I almost remember what it’s like to dislike a Wes Anderson movie, which was my first reaction to “The French Dispatch.” It began as my most anticipated Wes film because it was his first in live-action since “The Grand Budapest Hotel.” The anticipation was heightened by the fact that I was a massive Anderson fan.

There were his Oscar-nominated stop motion films, “Fantastic Mr. Fox” and “Isle of Dogs”, cartoons with a mature edge. “Moonrise Kingdom” was a masterful story of young love at summer camp, and “Budapest” took his meticulously designed storybook films to violent, vulgar, heartfelt, and hilarious high points. I’m sentimental for the time when going to watch this movie – my first Wes film on the big screen – which was a seven-minute walk from my house.

If artists’ relationship to their work is deeply personal, “The French Dispatch” should’ve connected to my desire to be a journalist, even if, like Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright), my experience came purely from a school newspaper. I wish to be the kind of writer to “never complete a single article, but haunt the halls cheerily for three decades.” I imagined Wes’ film like “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs”, an eccentric comedy from the Coen Brothers, which in itself is like a book containing disconnected stories about the Old West. Simply, Wes’s anthology homage to French cinema was “Convoluted but functional.”

It marked the beginning of a formally experimental yet emotionally detached era of filmmaking—one that continues to polarize audiences. So it feels fitting to journey back to Ennui-sur-Blasé, the film’s quaint, old-world town, where the threads linking its disparate stories drift through like faint wisps of Mouthwash de Menthe, buried deep within its meticulously crafted style. More than just a portrait of journalists bound by the newspaper they serve, “The French Dispatch” is also about the vivid characters they uncover and immortalize on the page—like Steven Park’s unforgettable Lieutenant Nescaffier, the stoic master of police cuisine.

