Movies like The Killer on Netflix: Streaming on Netflix after a limited release in theatres, “The Killer” is David Fincher’s return to the genre of crime and thriller, which he had managed to hone and perfect by the late 90s and early 2000s. Clearly a style statement, “The Killer” is nonetheless distinctively Fincher-ian, and it also shares its DNA with lots of other movies within the same umbrella of crime and thriller space. It is such a vast umbrella that a list like this could run the risk of being too broad. Thus, the movies selected are done through a specific lens of tone, filmmaking style, as well as the genre they are referencing or inspired by. I am sure I am missing a lot, so please put your list down in the comments section, and let’s start a conversation.

7. The House that Jack Built (2018)

On the surface, “The Killer” and “The House that Jack Built” couldn’t be more different. “The Killer” is about a ruthless assassin, while “The House that Jack Built” is about a serial killer reminiscing about five murders and interspersing them with his own rationalizations tinged with intellectualism. From a filmmaking standpoint too, both these movies share distinctly different and yet unique, overwhelming directorial voices all on their own, and yet this exact difference is what puts this film on the list.

“The Killer” is about a distraught assassin trying his hardest to maintain order and control over each and every aspect of his assignment, down to the preciseness of his heartbeat to shoot. In a way, “The Killer” is Fincer’s most biographical film, where he uses a genre template to create an autofictional narrative about a man who is not averse to putting a mirror on himself and acknowledging it with a sense of sheepishness.

“The House that Jack Built” is Lars Von Trier’s attempt at autofiction through a similar genre template that invites provocation in exploration of Von Trier’s own begrudging themes, which get called back and oft-repeated, but there is also a sense of artistic frustration that wouldn’t be out of the ordinary. Second-hand voiceover via conversation with Virgil also takes the genre element of the neo-noir template both this and “The Killer” are trying to emulate, and of course, there is a dark sense of humor throughout the narrative, even if both of the directorial voices are so vastly different.

6. Haywire (2011)

In a vacuum, David Fincher isn’t the only celebrated auteur to take a crack at what one would mostly call “trashy genre fare,” like a movie about contract killers and assassins. Fincher’s style permeates through every frame of “The Killer” to the extent that the movie could be called an elevated stylistic exercise with a special focus on formalism and ruthless efficiency in filmmaking. A similar commentary could be presented in Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 outing “Haywire.”

There is efficiency in every frame of Haywire, which follows Mallory Kane (Gina Carano), a black ops agent betrayed by her employers and targeted for assassination. There are issues with Carano’s dubbing, but not any issues with the action sequences, which the movie devotes most of its time to. Soderbergh revels in his editing, his choice to keep the movie as exposition-light as possible, and his sharp cuts, which are especially important for creating seamless movement within and between action set pieces.

But an apt comparison with “The Killer” would be a similarly strict and banal approach to the corporatization of even an organization like assassination or contract killing, where conflict and disconnect between bosses and employers could cause rustication. Except here, that usually means death until she proves herself useful and is offered a job back within the organization. “The Killer” chooses to view that with apathy; “Haywire” views that with nonchalance as more of a part of the narrative than a commentary.

5. The Mechanic (1972)

“The Killer” opens with a twenty-minute sequence where our unnamed protagonist stakes out a Parisian house from the opposite window of a WeWork, listening to the Smiths and commenting on the process of his job in his head while waiting for his target to appear until he misses. Michael Winner’s 1978 action thriller “The Mechanic” opens with a similar and yet exactingly different opening sequence—a full sixteen minutes where Charles Bronson’s Arthur Bishop prepares to execute his assignment—and the sequence features no dialogue.

Admittedly, that is different, and yet Winner wastes no time in showing Bishop’s expertise in his job of making the kills look like accidents and not foul play. Like Michael Fassbender’s unnamed protagonist, Bishop also works for a secret organization with its own strict rules. Like “The Killer,” “The Mechanic” is about a hitman running afoul of his higher-ups once he fails in his assignment and is targeted, and how he would have to go after them systematically. There are, of course, differences, like the presence of an apprentice, but even that causes conflict with the bishop and the organization that works for him.

