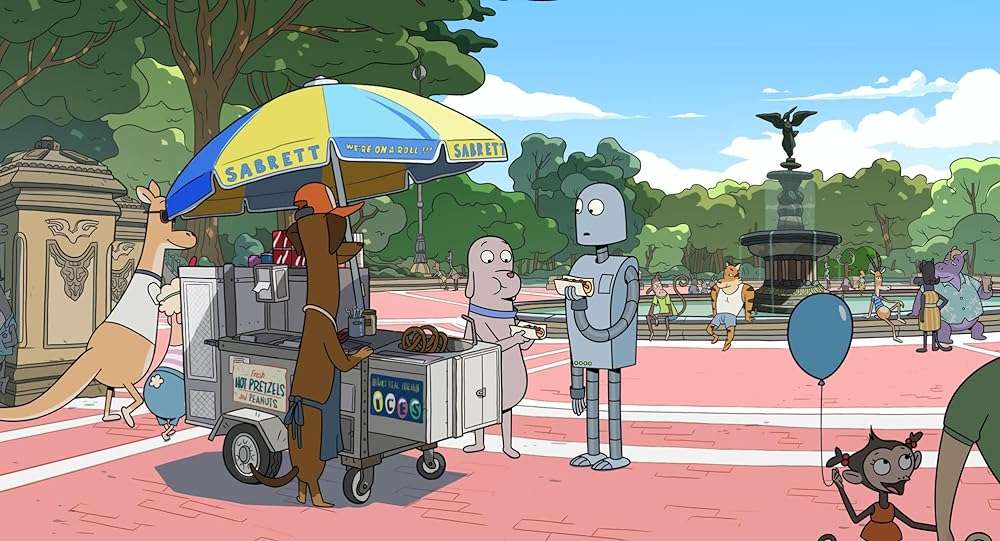

Pablo Berger’s “Robot Dreams” might be created via simple animation in terms of the details of the anthropomorphic characters, but it doesn’t lack detail within the environment the film is set in. The opening scene alone showcases Dog’s loneliness as he heats up Mac and Cheese for dinner and sits down on his sofa. Meanwhile, in the background, we see a couple (a giraffe and a hippo) sitting down in their apartment opposite to watch a sitcom to finish their dinner. This occurs before Dog notices the couple, feels a pang of loneliness, and then watches as the advertisement for a do-it-yourself robot flashes across his television. In a city resembling 1980s New York, Dog then creates his own companion resembling “The Iron Giant.”

Their friendship is an immediate spark, a match to a flame, as Robot’s curiosity about the world he wakes up to is complemented by Dog’s delight in finding a friend with whom he can share his interests. Until one day, on the beach (very clearly recalling Coney Island with its colorful beach umbrellas and the crowd of people, here denoted by a variety of anthropomorphic animals with markers like turbans or tattoos highlighting smaller details), Robot gets rusted due to bathing in the water for too long. Dog tries his hardest to pull him up from his prone position before leaving him there, adorned in a blanket. His troubles get compounded when he realizes that the beach will be closed until June 1st, and even his “best-laid plans” will all go for naught. Thus, both Dog and Robot would have to wait until the beach opens to be reunited.

The above paragraph comprises the first 29 minutes of the narrative, and it is sublimely paced, edited to the tracks of Earth, Wind, and Fire, and without the crutch of dialogues, the movie relies on the expressions of the characters. Those expressions are not hobbled by the simplicity of the designs of the characters. On the contrary, the evocations of those expressions are amplified due to their simplicity, automatically adding a sense of wholesomeness even within the inevitable despondency the movie dips its toes into. But after those minutes, the movie starts to lose its steam. It’s understandable what Berger is trying to show—the act of moving on by both an anthropomorphic individual as well as an individual made of robotic parts but possessing sentience.

“Robot Dreams” feels like Berger answering the question raised by Philip K. Dick, “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”. Perhaps not, but robots do dream. Their dreams range from imagining escaping the rusted prison by being fed a can of oil and then walking up to his owner’s house, only for his dreams to be shattered by a group of boy-scout ferrets breaking one of his legs, breaking off one of his toes, and using it to fill the hole in their rapidly sinking boat. In contrast, Dog is shown to go through a sense of detachment.

If Dog is the representation of humanity, his trying to enjoy himself by celebrating Halloween or the kite festival, meeting a new friend in the form of a Duck, or going sledding in the winter and hurting himself is his act of moving on. The myriad of new experiences grants Dog a freedom that Robot lacks, while forgetfulness via the passage of time helps heal the wound of the loss, or at least slightly mellow it down. In contrast, the Robot’s dreams become more surreal. In one of the best sequences of the movie, we see Robot having dug out of the snow right out of the frame of the movie.

He then pushes the frame, rotating it and revealing the canvas behind—a painting of a summer isle, almost like a sequence from “The Wizard of Oz.” But even within the surrealism that doesn’t break the form of animation, Robot’s dream is very much attached to Dog. But it’s that lingering echo of his friend that characterizes Robot as an individual who doesn’t lose either his memory or his innocence. That innocence begets empathy, which produces a heartwarming sequence between Robot and a bird’s hatchling.

All these events cumulatively develop the characters of Robot and Dog as the year progresses and New York, through the 80s, changes its looks through the seasons. But amidst all of that, the central point of the movie—the relationship between Dog and Robot—changes, and the plot starts becoming disengaged, especially in the middle. The vignette and episodic-based storytelling in that region is an excuse for Berger, animation director Elena Pomares, and creative partner Jose Luis Agreda to flex their animating and creative juices. Those vignettes become a tour of 80s New York through its different seasons through the eyes of the trio. It is a sight to behold, especially in the sheer amount of details smashed into every frame (the graffiti, the design of the grime of the metro stations, the spicy smoke ejected by forcefully opening a packet of Cheetos), but it also becomes very meandering.

There is a compelling argument, especially if one considers the final 20 minutes of the film, that “Robot Dreams” might have benefitted from being a short film or perhaps focusing only on the robot’s perspective (as the title states, “Robot Dreams”). But it is those final 20 minutes where the thesis statement of the movie becomes abundantly clear—the juxtaposition of the dream of reuniting, spurned by nostalgia, and yet the maturity to realize that it is better to move on and search for happiness amidst the circumstances of the present rather than wallowing in the past. It is “Past Lives” depicted via animation through the lens of Issac Asimov and Philip K. Dick, but with wholesomeness, aided by the score of Alfonso De Villalonga and the catchy tunes of Earth, Wind, and Fire.

![Victim [2022] ‘Venice’ Review – A Mother’s Unexpected Encounter with Politics of Polarization](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Victim-2022-768x432.jpg)