The Blue Caftan (2023) Review: During the recently concluded FIFA World Cup, commentator Peter Drury name-dropped a bunch of Moroccan locations- Rabat, Casablanca, Marrakech, and the Atlas Mountains. These names are what would be on the top of one’s tongue when asked to name places from the North African nation, right?

It’s understandable, given that they are popular tourist destinations where revelers flock in droves to experience the culture, embrace it, and carry it back home. However, the same can’t be said for some of the other cities that do not witness the hustle and bustle of tourists. Writer/director Maryam Touzani decided to set The Blue Caftan (Le Bleu du caftan) in one such relatively unfamiliar city from a global perspective: Salé. The aim here may have been to show what is considered acceptable in many parts of the world to be something taboo.

The Blue Caftan tells the story of Halim and Mina, a dutiful couple who own and operate a Caftan tailoring shop in Medina. The proprietor, Halim, insists on quality human perfection over quantity machine work. As the machines accelerated the process, he needed to pick up the pace or risk losing customers to competitors.

As a result, he and his ailing wife hire an apprentice named Youssef to help with quicker Caftan production. Based on the premise of a tailor and his apprentice and the opening scene, I was reminded of Phantom Thread. Did this film go down that path? It may feel like it did. But I certainly didn’t find this film a ripoff of Paul Thomas Anderson’s film. Instead, it offers a contemplative look at emotional attachments fostered in the name of unwavering duty.

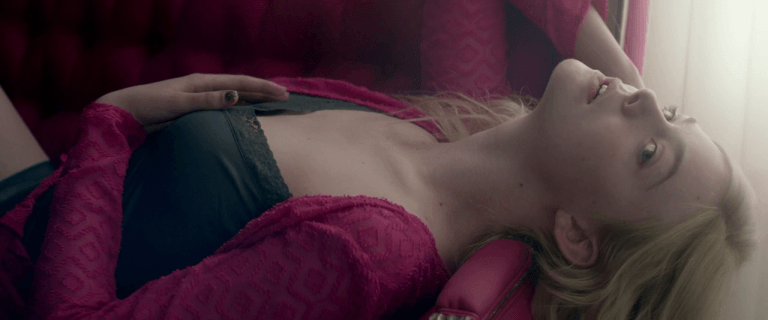

The Blue Caftan opens with a lingering shot of the titular object. The camera glided over the blue silk robe with a clear focus on its smoothness. Audiences only get introduced to the pivotal trio once the working hands place the half-finished blue fabric on a stand. I saw it as a tribute to a fading craft.

The reverence with which Halim treated the caftan positioned it as an important object in the film. Besides captivating the audience’s attention with the regal blue fabric, it permitted the inherent feelings suppressed in the face of cultural hegemony to seep through. The garment also gave one character the idea that freedom for themself can help free someone else. Can The Blue Caftan be viewed as a tribute to the craftsmen, to devotion, and to dutiful love? Yes.

Considering the latent feelings of attraction in a progressing world, I like that writer/director Touzani set her tale away from the premier Moroccan cities. Salé could have progressive individuals. However, the main cast or extras did not feature tourists or ex-pats. It explained why the desires couldn’t emerge.

Touzani also used the Caftan to showcase an evolving world. Firstly, a Caftan is traditionally a unisex garment. Nevertheless, in The Blue Caftan, it is shown as something preferred mostly by women. This was made apparent through the dialogue present throughout the film. One instance where Mina shut down a customer showed it in terms of mass production being the norm and dismissing an age-old adage that may irk individuals in the customer service business.

Saleh Bakri’s character of Halim doesn’t say much. But like an introvert, he has a flurry of thoughts racing through his head. It can be seen as his eyes convey realization, remorse, restraint, and regret. Touzani allowed the emotion and conviction of the lead character to show when restraint was required, as evidenced by the trickle of a tear running down his face. A silent defiance is present in Halim as he becomes an artist to cope due to the lack of acceptance. Do coping mechanisms push people to hone their skills so much that they attain perfection?

Mina’s (Lubna Azabal’s) transformation is brilliant as she progresses from being stern to a welcoming individual. Every fiber of her being exudes a sense of knowing, which she tests in order to get a clear idea. Subsequently, through this, she understands prolonging her pain only adds to the pain of duty. Because of this character nature, the emergence of Halim’s suppressed emotions took on greater significance.

In the absence of words, Virginie Sudrej’s camera captures the exact emotions that would allow the audience to comprehend the three leads. Moreover, editor Nicolas Rumpl inserts breaks at the right moments in some places to let the reaction be witnessed with the action, which helps audiences consume the non-verbal dialogue. At some points, the film jumped too much or cut quite awkwardly. Was that a way to convey Mina’s jealousy?

One could look at it that way. Another point of view is that it left Youssef and Halim’s time at the shop open to interpretation. A scene later drove home the point that only one interpretation was correct, thereby maintaining that Halim did his duty. However, the satisfaction of urges came from emotionless attachments.

The Blue Caftan (2022) hits cinemas on February 10.

![Swallowed [2022]: ‘Fantasia’ Review: The Kind Of Messy Queer Horror We Need](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Swallowed-768x405.jpg)

![8 [2019]: ‘Fantasia’ Review – Chilling, Terrifying and Flawed Folk Horror](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/8-Fantasia-highonfilms-768x322.jpg)