“I hate to be one of those people that gets kicked upstairs,” director James Ivory mentions (in archival footage) near the end of the meticulously presented, lovingly assembled – and somewhat more daring than others, even if still unsure in its overall strategy – documentary of US filmmaker Stephen Soucy’s “Merchant Ivory,” which is now hitting the US theaters. The first of its kind on the whole Merchant Ivory extended family (the conception of the Merchant Ivory company as a family is nurtured from the opening chapter till the film’s end credits and thanks), Soucy utilizes well the renewed interest in James Ivory.

After years of being thought of as a director of ‘costume films’ (“Room with A View” [1985], “Howards End” [1992] being the launching point of the international success of the Merchant Ivory company), James Ivory returned with a queer vengeance in the 21st century, having scripted the Oscar-awarded “Call Me by Your Name” (2017, Luca Guadagnino, based on the André Aciman novel). And he subsequently became the oldest Oscar-awarded recipient (he is now 96 years old and gladly featured in the film).

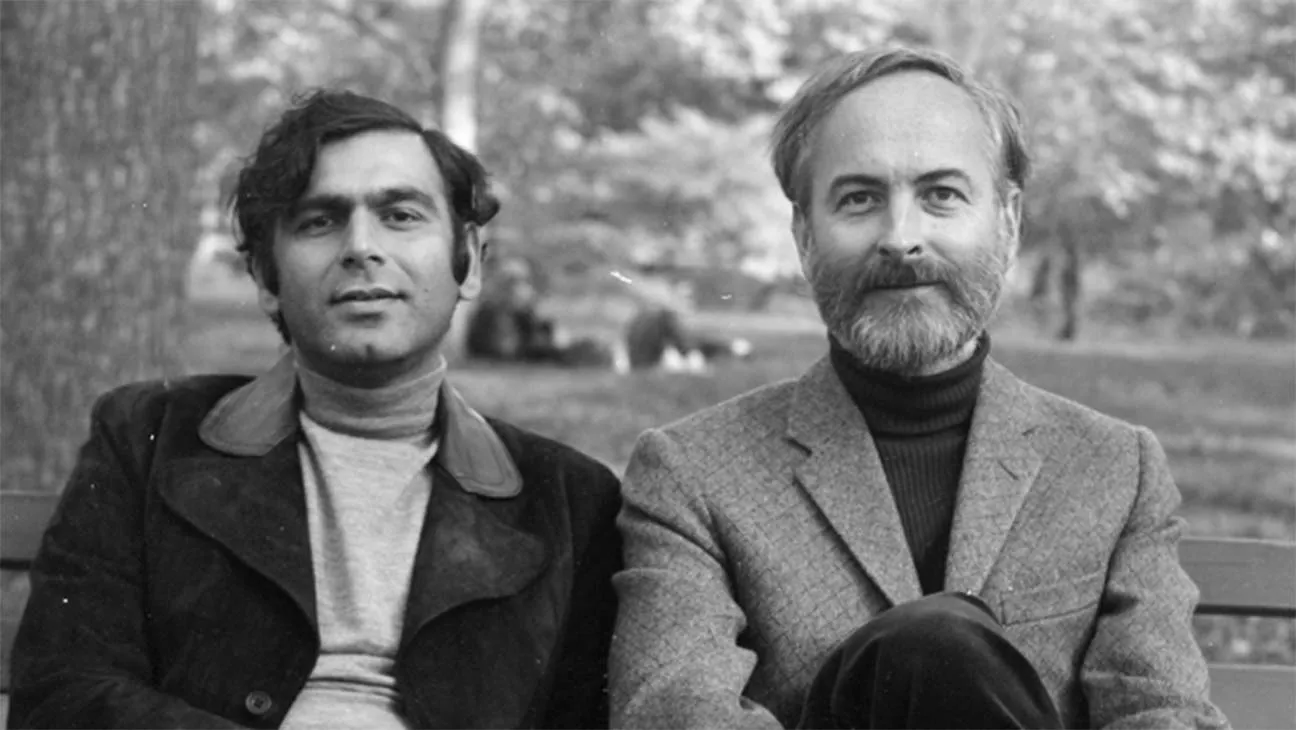

Making a homage to the many celebrated book adaptations of the company, “Merchant Ivory” employs a book-like structure by splicing its narration into six distinct chapters; many of those are devoted to each creative partner of the Merchant Ivory company, Ismail Merchant (1936-2005), Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (1927–2013), and Ivory (b. 1928) himself. Just a note: Merchant Ivory company has 43 films on its slate, a still impressive number in an age where the indie filmmaking it practiced sounded like a US happy aberration.

And a happy aberration of the guerilla-meet-theater troupe it was; the intro ‘Wandering Group’ chapter summarizes, like Ivory’s own “Shakespeare Wallah” (1966), the way the company found its way in the early years, in and out of the big Hollywood studios -with their first feature, the neorealistic-looking “The Householder” (1963), based on the eponymous Ruth Prawer Jhabvala novel, finding a surprise US distribution via Columbia Pictures.