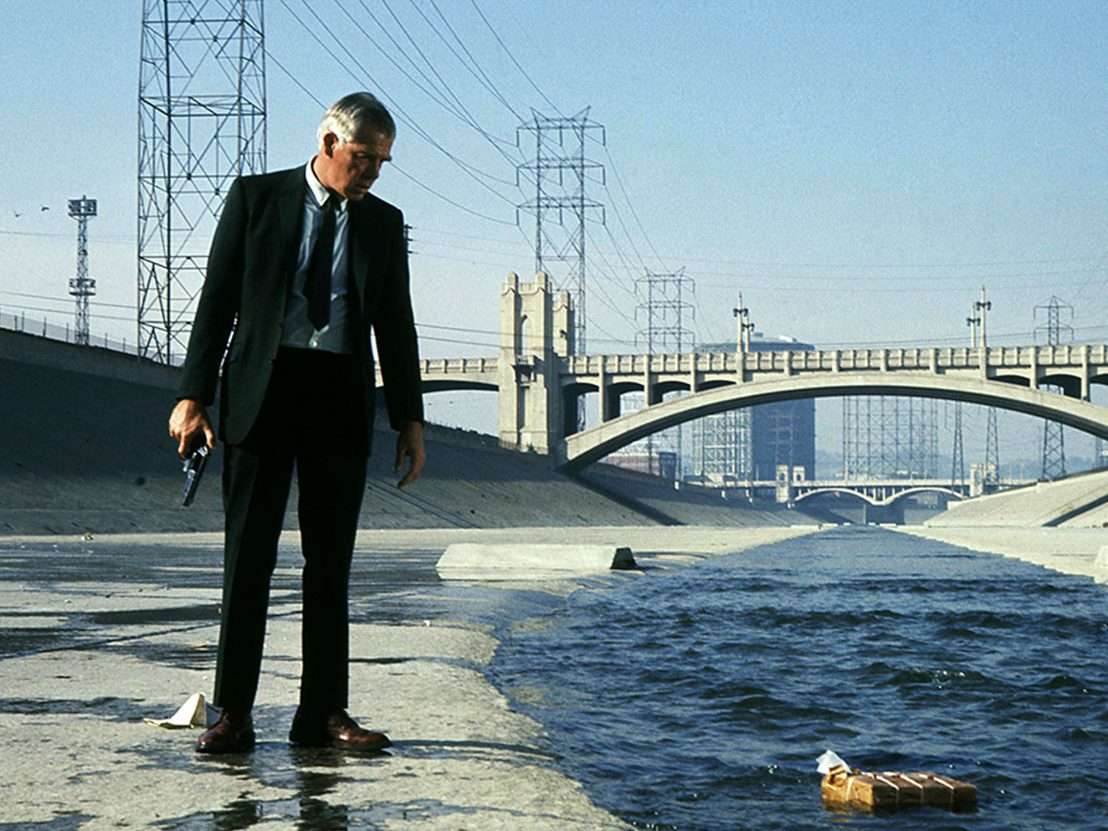

4. Point Blank (1967)

In most of these assassin movies, the assassin’s mettle is tested when they are attacked, either by the person or the ones closest to them, and the response is a seething journey of retribution through the hierarchy of the organizational ladder that has chosen to betray them. The hideout in the Dominican Republic being attacked is enough to elicit a response from Fassbennder’s titular “The Killer,” a similar response to the criminal Walker in John Boorman’s 1967 classic “Point Blank.”

One could call “Point Blank” a revenge flick, and that wouldn’t be the wrong genre to slot the film into. However, there are elements in this that manage to ensure the movie slips in and out of the slot. For one thing, it is a killer working against an “organization,” and the killer’s code is almost stubbornly simple: he wants his $93,000 back. It’s again a systematic way to move through the levels of an organization and the ladders to ultimately reach the end of a money trail. But, unlike Fassbender’s protagonist in Fincher’s film, Lee Marvin’s Walker extracts almost a pitiless form of violence.

