Directed and co-written by Lynne Ramsay and based on Lionel Shriver’s 2003 novel of the same name, “We Need to Talk About Kevin” (2011) has remained one of the most talked-about movies of the last decade. The way it stages both the build-up to—and the aftermath of—a fictional school massacre, and how it unravels through the mother of the perpetrator, is so chillingly real and inwardly grounded that one might easily believe it’s based on a true incident.

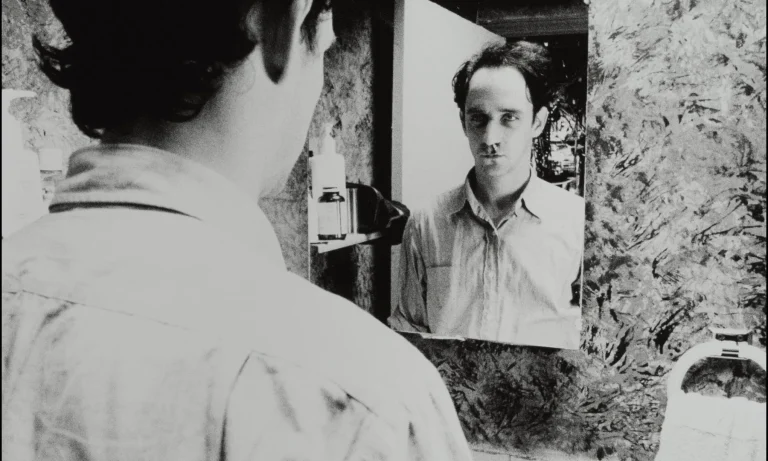

The cinematic language Ramsay uses to examine familial blindness to sociopathy, societal blame-shifting, and the anatomy of trauma is so disarmingly simple and universal that it cuts deep. The film feels like a reel of a grieving woman’s life projected through a cracked mirror. And that’s not just aesthetic—it’s embedded deep within the storytelling. Eva’s non-linear character sketch holds nothing back that is crucial to understanding where her depression stems from, drawing us into a closeness that’s as aching as it is terrifyingly human.

Its mode of storytelling may lose some novelty with evolving technology, newer sensibilities, and a wider range of emotionally raw stories being told today. But its dissection of emotional and physical terrorism within families still lands with sharp precision. Its study of trauma and lopsided marriage dynamics remains just as powerful, and because of its aural minimalism, its moments of pure frustration and fractured empathy hit in their rawest form. Tilda Swinton’s Eva isn’t a performance so much as an exposed nerve. And that, in itself, is messy—because something else crawls under your skin just as easily: Ezra Miller’s Kevin, whose nonchalant cruelty and casual violence are portrayed with such eerie normalcy that it’s hard not to see glimpses of real-world perpetrators in him.

The thriller part is easy to follow. It’s the emotional and psychological turbulence that’s harder to hold. So here’s our attempt to break that down.

We Need to Talk about Kevin (2011) Movie Plot Summary and Synopsis:

What is Eva’s current life like after the tragedy?

The film opens with the visual of a fluttering curtain inside a dim, isolated apartment. It then transitions to the chaos of Spain’s La Tomatina festival, where tomatoes fly and bodies collide in a frenzy of red. Amid the crowd, we see Eva Khatchadourian for the first time. She now lives alone in a rundown white house, its exterior vandalized with red paint that stubbornly refuses to wash off. She quietly takes a job at a nearby travel agency. In her solitude, past and present blur. Once a successful travel writer, Eva now lives in the shadow of something far darker. She visits her teenage son, Kevin, in prison. As she reflects, the reason becomes clear: Kevin has been convicted of a mass shooting at his high school.

How does Eva cope with the aftermath of Kevin’s crime?

Eva had rushed to the scene the evening it happened. What she witnessed was chaos—wailing mothers, stunned siblings, families breaking down. That trauma never leaves her. Even as she returns to her routine, the hostility is constant. A grieving mother slaps her across the face on the street. At a supermarket, another woman smashes her eggs in cold fury. She walks through the world as if marked, silently despised. Yet she bears it with grace, absorbing the public hatred without protest.

What was Kevin like as a child, and how did his parents respond to him?

Her memories drift back to when she met Franklin, the man she eventually married. Despite being hesitant about motherhood, Eva agrees to have a child. From the beginning, Kevin is difficult. As a baby, he cries relentlessly, but only around her. When he grows older, he ignores her so completely that Eva fears he might be deaf. But the ENT doctor confirms his hearing is perfectly fine. Kevin persistently rejects Eva’s affection and displays no real interest in anything. With Franklin, however, he is charming, playful—the perfect son. Franklin, ever the gentle optimist, dismisses Eva’s concerns outright. His catchphrase? “He’s just a kid.”

When did Eva begin to fear Kevin’s violent tendencies?

