Personified in the cycle of elemental forces, “Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter” makes a complete circle encompassing a constant state of flux. The film chronicles the imagist excursion of a Buddhist monk through the four seasons of life: birth, suffering, death, and rebirth (samsara). Locked away in a floating monastery with his mentor, his is a life that is rehearsed, in the sequestered boondocks, per the traditional Buddhist philosophies- a Dog in the spring, a Rooster in summer, a Cat in the fall, a Snake in winter. Each season is contemplated like a psalm, a turn of the prayer wheel, filigreed with mystic aesthetics of vital truths, like the spokes on a mandala, representing totality and unity, or the wheel of fortune, (known to overturn riotously, dismantling equanimity and certainty).

As in Bodhi dharma, the young monk’s fate is brought upon by himself, though perhaps only subconsciously inscribed by him. Here, the ‘self’ is the locus of squalls and qualms, buoyant on a lone universe, like his little abode on a crystal plane that reflects the skies. At the bank of their home is an old rowboat that ventures into the craggy heart of its immediate surroundings, to commune with a dappled profusion of earthly colours. The glassy clarity of Kim Ki-duk’s motion picture touches the surface with a focus iridescent of soft meditation on life, a meditation that is laced into visual poetry with variegated threads for every season/life.

In the first stage of spring, the wanton apprentice toddles among the ashen boulder-stacked hills, and in a fit of whimsical indulgence, ties a fish, a frog and a snake, individually to a pebble and with malicious joy, watches them writhe. His mentor enacts a similar act of encumbrance on the boy, promising him to free him off the boulder, after he releases the animals from the affliction he had imposed on them arbitrarily as a mightier force. Embodying the conception of ahimsa and karma, the Sisyphean imagery of carrying the burden of turpitude is echoed in the old monk’s words, “you will carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life”.

The frog totem can thrive both in water and land, implying unfettered navigation between the physical, emotional and spiritual planes. It stands as a traditional insignia of healing, although a frog in a well is symbolic of a person lacking in understanding and vision. The frog, upon release, glides agilely into the waters of the creek, keeping alive the upsurge of life in both the somatic and the psychic.

In Buddhism, the fish (often drawn in the form of carp) is a sacred symbol of fortune, fertility, tranquillity and freedom of moment. Since a fish does not close its eyes when it sleeps or dies, an ascetic devotee in Buddhism was expected to reach nirvana with continuous effort like a fish. Connecting with the water element, it represents the deeper awareness of the unconscious or higher self. The death of the fish might simply imply the inhibition of freedom and the self-imposed shackles of guilt, as an undoing, whilst also underlining the universal crisis of civilization, the mind-forged manacles of being ‘tied down’ to worldliness. The snake primarily represents rebirth, due to casting of its skin and being symbolically ‘reborn’- its ultimate mortality anticipates the cycle of samsara being broken.

In the chapter of summer, the adolescent monk guides a mother and her daughter (suffering from a vague ailment) through the forest path to the Buddhist master, so that the latter might be healed. A vibrant rooster shrilly bawls on their home, resonant of desire, the craving of physical connection between the two, and its subsequent consummation. Despite the mentor’s admonition that “possession leads to murder”, the apprentice resolves to take his own road, in pursuit of her, purloining the rooster and the monastery’s Buddha statue, bearing along the sting of desire as well the onus of his religious education.

In the phase of autumn, the mentor returns from a supply run with a cat in his satchel and peruses the record of his apprentice’s criminality in the newspaper. In Korean folkloric belief, the cat is seen as the banisher of evil spirits. People also believed that they were expelled by the flamboyance of gold and red (earth, fire and emotion), hues that proliferated the fall milieu. Furthermore, their mosaic congruence in the plush botanic bounty seeks to pronounce more plangently the wisdom ethics in Buddhism: ‘yellow’ is attributed to equanimity (Ratnasambhava), ‘red’ to compassion (Amitabha) and ‘green’ to peace and protection from harm (Amoghasiddhi). The final stroke of harmony, another ‘tangle’ of the knot, is etched by the ‘white’ canopy of the cairns, and in winter, the snow, symbolizing purity (Vairocana) and the ‘blue’ firmament signifying knowledge (Akshobhya).

