“This is the job that we do–finding that visual metaphor and bringing it to life” – BIFA-winning director of photography Jamie D. Ramsay

Since premiering to acclaim at the 2023 Telluride Film Festival, Andrew Haigh’s “All of Us Strangers” has emerged as a dark horse in the Oscar race. Much of the film’s resonance is owed to cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay’s thematically and narratively evocative compositions. I was lucky enough to chat with Mr. Ramsay shortly after the announcement that he would be receiving this year’s cinematography prize from the British Independent Film Awards.

Our discussion with Jamie D. Ramsay touches on the multi-disciplinary cross-section of artists that inspired his vision for “All of Us Strangers”, using cinematography to tell rather than just deliver a story, and a recent film that’s got him buzzed on cinema.

Read an edited transcript of the interview below, or listen to the original conversation on Spotify

Ron Meyer: In past interviews, you’ve talked about the right script opening a tap of ideas and allowing the film to form visually in your brain. When during your first look at Andrew Haigh’s script for “All of Us Strangers” did that moment occur?

Jamie D. Ramsay: When I read “All of Us Strangers” for the first time, it was one of those rare moments where I read it in one go, and that doesn’t happen often. Reading a script is something that I stop and start, stop and start, and kind of absorb. But “All of Us Strangers” was a once-off experience. It was within the first act where I was hooked, and it’s a very poised journey that you go on with the story, and it was poised and meditative even in script form. I’ve heard it described as being in a theater state-of-mind, where you’re almost able to access grief and past issues that are locked up within you. And when I read the script itself, it had me on the brink of tears in moments, and I knew – I knew that I was accessing stuff that I had been through, and I knew then that this was an important thing to do. And it was important for me to do it, because I was able to definitely channel a part of me that made it relevant and real, and hopefully, has left something important behind.

Ron: I know that in order to channel those feelings, you prefer to take inspiration from still photography and paintings and poetry rather than other movies. Can you talk about some of the work that guided your creative process on this film?

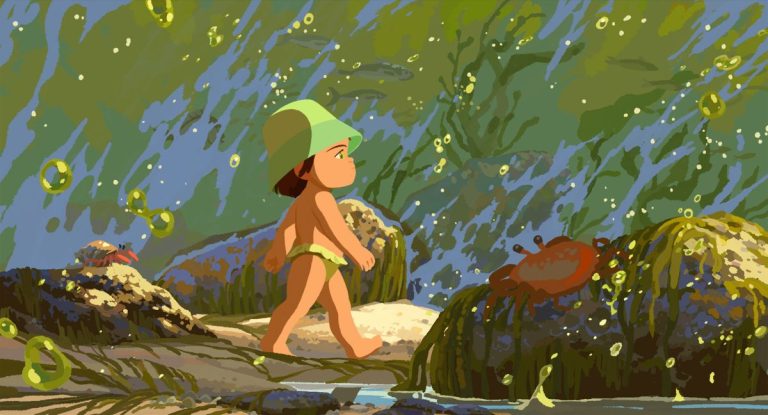

Jamie: Absolutely. Obviously, when going through the process of building your film’s aesthetic fabric, as a creative, there are things that you reference and that give you energy and inspiration. And for me, imagery, whether it’s in photography or painting, I definitely pull a lot from that – the written word, poetry, as well. But with regards to “All of Us Strangers”, I remember looking at Francis Bacon’s work and thinking that there was a psychology there that was really interesting – a sort of distortion of self-image that I felt could be a way for us to represent Andrew’s view of himself. With regards to that idea of self-representation, the photography of Saul Leiter is also something that I really looked upon. Saul Leiter is a photographer who really uses reflection and the objective lens in a way that feels very personal. The idea of the cinematography feeling personal and representative of one’s own eyes looking at oneself was very important. Having said that, there were also two movies that we did look at, that did feel like they represented a clash of feeling that could help us – Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers” and Studio Ghibli’s “Spirited Away”. Energetically, there was a collision of those two films that felt right to me.

Ron: That’s actually a good segue into my next question: I’ve heard you describe film as something that’s built on binaries. Perhaps you can elaborate a little bit more on what you mean by that and, specifically, what you find to be the binaries in “All of Us Strangers”.