One day, Kevin resists toilet training with deliberate stubbornness, driving Eva to a breaking point. In a moment of rage, she hurls him against the wall, fracturing his arm. At the hospital, the doctor calls Kevin a brave little boy. Kevin, ever calculating, lies to Franklin, claiming he simply fell. He uses the injury as leverage, emotionally manipulating Eva. In time, Eva becomes pregnant again, possibly longing for a child who might love her back. She doesn’t tell Franklin right away. A baby girl is born, and they name her Celia.

At one point, Kevin comes down with a fever and, for the first time, shows warmth towards Eva, letting her read Robin Hood to him. But the tenderness vanishes once he recovers. Soon after, Franklin gifts Kevin a bow and arrow and begins teaching him archery. The act, seemingly innocent, carries a quiet menace in hindsight.

As Kevin grows, Eva tries to reconnect. She takes him on small outings, hoping to bridge the void between them. But Kevin mocks her every attempt. Some time later, Celia’s pet guinea pig mysteriously disappears. The next day, Eva discovers the remains jammed deep in the garbage disposal. She uses a drain cleaner to unclog it. Not long after, Celia is left blind in one eye, burned by the same cleaner while Kevin was supposed to be watching her. She now wears a glass eye. Eva is convinced Kevin hurt her on purpose, but Franklin brushes it off again. He refuses to believe his son is capable of cruelty. Tired of Eva’s accusations, Franklin starts talking about divorce. Kevin, of course, overhears the conversation.

We Need to Talk about Kevin (2011) Movie Ending Explained:

What exactly did Kevin do on the day of the massacre?

In the present, Eva runs into one of the high school shooting survivors. The boy speaks kindly to her, but Eva is too anxious to receive it fully. At work, her colleague Colin offers some help and minor conversation, though most of her coworkers just stare. At the agency’s Christmas party, Colin makes a move on her. When she refuses, he turns cold and verbally insults her. Eva walks away, humiliated. The past surges up again.

She remembers the day of the massacre vividly. It was three days before Kevin’s 16th birthday. Using bike locks he had ordered weeks in advance, Kevin traps several students inside the school gymnasium. Armed with his bow and arrows, he kills them one by one. Eva watches the aftermath unfold—the victims’ bodies being carried away, Kevin being taken into custody. When she returns home, a final horror awaits: Kevin has murdered Franklin and Celia as well.

Also Related: The 10 Most Unsettling Movies You’ll Ever See

What happens when Eva finally asks Kevin why he did it?

On the second anniversary of the killings, Eva visits Kevin in prison. He looks different now—quieter, more fragile. As he prepares to be transferred to an adult prison, the swagger is gone. Eva asks him the one question that’s haunted her: why? Why did he do it? Kevin stares back. “I used to think I knew,” he says, “but now I’m not so sure.” A guard informs them that the visit is over. Eva gets up, walks to her son, and embraces him. Then, silently, she walks away.

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) Movie Themes Analysed:

Motherhood as a Site of Alienation and Moral Ambiguity

For a long time, even the most psychologically dense pieces of art about institutions of family and society have framed motherhood as something intrinsic, something that arrives seamlessly with childbirth and is instantly sanctified. Of course, contemporary storytelling has increasingly deconstructed this ideal, offering a surge of narratives about reluctant, absent, or disillusioned mothers, haunted by pregnancies they never prepared for.

Lynne Ramsay’s potent film was among the early, unflinching initiators of this movement. The point becomes even more piercing through Tilda Swinton’s nerve-wracking performance, which pits Eva’s emotionally remote, unsentimental approach to maternity—and her poker-faced exasperation—against the culturally inflated fantasy of maternal warmth that supposedly arrives the minute you shove a piece of meat out of your vagina.

Much of “We Need to Talk About Kevin” is constructed like a horror film, and the horror is sourced not from jump scares or gore but from the existential dread of raising someone you cannot bring yourself to love. It paints a worst-case scenario in which the child actively rejects your every offering of affection, dismantling the very premise of familial intimacy. Ramsay doesn’t flinch from moral gray zones.

The central ambiguity hangs heavy: How responsible is Eva for what eventually happens? Was she complicit because she didn’t discipline Kevin enough, or failed to leave when she sensed the rot? Or was she just condemned to nurture something inherently corrosive—someone born without empathy? The aesthetics push you toward the latter, but the film is careful to leave the “nature vs. nurture” balance up to interpretation.

What haunts most is the film’s intimate, almost whispering confrontation with the guilt of wishing you’d never had a child. From the moment Eva first holds Kevin, whose relentless crying pierces her spirit, there’s a dull, defeated look in her eyes—and it barely shifts by the final frame, where she embraces the teenage version of that same shrieking infant.