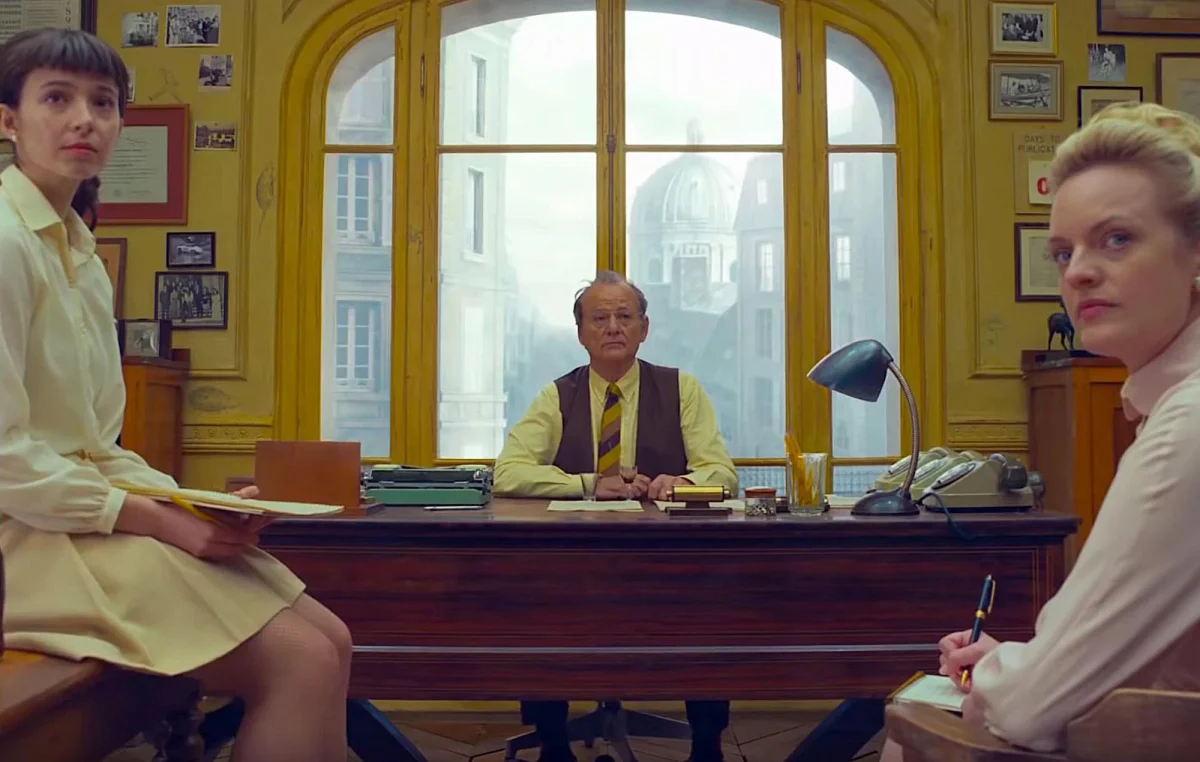

It’s a story of an editor (Bill Murray) who acts like a father to his writers. It’s about the city, with art movements that transcend law, and the young revolutionary cliques who hang out in coffee shops. There’s also cops and robbers caught in the middle of a turf war, but its best surprise is how it boldly depicts the ways that love occurs in this town.

Don’t Miss: The French Dispatch (2021) ‘BFI’ Movie Review

“The French Dispatch” is held together by themes of love and sexuality that begin faintly. The first story, “The Concrete Masterpiece,” features Anderson regular Tilda Swinton (“Only Lovers Left Alive”) as J. K. L. Barensen. She’s the kind of journalist who obsesses over one artist. (Good God?! That’s me.) Her book on Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro) is among a collection in her office. As she lectures about him, her nudes are peppered throughout her slideshow.

Anderson seeks to mine comedy out of embarrassment, but also portrays Berensten’s vanity. She breaks the fourth wall with poses that say, “I’m ready for my close-up.” They distract from the lecture as her actions covertly beg the audience to see her as desirable.

As for Moses, whose story is told in flashbacks intercut within her lecture, he’s a convicted murderer serving a lifelong sentence. Del Toro acts like a beaten dog, his head is slouched, his feet scuffle, and he growls when angry. In a twisted relationship, he’s dominated by Guardienne Simone (Lèa Seydoux). She keeps him bonded, but is also a sternly encouraging muse. She rebuffs his romantic confession after they have sex in the laundry room, so he rebounds with “The Concrete Masterpiece.”

During its notorious, long-awaited unveiling, the enlightened painter reveals that all his art revolves around one woman. Fittingly? They come out as smudged as dried body fluid. Despite the dry humor and emotional repression of his characters, Anderson ends the first episode on a sweet, wistful note. Barensen admits to her editor, “Don’t ask me to be indiscreet about what happened between me and Moses at a seaside inn 20 years ago. We were lovers, I went back to remember.“

The subsequent episode, “Revisions to a Manifesto,” has shades of Peter Bogdanovich’s “The Last Picture Show”. Obviously, both films share black and white cinematography. They also contain melancholic age gap relationships. Veteran journalist Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand) also starts a sexual partnership with her subject. Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet) is a young, suit-wearing, and chess-playing revolutionary; his parents are friends with Lucinda. They invite her for dinner, which also serves as a surprise setup with a messy professor played by Christoph Waltz (Inglourious Basterds).

Luncinda describes the uprising she’s reporting on as “A vanity exercise for the pimple cream and wet dream contingent”. Translation? They’re fighting for equal access to the girls’ dormitory. The young man gets stuck in a love triangle, where Anderson is at his most insightful, capturing the antagonism behind it. Lyna Khoudri is Juliet, the group’s treasurer. She rips the manifesto that Zeffirelli wrote, but keeps his inscription. Being a young romantic makes Zeffirelli feel like he’s among the stars. A couple of times in this section, though, young men crash back down to earth. The world of their parents’ youth swallows them whole.

The saddest of all of Anderson’s journalists is Roebuck Wright. He has a superhuman recollection of the written word, reciting one of his pieces for live TV. As for the time he got lost at a precinct during a dinner invite, he calls it “A weakness in cartography, the curse of the homosexual.” During his early days in his adopted country, he was jailed for a drunken public display of affection. His idealistic summation of the event was love. Roebuck shifts the focus of his article after a kidnapping.

Anderson once again complicates these relationships. The police commissioner’s son, Isadore Sharif de la Vilatte, or Gigi, gets kidnapped. He endears himself to his guard, a drug addicted showgirl played by Saoirse Ronan (“Little Women”). In one of the film’s most striking splashes of color, her blue eyes glow through the opening of the boy’s outhouse-like containment. Her job requires seduction, using her body as entertainment. The innocent boy sees her as she wants to be seen, so she feeds him and sings to him to calm his fear. As for Roebuck’s own imprisonment, only one man in France came to his aid.

