Stories invite reflection, embedding moral lessons deep within the essence of our being. As Chuck Palahniuk observes in “Haunted,” readers consume lives much like theatres absorb audiences. Novels aim to provoke – whether through tears or nausea – drawing readers into the emotional world of the author. The climax resolves the excruciating narrative, leaving the audience to wrestle with the emotions it evokes.

Wataru Misaka stands as a wanderer, a refugee seeking to illuminate his path through the darkness, striving to restore faith in forgiveness. Born a Nisei – a term for second-generation Japanese immigrants – he was part of a community that left Japan in pursuit of the mythical “land of dreams and promises.” Yet, these refugees grew up as American citizens, belonging to a homeland that often treated them not with pride but as scapegoats.

Racial tensions remain stark, compelling all individuals of Japanese descent – regardless of citizenship – to face displacement from their homes. The United States once envisioned as a shimmering island of boundless opportunities, often fell short of its promise. Second-generation Japanese Americans, whose parents endured hardship to escape an imperial regime, made sacrifices for the prosperity of their children. “People leave you alone; they treat you like you’re different, and that’s true – because we are different,” reflects Wataru Misaka in the documentary, “Transcending: The Wat Misaka Story,” directed by Bruce Alan Johnson and Christine Toy Johnson.

Born in Ogden, Utah, Wat grew up in poverty alongside his two younger brothers. Their family lived in the basement of a saloon where his father worked as a barber. Recalling his gritty surroundings, Wataru describes the infamous 25th Street: “A really rowdy road. There were a lot of beer halls and brothels.” Wataru Misaka lived through virtual apartheid, a stark portrayal of racial discrimination and cultural prejudice inflicted by white Americans on immigrants striving for a better life. Following the death of his father, Misaka left school to shoulder the role of provider, becoming the family’s anchor. His younger brother Tatsumi later reflects, “My mother was a hero in our family. She raised us with no skills or trade.”

Sports became a beacon of hope, a testament to human resilience and the transformative power of purpose. Basketball, in particular, served as a lifeline, offering an escape from the harsh realities of systemic oppression. It also became a medium to challenge the societal norms that sought to alienate immigrants. These athletes, survivors of an imperialistic state’s exclusionary policies, stood as symbols of perseverance. As Paul Osaki, Executive Director of the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California, aptly notes, “A lot of things happened in the community – whether through basketball or Boy Scouts – they were against the law”.

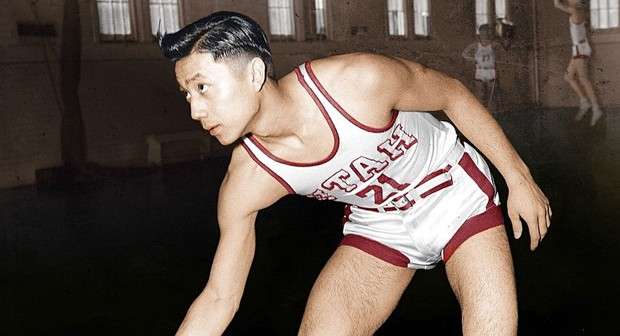

Wataru Misaka emerged as a standout athlete early in his life. At Ogden High School, his basketball talent earned him the opportunity to graduate, provided he joined the varsity team. The young Asian star led the squad to a State Championship in 1940 and a regional title the following year. Misaka then attended Weber College, where he continued to shine. By the end of the season, his team triumphed in the Junior College Tournament. Reflecting on his performance, he says, “I was the high point man, and my best shot was coming across the line. It won me the MVP for that tournament”.

Misaka later enrolled at the University of Utah, where his journey was marked by both success and adversity. As a guard, he stood out not just for his skill but also for his ethnicity in a predominantly white roster. Racial slurs from hecklers were a constant challenge. Despite his talent, Misaka often didn’t start games, likely due to concerns over backlash against the coach for fielding an Asian player. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, drafted by War Department official Karl Bendetsen. This directive authorized the forced relocation of Japanese Americans to internment camps across the country. Though framed as a military necessity, the order was steeped in racial prejudice, effectively segregating and marginalizing entire communities based solely on their ancestry.

