Miu Miu, founded in 1993, is an Italian high-fashion women’s clothing and accessory brand and a fully owned subsidiary of Prada. Led by Miuccia Prada and headquartered in Milan, it has occupied popular culture for more than three decades, ruling runways and the sartorial imagination. Since fashion and cinema have always been intertwined, Miuccia Prada and her team led the way by commissioning some of the finest female filmmakers around the world to make short films for Miu Miu. This was, however, not just meant as a stark brand endorsement but an opportunity for each singular voice to define a story by incorporating outfits in the way they deemed culturally and aesthetically significant.

On that front, the flagship edition of Miu Miu Women’s Tales commenced in 2011 with two films on an annual basis. From Agnes Varda’s Midas touch (“Les 3 Boutons”/ “The Three Buttons”) to the contemporary voices of Mati Diop, Alice Diop, Janicza Bravo, and directorial efforts by accomplished actors like Chloe Sevigny and Dakota Fanning, the series has moved forward for fourteen years with a graceful rhythm of its own, untouched by the male gaze. In a nutshell, these shorts celebrate femininity, womanhood, and the power of storytelling in sublime, unhurried tales of identity and modern consciousness.

Here, I share 10 Miu Miu Women’s Tales that showcase the best of this unique blend of sartorial and narrative creativity, boasting a diverse range of perspectives. They are also all buoyed by evocative cinematography.

1. The Door (2013)

Given this auspicious pedigree under which women filmmakers thrive as auteurs of their own pithy worlds, “Selma” director Ava DuVernay understands the assignment of marrying glamorous images with an emotional center. In “The Door,” beautiful outfits and elegant women occupy the frames as a brilliantly cinematographed Los Angeles home reveals female kinship through a considerable period of time. Gabrielle Union is the woman enduring grief and heartbreak. Her friends exhort her to come out of her shell, and each costume put out for her traces her journey of coming back to life with a more enthusiastic frame of mind.

The most striking images are of Gabrielle being in the company of a singer who performs a swooning ballad, reiterating classic R&B music video vibes, and her moments spent with Alfre Woodard, who plays her mother, lending grace to her present emotional state. Memories of Gabrielle in a white dress blur and then come into focus. A new beginning is sought. Marrying music with images, “The Door” also gives African American women the space to revel in sartorial beauty and kinship rarely afforded to them in the annals of popular culture.

2. Spark And Light (2014)

A spark of kindness can go a long way in restoring one’s faith in the human world. Especially when thoughts of a loved one’s mortality occupy the mind’s upper firmament. As is common in the liminal spaces that constitute our living moments, faces and places often blur or morph into other physical entities when the subconscious takes over. A world of dreams, hence, gets conceptualised by So Yong Kim here as a birthday party, a kind woman sheltering a distraught daughter, a hospital bed, and a snowy landscape, which punctuate the emotional terrain of female kinship.

Crucial to understanding this film’s thematic significance is its lighting. Red, green, and yellow punctuate the haze of memories. A birthday cake emerges. A group of women presides at the party. Laughs and warm smiles are exchanged. An ambulance keeps its vigil in the protagonist’s vision. Then a faint glow is seen as the daughter sits by her mother’s side in the hospital. All of these lighting cues tell us that a single life is sometimes beyond plain reminisces. It can be a point where present and future anticipations can arrive at the same place.

A mother-daughter bond is at the heart of “Spark and Light”. Riley Keough plays the young woman whose care and concern design a stirring dream vision where maternal nurture and womanly instincts come together to light the way in a crucible of memories.

3. Hello Apartment (2018)

First-time director Dakota Fanning, a prodigious figure who has always been in front of the camera, has a knack for evoking moods through her colour palette and understated musical cues. Eve Hewson plays the young woman who moves into the titular apartment and finds friendship, romance, and the singularity to be herself in a space of her own. The solitary moments where she paints a still life, observes her home, and goes inward are strikingly real. It’s the “room of one’s own” paradigm made sensitive and seen from a distinctive lens of youth and the flowering of the Self, even when one is in the middle of a gathering.

While the location is never specified, the apartment or loft has a certain freedom of space that lets us see Eve be at the helm of different emotions. It is here that she throws parties for friends. It is where she meets a boy and experiences her first intimate connection. Moreover, it is here that she realises that the relationship doesn’t hold a bright future. It’s also right here that daylight and dim bulbs reflecting her nocturnal space inform her that the best parts of her life are not in the company of others but with herself. She eventually leaves the apartment.

The remnants of spilled wine on the floor and walls then make a poignant appearance as an older woman looks around the apartment and mouths the titular words. It’s a home’s journey traced through two women who experience life and its private reservoirs of joy and self-definition in pivotal ways.