Also Related to Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003): 10 Great Films “High on Films” Recommends: 2nd Edition

The day-glow tenor of the wilderness is eclipsed by autumnal murkiness and darkened waters, as the monk returns a fugitive fleeing the law and his own corruption, with a heart floored with animosity and his bloodstained knife. The blackened corners intimate his inherent wrath and primordial hate and ignorance, as well as the role these portents have to play before the final transcendence of clarity and truth. Sealing his senses, he attempts a suicide ritual, until impeded by his mentor, and pushed into penance.

His act of contrition involved embossing the ‘Heart Sutra’ on the monastery’s deck, which his mentor inked in black. It is the sutra which famously proclaims the essence of nonentity, “Form is empty (sunyata), emptiness is form”, a motto that is echoed throughout in the hymn-infused breeze and tasted in the tarn ripples. The master mirrors his apprentice in performing the ritual suicide and immolating himself on the rowboat, thereby putting an end to sentience and suffering. Fire performs a cleansing act, embalming the spirit and transmuting the soul’s attachment to discernment, into a pristine water-like awareness (evident by his teardrops), so that his last act of nullifying the senses develops the core of ‘Avalokiteshvara’, which recites the negations: “no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind; no colour, sound, smell, taste, touch, thing…”

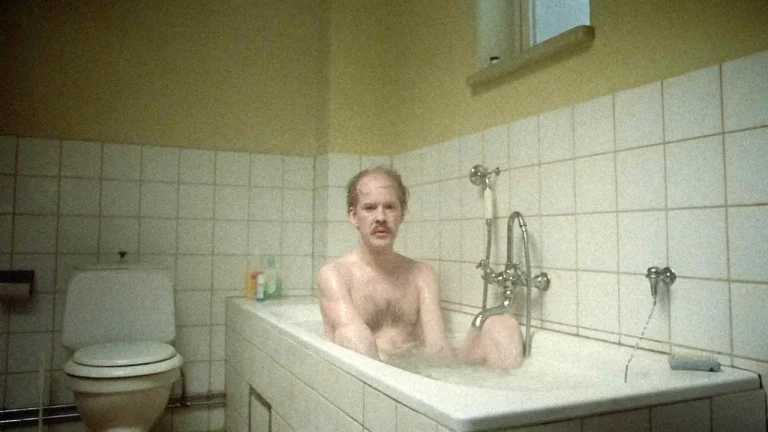

Winter sets in, with a snake swimming from the rowboat into the monastery, and the middle-aged monk returning to the frozen wastes of his abandoned home. His return to the monastery reveals an intrinsic return to the empirical way of life, to reconnect with his roots and ‘self’. He sculpts a Buddha statue out of ice, perhaps bidding to replenish his piety from stagnancy, placing his master’s “sarira” wrapped in red cloth over the statue’s “third eye”, the realm of higher cognizance.

He places the snow-burnished statue under a waterfall, hoping to purge the soul and cleanse it of its sins. Vairocana (who represents purity) is seen as the incarnation of Sunyata (emptiness or the ultimate cessation of everything) in Korean Buddhism; these connotations being symptomatic of the monk’s maturing perspicacity and wisdom, the nearness of grace.

A woman, with her face covered in a shawl, arrives at the monastery with her son, only to leave him behind at night but stumbles into a chasm in the ice. The next day the monk removes the cloth to reveal a stone head of Buddha poised on the scarf. This shot, eerie and enigmatic, is one of the film’s most eloquent images, solemnly evocative of the Japanese Zen scholar Hakuin Ekaku’s aphorism, “All beings by nature are Buddhas, as ice by nature is water. Apart from water there is no ice; apart from beings, no Buddha.”

Enduring his unbroken mediation and self-exercise of discipline, he ties a heavy stone wheel, the burden of samsara, to himself, all the while carrying the statue of Maitreya (the futuristic Bodhisattva who would preach pure dharma) to place upon the summit of the stone hill, surveying the serenity below, a dip in darker translucent blue, a plunge into deeper trenches of awakening. Spring comes flooding back, with the abandoned son now being an apprentice to the monk, repeating the vicious cycle all over again by tormenting a turtle, mirroring his mentor by pushing stones into the oral cavities of a fish, frog, and snake.

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…Spring Again! is a ballad of extreme isolation drummed against the erraticism of weather and the human condition. It brims in scenic perfection that, at times, inundates the screen and washes the senses, dripping dulcet divinity.