Jamie: For me, when I take a film, there has to be certain trigger points emotionally that make the film speak to me. And when I looked at “All of Us Strangers”, I thought, looking at the binary of loneliness in a space that’s representative of potentially one of the busiest places in the world per capita, and just the paradox of how loneliness is amplified by busyness – and that’s something that I personally related to when I moved from South Africa to London seven years ago. Living in South Africa, I had a whole world built. I knew where I lived, I had great people around me, I knew exactly what was going on; when I moved to the UK, I very suddenly was plunged into this ocean of extreme loneliness. I was completely out of my depth, I knew nobody, and it was a very cold environment. I was in one of the busiest places in the world, and I felt the most loneliness. For me, that’s a driving binary – the paradox of, “How can you feel this loneliness in such a busy place?” I really identified with that. And another binary that’s really interesting is the sense of loss, and the loss of oneself and identity and confidence. Ultimately, you exist, you exist in the form that you’ve always existed, but all of a sudden, you’re finding yourself in a position where you don’t know who you are anymore, and you’ve lost that self-connection.

Ron: You capture that literally in the film. You were talking earlier about Francis Bacon and self-distortion, and that’s not just a philosophical idea in the movie. You literally frame Andrew Scott to appear as if he is being – there’s him in the elevator of his apartment block with the infinity mirror where it looks like he’s being stretched across dimensions. There’s a moment that almost bends toward a bit of horror when he’s on the train looking at a reflection of himself as a boy, and it’s almost like these delicate light waves that form him are being stretched apart and he’s losing his identity.

Jamie: Absolutely. This is the job that we do – finding that visual metaphor and bringing it to life. Yes, it can be a very practical process sometimes, but if the consciousness is born in poetry and understanding, then it comes across well. This idea of the distorted image was just about what platforms could we find that we could naturally and subtly sow them into the film so that it wasn’t an overt and out-of-picture experience. It kind of went smoothly with everything else we were doing. If you’ve ever ridden the tube in London, you’ll know that those windows – there hasn’t been a night out where I haven’t gazed into those windows and thought how interesting they were. You kind of play with that distortion. Perhaps on some days, if you’re having a worse day than others, your mind kind of wanders.

Ron: The film’s centerpiece visually, I think it’s safe to say, is the ketamine sequence. How did you form the visual language for that scene? Did you decide how you were going to shoot it while reading the script, or did you and Andrew Haigh collaborate on it during production?

Jamie: With regard to the club sequence and the whole thing with the ketamine – the advent of the ketamine was actually quite useful because everything else was based in sort of the supposed reality of the story. But once we introduce ketamine, it allowed me to really push the sort of visual poetry of where the lights were going, how the camera was moving. Obviously, it’s important to know what ketamine feels like if you’re ever going to shoot a club sequence that represents a certain experience. You should show what it feels like, and how better to represent ketamine and the sort of journey you go on when you’ve had a night out like that? This idea of going on a journey that the whole peripheral experience narrows into a singular wormhole, and the person that you’re with or the person that you’re having this experience with – it’s almost like you guys are in a time warp and in a wormhole. And just about how to represent, and having the presence of Andrew and Paul, and them playing off each other in such a personal way – breaking the fourth wall using the movement of the camera to understand the sort of leglessness of that experience, it all sort of came together in this perspiration of a scene that was the club sequence.

Ron: Given our brand, we like to ask guests about their cinematic highs, and I guess it’s appropriate that I’m asking this question after we just discussed ketamine. Because we’re also discussing this movie one year after you were in Poland to accept the Bronze Frog at CamerIMAGE for “Living” and only a few days after the conclusion of 2023’s edition, I’d like to remix the question and ask what you’ve seen this year that’s given you the sort of buzz only a great piece of cinema can.

Jamie: I haven’t felt this buzz a lot lately. I haven’t been able to watch everything that’s out there at the moment, but there is stuff out there like “The Zone of Interest”, which is by a director and cinematographer who are two of the most relevant auteurs of our time. But there is also a lot of stuff that, because it’s by famous people, has this glow around it. But it doesn’t catch me because it’s just a little bit common in its language. But there is stuff out there that’s interesting, but it’s kind of rare at the moment. Not a lot is grabbing me of late. Perhaps I need to widen my scope in terms of what I’m watching, but I hope that my film is one of those. To be honest, watching my film at CamerIMAGE was emotionally quite a moment because of the catharsis of making it follow through to the viewing experience.

![Two for the Money [2005]: Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Two-For-The-Money-featured-768x432.jpg)

![Extinct [2021] Netflix review : Doughnut-shaped animals’ fight for survival is too uneven to register its case](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Extinct-2021-Netflix-768x432.jpg)