Although my review of Alex Garland’s “Civil War” was anything but a glowing endorsement (to put it mildly), the film does offer a distinctly modern examination of how we view the unforgiving carnage of warfare. Part of its distinction admittedly comes from how Garland consciously chooses an apolitical stance that results in a rather ineffective overall film. However, from this point of origin, we can trace more than enough points of similarity and influence that achieve what “Civil War” fails to do. This list isn’t necessarily a list of “8 Movies to Watch If You Liked Civil War” so much as it is a list of films that take similar ideas and run with them more adequately.

Whether focusing on the tribulations of war, the complications of neutrality, or the power of photography—and, in the best cases, all three–-the films listed below will hopefully provide a more nuanced accompaniment to this sort of material to either complement your liking of “Civil War” or outright make up for where it lacks. Without further ado, here are 8 movies like “Civil War”:

1. Full Metal Jacket (1985)

There is no shortage of seminal war films to lead into your viewing of “Civil War”—or cleanse your palette if you find Alex Garland’s vision utterly diluted—but what better place to start than with the master? Stanley Kubrick, ever the perfectionist, meticulously crafts a portrait of human chaos in “Full Metal Jacket,” one of his final films.

A view of American soldiers in the Vietnam War, Kubrick splits his film into two distinct halves: the grueling cadet training and the horrifying outcome of sending those desensitized boys to carry out the ensuing carnage. It’s virtually impossible to make a Vietnam War film that strays from politics (spoiler alert: there will be more to come), and “Full Metal Jacket” is no different, expressing Kubrick’s fascination with the fallibility of human compassion when pushed toward the achievement of a greedy, short-sighted agenda.

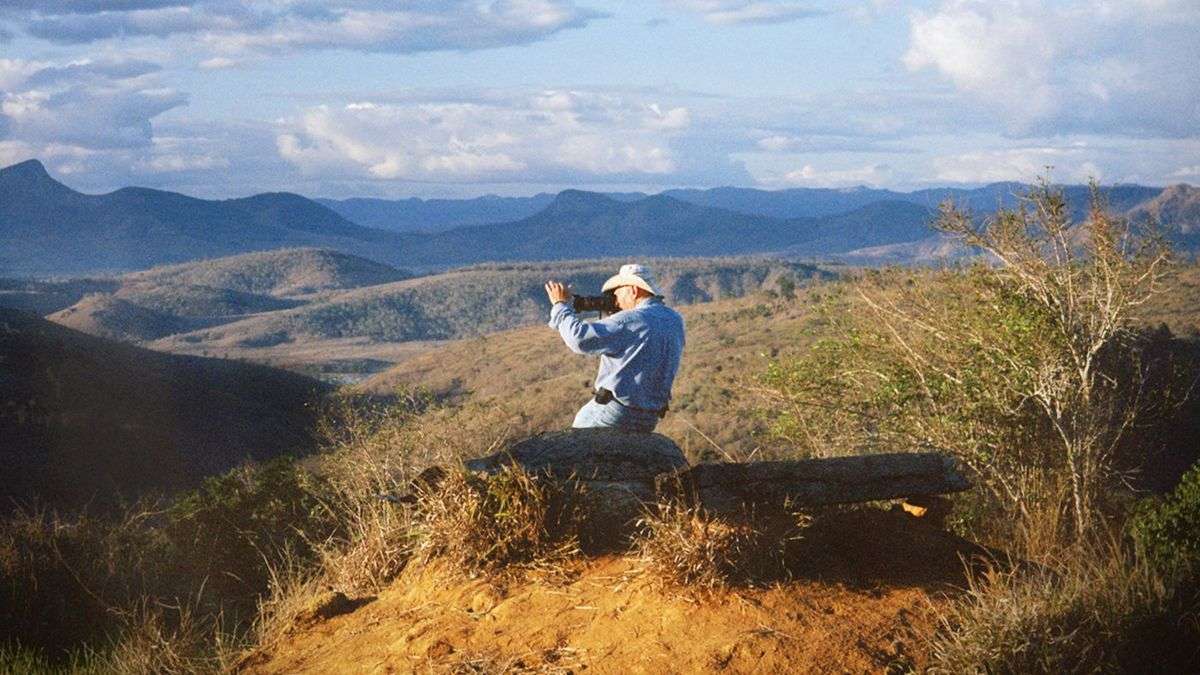

2. The Salt of the Earth (2014)

Through a documentary on the power of the photograph seen through the career of Sebastião Salgado, Wim Wenders (who just made waves last year with two excellent films), and Salgado’s own son, Juliano examines the importance of documentation and the suffering that often comes concealed behind the beauty of an image. A photographer in his own right, Wenders is patient with Salgado’s medium, giving ample time to examine both the photos themselves and the hardships and beauties that were encountered in their taking.