4. Brigitte (2019)

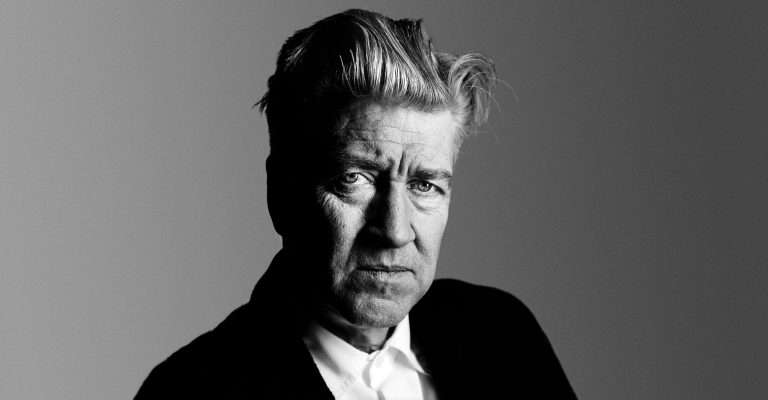

By now, it has become a concrete fact that nobody can evoke imagery and a certain mood pertaining to the human experience quite like Lynne Ramsay. As her latest feature, “Die, My Love,” continues to make waves worldwide, it’s a good point of cultural identification to look back at this beautifully evocative documentary short on acclaimed portrait photographer Brigitte Lacombe.

First and foremost is the black and white cinematography that renders each image with stark clarity, further emphasizing the importance of the camera for its subject and her respective muses. Still images, dynamic yet smooth dolly shots, and close-ups capture the process behind the perfect ‘click’ with thematic resonance.

With Brigitte’s beloved sister and creative partner, Marian Lacombe, occupying a central place within its runtime, this short film literally becomes a valentine to a lifelong sisterhood further interspersed with unobtrusive narrations and photographs from the Lacombe siblings’ youthful heyday in America. There’s an ease to the progression here. With Lynne’s unique points of view, the spirit of creative collaboration becomes meta and utterly memorable.

5. In My Room (2020)

The most inwardly evocative of all Miu Miu Women’s Tales, “In My Room” finds “Atlantique” and “Dahomey” helmer Mati Diop excavating her familial legacy while painting an impressionistic portrait of the era of lockdown. From her apartment in Paris, she views the world in a whole new light. As is her wont with her eye for documentation, she observes the movement of human bodies in other flats from a considerable distance — almost like watching shadows — letting her grandmother’s words of alienation and wistful charm punctuate long takes of curtains billowing in the wind, the city skyline, and the setting sun.

Within this muted world of recollections, she lip-syncs her kindred’s favourite opera while clad in a glittering Miu Miu dress, exchanges emails with the Prada team, and unveils the locus of memory, locating her place in the world, especially in an instance where her grandmother, stricken by the fear of abandonment at the end of her days, breaks down. By withholding her facial or actual presence from the final work, a haunting residue permeates “In My Room,” mixing individuality and age-old concerns of kinship with an elegant analogue touch of creative freedom.

6. Shangri-la (2021)

If you have been won over by Isabel Sandoval’s affinity for evocative cinematic history in her short film “The Actress,” where she embodied iconic female characters from “Blue Velvet,” “Morocco,” and “The Tree of Life,” et al, “Shangri-La” will once again arrest your imagination by its social commentary and historical perspective.

Centring its confessional narrative of swooning desire and interpersonal relationships around the miscegenation laws of 20th-century America, two secret lovers open up their hearts to each other. A female perspective brings erotic pulse and internalised heft to her tale. The Miu Miu outfits then become instruments of sensuality where the entire courtship centres itself on the power of words, the couple’s distance manifesting itself in their imaginations, dictating their soulful union.

A single touch is never exchanged among two lovers, but their bodies seem to transmute the present circumstance to become vessels of transference, carrying their desires towards each other. This absence of corporeality makes their bond full of yearning. It is also quite raw in its delineation, which not only captures the remote contours of working during the pandemic but also serves its purpose of being at the threshold of fantasy and reality.

“Shangri-La” often references a supposed utopic place where dreams come true. The irony of the title is in the ultimate realm of a private vision here. It is poetic and sufficiently complemented by music and yearning looks, but never skirts the lines of ribaldry. Hence, Isabel is here to present an idea of love and longing that is deeply personal.

7. Eye Two Times Mouth (2023)

“Eye Two Times Mouth” is triumphant primarily because of its casting choices. The lead protagonist here is a Mexican woman (Akemi Endo), her musical mentor, friend, and singing tutor is a specially abled man (Alan Pingarron), while her diction and mannerism coach is a Japanese/ Latinx polyglot (Irene Akiko). Their cumulative efforts are in the direction of producing a favourable audition for the opera Madame Butterfly.

