor traumatic, are overwritten by everyday indifference. “Home” treats memory as operating on two registers: as the father’s internal reservoir of affection and as the family’s collective forgetting of what he represents. It reframes amnesia as emotional and cultural rather than medical, showing that the most painful forgetting happens not in the mind, but in the heart.

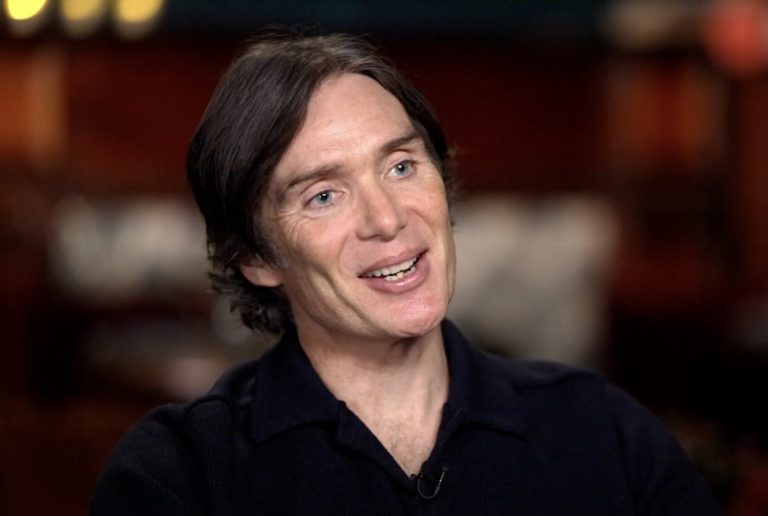

Avinash Arun’s “Three of Us” (2023) is an introspective portrayal of early-onset dementia, tracing its emotional and relational contours. The film follows Shailaja (Shefali Shah), a middle-aged woman who, upon being diagnosed with a degenerative neurological condition, embarks on a quiet journey to her childhood town in coastal Maharashtra. Rather than focus on medical symptoms or narrative suspense, the film meditates on memory as affect, fragile, buried, and often bittersweet.

Of Remembrances: ‘Three of Us’ Is A Poetic Ode to Memories

Shailaja’s return to places and people from her past, including a long-lost friend and former crush, Pradeep (Jaideep Ahlawat), becomes a reclamation of moments left unresolved. The film portrays dementia not as a loss of self but as a slow reorientation, an invitation to reconnect with unspoken emotions and lingering questions. In “Three of Us,” memory loss becomes a conduit for emotional clarity, transforming the narrative into a quiet elegy for time, love, and the fading contours of identity.

Memory as Trauma: The Unbearable Weight of the Past

In Indian cinema, memory loss is frequently used to depict trauma that is too overwhelming for the psyche to process. The forgetting, in these cases, is less a malfunction than a psychological defense mechanism, a form of emotional survival in the face of deeply distressing events such as grief, violence, or emotional shock. In such films, the rupture of memory reflects a rupture in the psyche.

In Rahi Anil Barve’s “Tumbbad” (2018), trauma is less psychological than mythic and intergenerational, embedded in the landscape and inherited through bloodlines. The film’s protagonist, Vinayak (Sohum Shah), is haunted not by a single violent event but by the legacy of greed and ancestral sin, symbolised by the forbidden deity Hastar. Memory here operates not through individual recall but through cultural repression: the villagers’ silence about the goddess, the hidden chamber, and the rituals of secrecy all constitute a collective act of forgetting.

Yet the trauma of this erasure returns cyclically, manifesting in bodily decay, familial breakdown, and existential ruin. The film treats memory as a suppressed curse—what is locked away in the womb must eventually resurface. “Tumbbad” transforms trauma into a gothic allegory, showing how the refusal to reckon with the past – whether historical, mythological, or ethical – leads to perpetual repetition. Memory is not narrated, but embodied in the decaying architecture, the stormy landscapes, and the protagonist’s descent into obsession. In this sense, trauma is both literal and symbolic: a hunger that consumes everything, including the self.

Dinjith Ayyathan’s “Kishkindha Kaandam” (2024) reframes the narrative of memory loss as a cyclical encounter with trauma, rather than a mere neurological condition. At the heart of the film is Appu Pillai (Vijayaraghavan), a retired army officer suffering from undiagnosed amnesia, whose deteriorating memory is not only an affliction of the mind but also a symptom of repressed guilt, unresolved grief, and the haunting legacy of violence within a fractured family structure.

The film draws on the metaphor of the “investigator haunted by his own findings,” as Appu Pillai unknowingly pieces together and then destroys the truth of his grandson Chachu’s tragic death in a repetitive loop. His amnesia, rather than being a total void, manifests as trauma-induced selective memory: a mind that can remember just enough to investigate, but not enough to fully process or survive the implications of that knowledge.