While it doesn’t directly focus on the horrors of war in the same way as Garland, “The Salt of the Earth” gives ample space to unpack just how photography works as both a window into the majesty of the rest of the world and a blinding screen that obscures its true horrors. Salgado gets intimate with his commentary here, and Wenders and Salgado Jr. find themselves more than willing to give him that required space to explore these double-edged facets of the medium to which their subject has dedicated his life.

3. Blow-Up (1966)

Another film more concentrated on the aspect of photography than anything related to combat, Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blow-Up” may be just as polarising as “Civil War,” but it is so for entirely different reasons. Applying his usual contemplative, airy stylings to what’s ostensibly a mystery thriller, Antonioni revels in the silent methods of a party-ready fashion photographer who realizes he may have captured a murder in the background of one of his compositions.

Not content to make a standardly fulfilling entry in its genre with conventional progression, “Blow-Up,” in a way, does complement “Civil War” in the sense of provoking thoughts about the value of detail. But where Garland appears disabled by an inability to commit to a sense of political context, Antonioni luxuriates in keeping his viewers in the dark for the sake of creating a looming sense of unease. We are given just as much context as the protagonist, and that’s what makes it all the more terrifying by the film’s controversial end.

4. Hearts and Minds (1974)

Yet another chronicle of the Vietnam War, “Hearts and Minds,” directly documents the political implications of America’s involvement in Western capitalist overreach. Like “Civil War,” Peter Davis’s documentary becomes a document of the horrors involved in capturing atrocities for the people sitting comfortably back home. The films differ in Garland’s preference for the people behind the camera while Davis keeps his eye on the terrors in front of it, but “Hearts and Minds” nonetheless communicates a textured sense of danger and futility that may just escape his more neutral counterpart.

Context, or a lack thereof, is everything. While Garland traffics in the latter to achieve his disorienting effect, Davis knows that a truly impactful war film engages in the former to remind viewers precisely what’s at stake. In the case of “Hearts and Minds,” it’s all in the title.

5. Eye in the Sky (2015)

A war film steeped in the political environment of its moment in time, “Eye in the Sky” makes for a useful companion piece to “Civil War” precisely in its focus on the sense of removal perpetrators have from the innocent lives they hold in their hands. With the added dimension of the importance of technology mediating that distance—here, surveillance cameras and drones rather than traditional photography—Gavin Hood spends the majority of his film exploring that distance in a way that distinctly criticizes those involved, creating food for thought beyond its sense of spectacle. Following a group of high-ranking British officers tasked with authorizing a drone strike on potential weapons suppliers that risks high civilian casualties, “Eye in the Sky” makes the moral quandary of its premise the entire point, providing a crucial vantage point in any discussion of the optics of war.