Anderson’s new film “The Pheonician Scheme” is one of his worst portraits of flawed fathers, with the high points being Mr. Fox, Royal Tenenbaum, and the low point being Steve Zissou. Arthur Howitzer Jr is one of his best dads, but Bill Murray’s performance is so monotone and understated, plus his scenes are thinly scattered throughout, that it’s easy to disregard. He’s an editor who would rather let his newspaper lose money than compromise a journalist’s work.

In his last scene with Barensen, he’s frustrated but accepting. He gives her variations of “we have food at home” or “don’t indulge your fun using my money.” Swinton’s line readings show Barensen as an eloquent but rebellious child. Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) is like his youngest son, who loves playing with bugs. In their scene, Arthur talks like he’s helping with a science project, “Don’t you think it’s almost too seedy this time? You don’t wanna add a flower shop or a pretty place of some kind?”

Lucinda is his oldest, good at hiding her flaws. Arthur sits in comfortable silence with her, looking over her article. Roebuck is embraced by Howitzer despite being a social reject. Arthur’s demeanor calms Roebuck, and they connect over humble beginnings as journalists. During a debate about the purpose of an article, the section shows that parents and children can disagree cordially.

Perhaps the funniest thing about Arthur is that his last will is full of spelling mistakes. He doesn’t let people cry, like a dad who can’t access his emotions, but he has a family picture of his crew above the doorframe of his office. Howitzer isn’t perfect, though. The French Dispatch’s illustrators are the black sheep of the family. Rosenthaler and Arthur aren’t dissimilar either. They were born in wealth and rebelled as young men. Moses was the son of a Jewish-Mexican horse rancher who replaced privilege with squalor, danger, and schizophrenia. Arthur used daddy’s money to get out of Kansas, but their family publication became a worldly product during his tenure.

Roebuck’s article, “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” is fascinating to revisit because it evokes both “The Royal Tenenbaums” and hints at the emotional core of “Asteroid City”. Lieutenant Nescaffier, but most importantly for this article’s sake, Gigi (Winsen Ait Helall) are meant to evoke our sympathy. The latter is one of Aderson’s trademark super-talented kids; he reads unsolved cases, and his first words were “papa” in Morse code. Wes has developed a Nolan-esque habit of mentioning dead wives to deepen the bonds between father and son.

Instead of neglecting his kid like Royal, Zissou, or even Mr. Fox might, Commissaire de la Vilatte (Mathieu Almaric) runs to his aid. Through all the chaos in that story, Roebuck was most taken by a gentler moment between the pair, where they’re allowed to experience a deep wave of emotions. On the tragic side of these stories, the loss of a child lingers during a silent taxi ride on a rainy day.

As Anderson mentions, “The trouble with Anthology storytelling is that inevitably some stories are more interesting than others.” It requires audiences to reinvest in different protagonists throughout the shifting acts of the film, instead of a singular character journey best exemplified by “Star Wars.” Wes’s film neatly mirrors newspaper sections. There’s an Obituary, a brief travel guide, and three feature articles, but he makes key choices that distract the audience instead of immersing them in his film.

Along with his cinematographer, Robert Yeoman, they spitball changes in aspect ratio, or sudden shifts from color to black and white. At first, they clearly delineate how a city changed over time. In more specific cases, it heightens the hopeful romanticism that Moses feels for Simone or the intimate care that Zeffirelli has for the women taking part in the love triangle. Other times, they cause a flat image, like when Julian Cadazio (Adrien Brody), Moses’ art broker, argues about a delayed second piece. When combined with the soft-spoken, dry delivery of the ensemble, who sometimes deliver elaborate punchlines, an annoyed audience might disregard the film.

You Might Like: All Wes Anderson Films, Ranked

Anderson has his flights of fancy, through self-conscious surrealism, or his trademark play-within-a film. In a montage, Tony Revelori (“Spiderman: Homecoming”) plays a young Moses, he takes off a precious necklace, and Benicio comes on screen. Revelori puts it on his neck, a symbolic baton pass. Del Toro will lead the rest of the episode after his younger self didn’t pick up a brush for about a decade of incarceration. The second article has a flashback to a young man’s experience in boot camp.