There is also a strong sense of style in framing, editing, and unique use of sound mixing to disorient the audience, similar to how “The Killer” shifts from diegetic to non-diegetic music to shift focus. With subversive music and stylistic escapades, and a focus on the intermixing of brightly colored fluids at a kitchen sink to emulate the sense of dream logic, “Point Blank” is one of the early few films trying to elevate the “B-movie trashy genre template” into an arthouse action setpiece of elevated nature.

3. Blast of Silence (1961)

Some might call “The Killer” a high-end B-feature, which would be talking down to the catharsis one experiences while watching a low-budget genre film. But Allen Baron’s low-budget 1961 shlocky feature “Blast of Silence” is the one film that eschews the closeness to Fincher’s own style in “The Killer.” Following a hitman working for the Cleveland Mafia as he traverses through New York City for a week to complete an assignment, Baron’s film could be called comical if the voiceover is any indication.

Unlike “The Killer,” where Fassbender drones with a first-person voiceover, talking about the ethics and codes of the hitman while in reality completely failing at each and every turn, the voiceover in “Blast of Silence” is in second-person and with the sharpness of a buzzsaw, the quintessential hard-boiled drawl. It seems to hold up an internal mirror for Frankie Bono’s damaged psychology, almost acting as a defense mechanism. There is a black sense of humor within its hardened bite, which “The Killer” emulates. But there is also a focus on showcasing New York with a gritty, documentary-like style, particularly during the procedure of attaching a silencer to a gun or a fight with a heavy-set individual ending in a bloodbath.

2. Murder by Contract (1958)

One could sense while watching “The Killer” that our unnamed protagonist has the cynicism of a man almost stuck in a dead-end job in the gig economy. The fact that the job is about killing is beside the point because, according to the man, the monotony could only be helped by a lack of empathy, as he re-affirms the tenets of his work while trying to execute his assignment. Irving Lerner’s 1958 noir “Murder by Contract” is one of these earliest noirs, with its spare filmmaking style, a peculiar sense of nonchalance, and a hitman grappling with existentialism.

Considering the fact that Claude joins the organization as a “contractor” to pay off the down payment on a house, the humor is very much a laconic and dark one, with Claude’s set of skills coming into sharp contrast with his set of twisted tendencies that get in the way, especially his weird hang-up about the final client being a woman because “women are unpredictable.” Much of the film also deals with Claude’s own methodology of training, his self-inflicted wounds, and the procedural-oriented nature of murder, which has come to inspire multiple movies of this genre, including “The Killer.” And, of course, the caustic and hilarious black humor-tinged voiceover is eager to cite details and affirmation of existentialism.