Memory becomes an unconscious act of protection and self-censorship, as Appu Pillai repeatedly rediscovers that his licensed pistol was involved in the death of his grandson, only to forget and suppress the truth once again. Ajayan (Asif Ali), the son, acts as both caretaker and accomplice, navigating the impossible moral terrain of protecting his father’s dignity while sustaining a deeply painful secret. The trauma is distributed across generations, with each character bearing the weight of memory differently: Appu Pillai forgets, Ajayan remembers but suppresses, and Aparna (Aparna Balamurali), the outsider-wife, becomes the reluctant catalyst who uncovers the family’s suppressed horror.

Comic Amnesia: The Funny Side of Forgettting

Memory loss as a comic device in Indian cinema often operates in contrast to its more serious and dramatic portrayals, turning a typically tragic or unsettling theme into a source of humour and light-heartedness. In these films, memory loss is used as a mechanism to generate confusion, mistaken identities, situational absurdities, and emotional missteps, all of which serve to entertain and create comic tension. The exploration of memory loss within a comedic framework highlights how this motif, though rooted in vulnerability and disorientation, can also offer moments of levity and social critique.

“Ek Ladka Ek Ladki” (1992), directed by Vijay Sadanah, exemplifies the use of amnesia as a comic and romantic device, aligning with the screwball tradition of mistaken identity and farcical entanglements. The film follows Renu (Neelam), a wealthy heiress who loses her memory after a car accident and ends up in the care of Raja (Salman Khan), a carefree, lower-class man who deceives her into believing she is his wife. The humour in the film arises from the incongruity between Renu’s real aristocratic background and her new modest lifestyle, played for comic and romantic tension.

Memory loss here functions not as a psychological condition but as a plot convenience that enables role reversal, gendered humour, and class critique, albeit in a light-hearted tone. When memory is eventually restored, the comic illusion collapses, but love prevails. The film reframes amnesia not as trauma, but as temporary liberation and a whimsical detour from social hierarchies and rigid identity roles.

Cinema as a Path to Transformation: The Power of Film to Shape Identity

In Rajkumar Santoshi’s “Andaz Apna Apna” (1994), memory loss is spoofed with brilliant irreverence. Aamir Khan’s character Amar pretends to suffer from amnesia (as “Tillu”) to con his way into a wealthy heiress’s affections. This feigned amnesia spirals into a wildly absurd sequence where Salman Khan’s character plays along as a doctor. The trope is purposefully exaggerated to highlight how easily serious conditions like memory loss can be manipulated in mainstream narratives for personal (and comic) gain.

In Priyadarshan’s “Kilukkam” (1991), memory loss is framed within a larger comedic narrative, but unlike “Andaz Apna Apna,” it carries undertones of vulnerability and misunderstanding. Revathi’s Nandini has a mental illness that leads to memory loss and erratic behaviour. She arrives in Ooty as a tourist and is taken in by Joji (Mohanlal), a tourist guide, who later discovers she is an escaped mental patient with a bounty on her return.

The movie explores the comedic situations arising from Joji’s attempts to get rid of her and the eventual realisation that she is in danger from her relatives. Her memory loss, or more precisely, her erratic mental state, is not played for ridicule directly, but rather fuels a cascade of comic confusion and situational comedy.

Balaji Tharaneetharan’s “Naduvula Konjam Pakkatha Kaanom” (2012) offers a comedic yet strikingly realistic portrayal of temporary memory loss, rooted in an actual incident from the director’s own life. The protagonist, Prem, suffers from anterograde amnesia after a head injury just days before his wedding.

What unfolds is a delicate balancing act between humour and anxiety, as Prem repeatedly forgets the immediate past, unable to retain new information beyond a few minutes. The film’s minimalistic setting and repetitive dialogue structure cleverly simulate the claustrophobic loop of short-term memory loss, creating both comic absurdity and emotional tension. The friends’ efforts to shield Prem’s condition from his fiancée and family serve as both farce and testimony to the fragility of identity when memory is compromised.

Memory in Indian cinema is a richly layered palimpsest, continually overwritten by personal trauma, cultural myth, romantic longing, and political anxiety. From the mystique of amnesia in psychological thrillers to the emotional forgetting of nostalgic romances, from the violent ruptures of masculine identity to the quiet unravelling of dementia, memory loss has served as both a narrative engine and a philosophical inquiry into what it means to remember, to forget, and to become.

These films reveal that memory is not merely a function of cognition, but a complex emotional and ethical terrain. Whether lost suddenly, erased deliberately, or disintegrated slowly over time, its cinematic portrayal becomes a meditation on identity, intimacy, and the instability of the self. In the act of remembering and forgetting, cinema captures not just the mind’s fallibility but the heart’s resilience, offering stories where memory is not only a plot device but a reflection of the human condition itself.

![[WATCH] Video Essay Explores How Christopher Nolan Manipulates Time](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Christopher-Nolan-768x332.png)