Amid the growing climate of fear, General John L. DeWitt, driven by wartime paranoia, became a vocal advocate for the removal of all individuals of Japanese descent aged 14 and older. His infamous remark –“It makes no difference whether they are nationals or not” – dismissed citizenship as meaningless, further solidifying the discriminatory nature of the policy. The University of Utah’s basketball team earned a coveted spot in the prestigious National Invitation Tournament (NIT). Despite being eliminated in the first round, the team seized a remarkable second chance to compete in the NCAA Finals. In a thrilling game, they triumphed over Dartmouth, with Wataru Misaka delivering an outstanding performance that helped secure the championship title.

Just two nights later, the Utes played an exhibition game at Madison Square Garden in New York City against the NIT champions. The warm reception in the Big Apple electrified the crowd, who enthusiastically cheered for Misaka. To many, Wat became a symbol of hope and progress – the embodiment of Japan’s resilience and the possibility of breaking free from the grip of prejudice. Reflecting on his generation, he remarked, “So many Nisei, the sandwich generation, had their Issei parents to care for and their own children to raise.” The atomic bomb dropped, and with it, the war came to an abrupt and devastating end. The destruction marked the collapse of Japan’s imperial reign, leaving its cities lifeless and barren – grim landscapes resembling a dystopian tale of unending conflict.

As Captain Gotoh poignantly states in Patlabor 2: The Movie, “An unjust peace is still better than a just war.” Wataru Misaka’s post-war journey reflects this sentiment. Enlisted in U.S. intelligence as a staff sergeant, his role involved understanding the moral toll of the bombings on civilians. However, wearing the American uniform brought him scorn from Japanese citizens, who viewed him as a symbol of betrayal. Reflecting on his experience, Misaka remarks, “I was a man without a country.” After two years in Japan, Wataru Misaka returned to Utah and rejoined his team. Together, they secured a second national championship in four years and, later, triumphed in the NIT Finals against Kentucky at Madison Square Garden. The Big Apple adored the quick and skillful Misaka, who became a crowd favorite.

In March 1947, during the inaugural BAA Draft – later known as the NBA – Misaka was selected by the New York Knicks. The team’s general manager, Ned Irish, chose him in part because of his growing popularity. However, the roster was already crowded with three guards, two of whom were established starters, leaving Misaka with limited opportunities to showcase his talent on the court. Wataru Misaka made history in 1947 as the first non-Caucasian player to compete professionally in basketball, debuting in the same year Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. During his brief tenure with the New York Knicks, Misaka played three games and scored seven points. Despite his trailblazing presence, the team unexpectedly released him. Reflecting on this moment in a documentary interview, he admitted, “I don’t know if being cut was a big surprise. Maybe it shouldn’t have been.”

Racism was a pervasive issue at the time, and immigrants faced constant struggles with both discrimination and prejudice. Despite receiving an offer from assistant coach Abe Saperstein to join the Harlem Globetrotters, Misaka declined. For an Asian American, life in the United States often meant being viewed not as an equal but as a perpetual outsider. Although Wataru Misaka’s professional basketball career was brief, his journey became a source of inspiration for countless non-American individuals. His groundbreaking achievements sparked a wave of enthusiasm, with thousands of children joining basketball programs to build friendships and pursue careers in sports.

Ernie Ferrin, Misaka’s former Utah Utes teammate and close friend, offers a profound perspective on the impact of athletics. He believed that sports transcend the divisions of war, breaking down cultural and linguistic barriers. In this light, Japan’s efforts toward inclusion and reconciliation – despite the atrocities of conflict – highlight the power of sports to unite even in the aftermath of a belligerent state’s aggression. After retiring from basketball, Misaka completed his degree at the University of Utah, which later honored him by retiring his jersey number 20. From 1948 until 1981, he worked as a mechanical engineer. Reflecting on his life, Misaka humbly remarks, “The way it was and the way they treated me, I was just another basketball player.”

![1BR [2020] Review – An ingenious horror-thriller that crafts a satisfying rehash of genre tropes](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/1BR-Movie-Review-highonfilms-1-768x322.jpg)

![A Thursday [2022] Review – Yami Gautam becomes the Knight In Shining Armour Of her Revenge saga](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/A-Thursday-2022-768x427.jpeg)

![A Matter of Life and Death [1946] Review: A Timeless Treasure of British Cinema](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/a-matter-of-life-and-death-screenshot-1-768x558.jpg)