For Kevin, this might be a coming-of-age narrative gone psychotically wrong. For Eva, it’s a descent into limbo. She becomes a woman condemned to weather public judgment for something she had been silently resisting for years. The circumstances are so merciless, so lopsided, that blame finds no suitable vessel—not even her oblivious, enabling husband. The ghoulish, almost medieval way in which society gawks at Eva becomes a precise critique of our collective need to scapegoat women when they don’t live up to the fantasies we’ve foisted on them.

The Banality of Evil and the Performance of Normalcy

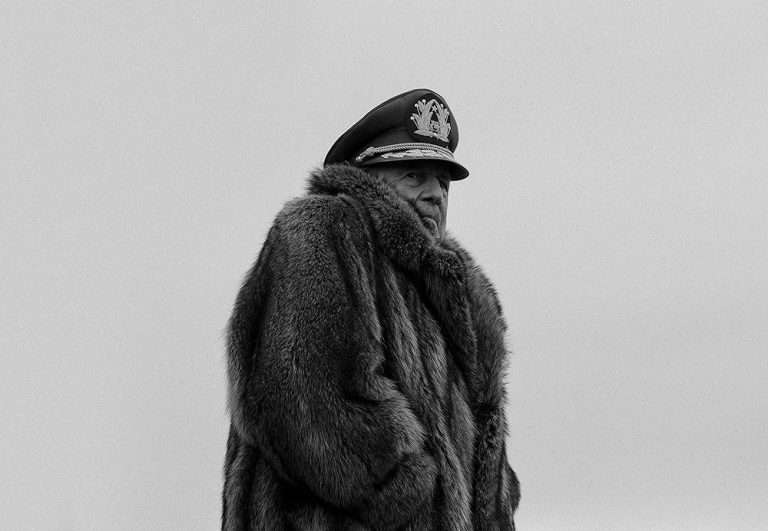

The Hollywood archetype of a deranged killer comes with convenient signposts: a visibly unstable psyche, a backstory of abuse, and a red-flag trail the system fails to intercept. But Kevin doesn’t touch that stereotype. That’s what makes him terrifying. He’s calculated, cold, and disturbingly performative—with a sleek, functional intelligence that could pin you to your chair if he decided to dissect your weaknesses over dinner. His nihilism isn’t mythic or dramatic—it’s banal. It is precisely what modern-day terrorists are made of, if one reads into how they operate: he casually picks up archery to bond with his father, mimics charm when needed, and drip-feeds manipulations over time without ever lifting the mask.

Kevin displays a chilling indifference to the idea of morality itself. Anything emotionally sincere or ethically clear registers as artificial to him. Violence, on the other hand, speaks to him directly—because it’s primal, potent, and immune to emotional complexity. Under the guise of childish rebellion, he develops a sophisticated appetite for cruelty. And why wouldn’t he? It works. It speaks louder than any constructed institution or value system. The scariest part is how he weaponizes charisma. With his father, he’s sociable and affectionate. With Eva, whom he perceives as lost or fractured, he turns into a sadist. And because the same womb bore a more lovable sibling, Celia, he punishes her too. Not with tantrums—but with surgical intent.

This is where sociopathy slips through undetected—because suburbia, by design, masks ugliness with routine. It deodorizes dysfunction. There’s no psychology lesson necessary; it’s just how these spaces work. The more monstrous the behavior, the more easily it’s hidden in plain sight. The cinematography and production design use this spatial grammar cleverly, furnishing Kevin’s evil with the polish of domestic normalcy, until it all curdles.

Memory, Trauma, and the Architecture of Guilt

We Need to Talk About Kevin’s elliptical, nonlinear structure isn’t a stylistic quirk; it mirrors the ruptured state of Eva’s consciousness. Time loops. Events bleed into one another. The past is not just revisited—it invades. Trauma here functions less like a wound and more like architecture: lived in, rearranged, impossible to escape. The red paint on Eva’s house, splattered like blood across its white exterior, becomes a physical manifestation of her internal chaos—one she’s forced to live with long after the crowd has moved on.

What’s most disarming is the unreliability of memory. Ramsay doesn’t offer a clean chronology because Eva herself can’t construct one. She combs through her past with surgical desperation, trying to trace the origins of Kevin’s descent, but memory here is unstable, emotional, and subjective. It edits, distorts, and loops. There are no epiphanies, no neat conclusions—only repetitions of questions that have no satisfying answers. In the absence of certainty, guilt grows roots.

By the time “We Need to Talk About Kevin” (2011) ends, Kevin still hasn’t offered an explanation for his actions. “I thought I knew. But now I’m not so sure,” he shrugs. It’s a devastating anti-climax, but also the most truthful note the film could end on. Some traumas don’t culminate in clarity. They just settle in, like rot in the walls. For Eva, that’s the real punishment—not the massacre, not the isolation, but the fact that she has to keep living with questions that no longer even want answers.