By making Akemi’s perspective colour the conversations and training routine, “Eye Two Times Mouth” becomes an exercise in understanding the sheer aesthetics of one’s evolving artistry, away from the dictated semantics of elitism that seemingly govern such forms as opera or art galleries. She is the anchor of humility whose ambitions get under our skin.

As viewers, we root for the young woman who patiently divides her time as an invigilator in an art gallery section and devotes her waking hours to being the best artist she can hone herself to be for a life in theatre. She exhibits a restrained body language, and the minutiae of her expressions pair well with the tone of the film overall.

The support of her friends and fellow creative minds lifts her spirits, ultimately producing a dazzling audition where all that she learned alchemically comes to fruition. Accomplishment is, after all, no one class’s domain. It is realised here beautifully in “Eye Two Tims Mouth.” It also helps that instead of revealing the result of her audition, the moment of onstage freedom culminates the film. In that one moment, she transcends the lines that held her back.

8. The Miu Miu Affaire (2024)

True to the best mysteries, Laura Citarella’s “The Miu Miu Affaire” has all the ingredients of intrigue. There’s a small town, quirky characterisations, a global supermodel’s arrival, her sudden disappearance, and the dogged detective intent on following the trail of clues and red herrings. What is truly admirable about this particular slow-burning narrative is that the Miu Miu dress actually generates its central mystery in the pursuit of a beautiful young woman who is seemingly lost in a strange backwater town.

Superstitions and local mindsets enter the picture. A red dress that the supermodel wears leaves a trail down a rabbit hole of secrets and suppositions. Her identity as a paragon of glamour also lends itself to assumptions about the nature of her living arrangement in the hotel. In a way, as a single, working woman, she is an anathema to the townsfolk, a larger-than-life figure who doesn’t actually fit into their limited purview.

Far from the typical Hollywood trappings of pitch-perfect presentation, the people look and behave like everyday individuals, while there’s a genuine haunting tone in the unraveling here. The final images are bound to stay with you without providing any real closure. Once again, it’s the women who rally together to find the truth. Since this short is cut from the same cloth as Laura’s recent picture “Trenque Lauquen,” it serves a greater narrative centred on small-town behaviour and a bona fide detective drama.

9. Autobiography Of A Handbag (2025)

We accord so much value to inanimate objects sometimes that it becomes refreshing to see the world through one such item’s perspective. With a hauntingly evocative voiceover and unique point of view shots, Joanna Hogg makes a Miu Miu handbag observe human nature.

She is first gifted to a teenage girl hailing from an affluent Italian household. A lout then sells her on the cheap as some kind of knockoff. She then finds herself in the possession of a young woman in an unhappy relationship who leaves her on the train. Eventually, she finds her way to the beautiful Italian countryside, where natural beauty and rain accompany her interior thoughts. Before her solitary state informs the flashback structure permeating the screenplay, she enjoys some tranquil moments flanked by a group of young travellers with their musings on the world, informing her thoughts with a sense of comfort.

Not only is the conceit full of promise, but it is executed with the right wistful tone. When the handbag, especially, is stacked with a gun and is held in a police station, her perspective grasps the dangerous ways of human actions. Throughout, the sense of consumerism and capital associated with a Miu Miu handbag is countered by its humane personification in this instance. The most interesting aspect is that the film begins with the handbag referring to her “mother”; maybe in this clever way, Miuccia Prada’s influence is being acknowledged here.

10. Fragments For Venus (2025)

Alice Diop employs her own voice to elucidate cultural erasure from her distinctly individual lens. By looking at artworks celebrating Caucasian representation and then presenting Black bodies on the margins of these paintings, dating back many centuries, she uses the camera to register the way dominant voices stifle other bodies and personalities by dint of prejudice and specifically colour bias. Even in representation, the faces and bodies are either servile or titillating.

Kayije Kagame (“Saint Omer”) observes this cultural churning with a Zen approach inside the Louvre, while Sephora Pondi revels in looking at the individuality of Black women engaged in everyday rhythms around Brooklyn, free from the male gaze or the white person’s burden of giving them a legible space of their own. Some women eat, others share laughs. A traffic police official exhibits effortless flourish while handling her day’s work, while a woman creates art on a park bench. A dozen or more women ultimately pose with Pondi for a portrait, capturing them in all their diverse hues of Black womanhood in Miu Miu outfits.

I loved the way “The Lorde said” referencing Audre Lorde’s seminal words, shorn of academic polish, closes the film. It’s a solid cultural moment of revision and reclamation that’s also boldly feminist. Art and culture may be intertwined, but prejudices prevail. This work that unites a diverse range of Black women rectifies that overarching narrative.