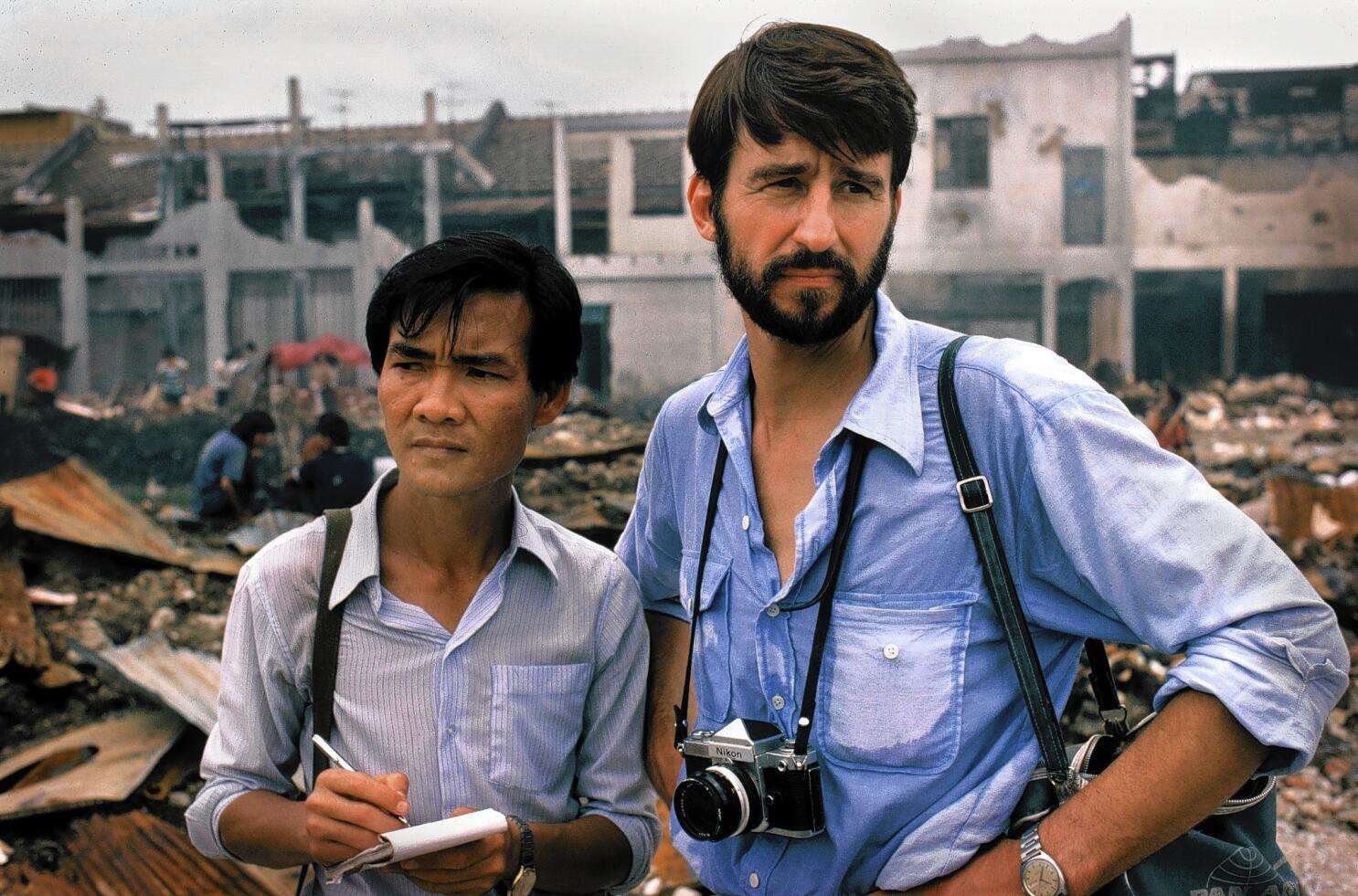

6. The Killing Fields (1984)

“The Killing Fields” is probably the most directly analogous film to “Civil War,” itself an exploration of the dangers of war journalism. An exploration of the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia in the mid-1970s, Roland Joffé’s film gives just as much attention to the dangers of the profession as it does the privilege that comes with being an onlooker from the outside versus one living in the midst of this constant danger.

In a way, this makes “The Killing Fields” the most balanced view of politics and grounded immersion, giving the film a greater sense of cohesion than perhaps Garland is able to conjure himself. Joffé is able to create a powerful sensory experience that finds its balance of message precisely in the imbalance of its characters’ degrees of separation from the war in question.

7. 20 Days in Mariupol (2023)

If “Civil War” is a film about war journalism, then “20 Days in Mariupol” is a case of the film in question being war journalism. On the front lines of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, just as it was gearing up, Mstyslav Chernov gives viewers one of the starkest, unflinching portrayals of war and dehumanization. What’s more, it’s a perspective made all the more horrifying due to its journalists being entirely susceptible to the same dangers as everyone around them at all times.

Rather than imagining a vague conflict and a sensationalized view of false urgency, “20 Days in Mariupol” is uncompromisingly bleak precisely because it refuses to pull punches, reminding us of where we are at this exact moment. Is that an unfair comparison, given that one film is a documentary while the other is fiction? Maybe, but Chernov’s and his team’s bravery gives his own film more tangibility than could ever be achieved through a fictional lens. It’s simply the way it is…

8. Come and See (1985)

And here we are, the big one. Whenever the conversation around war films veers towards the most chilling, the most scarring, and the most unforgettable, the endpoint is always the same. Elem Klimov’s “Come and See,” quite simply, offers arguably the most horrifying depiction of war ever put to celluloid, chronicling a young Russian boy all too eager to load up and defend his village from invading Nazi forces. What results is an experience that goes past conversations of sensationalization and heads straight into soul-destroying nightmare fuel.

Where Alex Garland traffics in beautifully slick compositions, Klimov gets his points across in the mucky grain of reality, as if all forms of idealism have been stripped away the moment a gun is placed in one’s hand. Though journalism is nonexistent here, the final striking image of “Come and See” (a title telling enough in itself) makes for one of the most memorable uses of a photograph in any feature. Whether you appreciate “Civil War” for its ambitions to put you in the midst of havoc or shun the film for its inability to meet those ambitions, “Come and See” makes for the most effective space to see where such goals can be taken to their most haunting, and poignant, extremes.

![I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore [2017]: Sundance Film Festival Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/I-dont-feel-at-home-in-this-world-anymore-1-768x489.jpg)

![Falling Down [1993]: The Contemporary American Downfall](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Falling-Down.jpg)