The fascinating (and much neglected) early period of the Merchant Ivory company both in India and the US (anyone remembering Michael York and Rita Tushingham in the 1969 spiritual travelogue “The Guru”?) is rather hastily sketched out. Regular Merchant Ivory collaborator Madhur Jaffrey appears too briefly to register, and their 1970 gem “Bombay Talkie” gets an equally brief mention. Of course, everyone remembers Merchant Ivory from its first commercial and artistic success of “Room With A View” (the first of the three E. M. Forster adaptations the company filmed) that would make Merchant Ivory a household name -even to the point of almost eliminating its rich filmmaking past.

Indian producer Ismail Merchant, Ivory’s business and life partner, was the person who could make things happen. The doc chapter “The Mystic Masseur” (named after Ismail Merchant’s 2001-directed film) reveals the whole modus operandi of the Merchant Ivory company in a nutshell. Juicy statements from various participants (such as Vanessa Redgrave, Emma Thompson, and Hugh Grant) abound here; these sometimes lean too much on describing Merchant’s tactics as individual choices (a cinematic conman to ensure funding) rather than a necessity to make and complete the films, based on various haphazard money resources.

Let’s not forget that US indie filmmaking still doesn’t have the safety valve of the several European National Film Centers and Institutes regarding funding. In that sense, Vanessa Redgrave’s statement about Ismail Merchant’s “implacable determination” somehow rings closer to what the man would be, apart from preparing lavish meals for his crew when the money wasn’t forthcoming.

Even if James Ivory is overwhelmingly (and very probably faithfully) depicted as the calm yin to Ismail’s fierce yang, it is Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, the company’s longtime collaborator and screenwriter, here portrayed as the quiet power. The exquisitely talented and perceptive novelist and screenwriter (who had access to the editing room as well in James Ivory’s film) has her chapter in the Sousy doc – told mainly through her own previously recorded interviews and letters, and interview snippets with her daughter Ava Jhabvala Wood.

The trio has always been vocal about their creative process in the Merchant Ivory company in past talks and tributes. In contrast, the not always explored queer angle the documentary pursues ultimately gives “Merchant Ivory” its charm; it is the cinephile’s dream of going into the personal lives of their celebrated auteurs and finding something still unexplored (even if the film still looks rather discreet in this regard).

The Oregon-born James Ivory (perennially mistaken as a Brit) felt no qualms about his homosexuality but was cautious not to spill it out to the public till after Merchant (a Muslim Indian in a conservative Mumbai family) died in 2005. (Ivory discusses lovingly and unpretentiously his early sexual awakenings and later relationships in his 2021 autobiography of sorts, “Solid Ivory”).

“Merchant Ivory” reserves a whole chapter to the queer “Maurice” (1987), the gay Forsterian romance with a happy ending, released during the height of the AIDS epidemic. Here, the more intimate film in the Merchant Ivory’s Forster canon is getting its rightful place and both emotionally remembered and critically celebrated. (A 2018 GLAAD award appearance of James Ivory, who shared audience life-changing reactions to “Maurice” makes the point relatively solid).

And then there’s Richard (Dick) Robbins (1940-2012), the longtime composer and unsung fourth member of the Merchant Ivory company (two Academy Award nominations for “Howards End” and “The Remains of the Day” [1993]), who finally gets his due. Robbins served admirably as a composer of lush and poignant music themes, yet his involvement extended to the personal milieu of the Merchant Ivory company. His long-term relationship with Ismail Merchant becomes far from a tabloid gossip news item in the “Merchant Ivory” doc. It touches upon our contemporary open relationship idea with its difficulties as practiced by the three primary Merchant Ivory male collaborators.

Ivory himself looks (as Helena Bonham Carter correctly identifies it) immensely curious and calm in the film; he somehow verifies that his directing style (he studied architecture at the University of Oregon and cinema at the University of Southern California’s School of the Cinematic Arts) is less of an enforcer and more of an enabler at least, all actors interviewed would admire his trust-giving spirit. (Unless he finds something boring, as Emma Thompson delightfully remembers about a single “Howards End” scene).

The “Merchant Ivory” documentary is frank in its depiction of the financial troubles that faced the company almost at every step in its filmmaking, even up to the period of “Howards End” filming, and doesn’t shy away from the convoluted professional and personal relationships of its primary duo, Ivory and Merchant. It is part a primary reader for new Ivory aficionados and part an LGBT+ story with still a happy ending.

Ivory is a living legend, and “Merchant Ivory” does its best to place him and the Merchant Ivory company as one of the cornerstones of US indie filmmaking. After all these years, it is fresh to watch all its talking heads, from actors to editors to costume designers and producers, express their care for this company. It is a caring documentary, at points permeating the same solid calmness found in abundance at the Merchant Ivory oeuvre.

![United Red Army [2007] Review – An Exactingly Detailed Account of Revolutionary Zeal Gone Wrong](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/United-Red-Army-2007-768x512.jpg)

![Loving [2016]: With Great Restraint comes Great Power](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Loving-768x431.jpg)