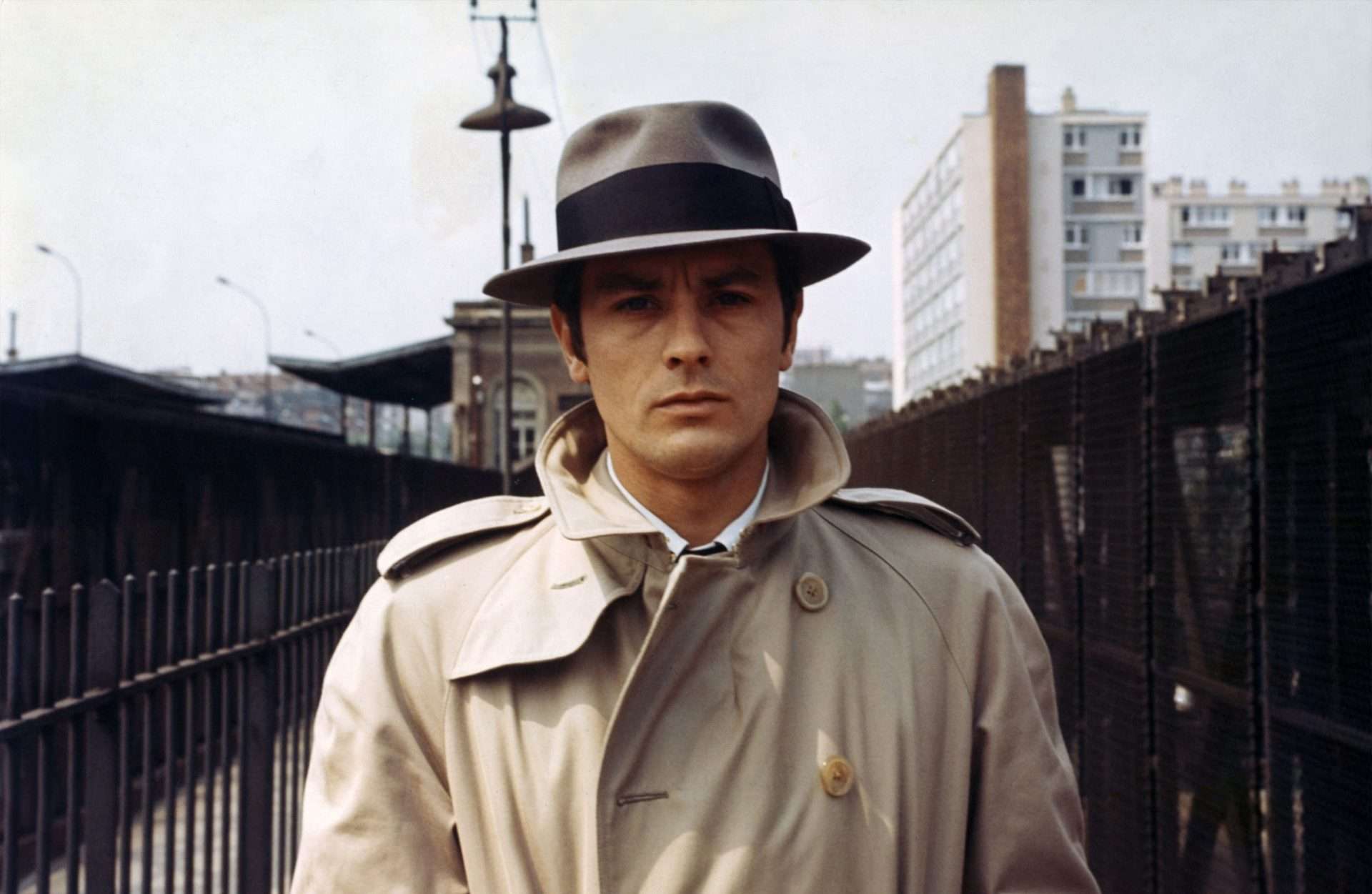

1. Le Samourai (1967)

To make a hitman film embellished with the procedural nature while achieving precise formal style, look no further than Jean Pierre Melville’s 1967 neo-noir “Le Samourai.” “Le Samourai” follows a professional hitman, Jef Costello (Alain Delon), trying to find someone who would want to have him killed after hiring him for a job, while a wily Parisian commissaire tries to catch him.

As Fincher himself admitted in an interview, you can’t make a movie like “The Killer” without referencing “Le Samourai” in some form or fashion. “The Killer” moves like a homage to Melville’s masterpiece while also deliberately commenting on elements of Melville’s visual aesthetic. If Le Samourai had Costello use a bunch of keys to identify and hotwire a car, “The Killer” has the unnamed protagonist use a key fob.

While Costello’s own get-up resembles the typical film noir protagonist, he is very much able to navigate within society and not draw attention—a similar ploy employed by Fassbender’s killer, but through his own laconic dress code, which is far from being beatific. Fincher’s own clean style, sharp edits, and focus on the details and incidentals are very much inspired by Melville meticulously following Costello in “Le Samourai,” but not entirely with the same amount of solipsism as Fincher’s latest.

![Call My Agent: Bollywood [2021] Netflix Review – A show about the lives of talent agents works when it is leaning into satirizing Bollywood](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Call-My-Agent-Bollywood-768x432.jpg)

![Berberian Sound Studio [2012]: Sound of Paranoia](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/215634-Berberian-Sound-Studio.jpg)