Because it’s handled as a play (also edited by Lucinda), the scene’s core ideas of an uncertain generation of young men just picking up the workload of their family get lost in Anderson’s love of theatricality. The intergenerational conflict at the heart of the section plays out through an elaborate game of chess. The government has a couple of different forms of communication, but instead of causing laughter through complicated protocols, it confuses the viewer.

In his article, Roebuck describes the commissioner as an elite detective who adores food almost as much as his son. The section builds as the commissioner creates a rescue plan in the middle of a six-course meal. Color sequences and swirling camera movements enhance their aesthetic beauty and hypnotic taste, but the black and white section of a split screen shrinks the city-wide call for help among the commissioner’s friends. It makes his’ desperate need to find his son feel impersonal and overcomplicated.

Howitzer gets the suggestion to start the final issue of his newspaper with Sazerac’s tourism reports. At first glance, it worked best as a nostalgic reunion between the director and the actor-co-writer who, together, jump-started their careers with The Royal Tenenbaums. Owen Wilson’s character stands apart from the film’s three main stories—he doesn’t change, doesn’t show much emotion, and at first seems almost expendable.

But on a rewatch, his purpose becomes clearer: he foreshadows what’s to come, sketching a fleeting portrait of a city whose quirks and contradictions the rest of the articles flesh out in detail. He shows us “altar boys half-drunk on the blood of Christ” chasing old townsfolk with sticks—figures he classifies as people for whom life has already slipped by. In contrast, the young radicals in Manifesto tremble at the thought of failure. As he narrates tales of stray cats prowling the city rooftops, we hear the café below spilling out Tip-Top, the favorite tune of Zeffirelli and his rebellious friends.

Indeed, the miniature of “The Grand Budapest” has become a classic piece of movie memorabilia. The French Dispatch, a newsroom at the center of the city, is beautiful in a top-down way, instead of the pink, giant cake vibe of Anderson’s most revered establishment.

One of these miniatures is the prison asylum where Moses is serving his sentence. As the sun sets, gigolos and streetwalkers replace the daily working class. Women with red lipstick, erotic outfits, and overdone hairdos hint at the drugged-out showgirls in the final section.

As Sazerac questions, “What sounds will punctuate the night,” screams and gunshots foreshadow the action-packed but stately aspects of Robuck’s experience in the field. The opening article is the film’s most obvious homage to Jacques Tati, where every moment builds to a sight gag. The worlds of both directors exist in a place between life, theatricality, and cartoon.

Most of Arthur’s people are expatriate journalists who unite in their grief to write a summation of his life. For one of Wes’s worst and coldest films, its ensemble is deeply lonely. Before he starts painting again, Moses resorts to poisoning. “He’s literally a tortured artist” who finds genuine kinship with Simone and takes up pottery and basket weaving. Lucinda’s loveless life is considered sad by her friends.

The mousey, no-nonsense woman projects strength and individualism, but wipes her tears in the bathroom. This is the first time she sees Zeffirelli naked. When asked why he always writes about food, a shift to black and white accentuates Roebuck’s chilling confession, “I’ve often shared the day’s glittering discoveries with no one at all.” He’s come to appreciate the cuisine around him and the people who were there to serve it. While Barensen isn’t exactly lonely, she is a wistful attention seeker.

Calling movies a love letter to recurring ideas is overused. Is “Jaws” a love letter to menacing POV shots, or “Nashville” a love letter to charming, offbeat southern folks? Instead, Anderson expanded upon Mr. Gustave’s strange sexual preferences to explore the passionate romanticism of an entire city. He’s a man nostalgic for the tactile tools that create art (the pages of a book, theater performers, walkmen, and jukeboxes), but his own artistic changes are happening along the margins of his stories. Admittedly, it’s a periphery that also made his latest film crumble as you try to grasp it.

Anderson’s love of art is taken to confusing extremes in “The French Dispatch”, perhaps causing apathy and boredom among audiences. Still, Jeffery Wright found every ounce of sympathetic humanity within the boundaries of Anderson’s newspaper, one whose spine is glued by a scattered reflection of (mostly) compassionate patriarchs.

On top of that, Wes, the expatriate living in France, is still using “French New Wave” techniques to endear us to imperfect dads. Seeking something that was missing, this film fit Martin Scorsese’s definition of cinema. In the fast-paced world of Internet Journalism, art should remain humane, flexible, abstract, and personal, so that you can come back to it and find new things to appreciate.