The Czechoslovak New Wave sparked in the 1960s in Czechoslovakia that helped enable cinema as an art and form of communication in the region. It significantly revolutionized the medium as a means of expression more so within the philosophy of film and ideology of visual narratives through its idiosyncratic imagery, radical concepts, and politically aggressive themes. The conception of the film movement is primarily due to two major reasons- the establishment of a film school in 1947 and the De-Stalinization of Czechoslovakia in the 1960s. This resulted in the birth and development of artistic notions along with sound technical abilities, the two sides of the non-conformist creative conscience as the heavily reliant fulcrum.

The film movement’s distinguishable characteristic is the feisty tonality irrespective of the genre, subject, or narrative. The zealous urge to express is conspicuously crafted in every film from deadpan humor to dry and brittle drama. The themes that these films primarily explore are warfare, conservatism, consumerism, social identity, and ideological conditioning. The essential filmmakers of The Czechoslovak New Wave include Věra Chytilová, Jiří Menzel, Jan Němec, Miloš Forman, František Vláčil.

The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1962)

A Sci-fi mythology set in the 20th century about man’s first landing on the moon while discovering an already existing feudal colony administered by Baron Munchausen. Tonik the astronaut, along with Baron and the princess is set to travel ancient Earth in a retelling of classic stories of love, romance, rescue, envy, and dreams in meshes of yellows, reds, and blues.

Related to Czechoslovak New Wave: 10 Best Sci-Fi Movies of the Decade (2010s)

Moving on the planes of surreal and absurdist fantasy dramas. The visual treatment is very reminiscent of Japanese avant-garde cinema, particularly Nobuhiko Obayashi albeit with significantly distinctive sensibilities. The film very rapturously captures mythical settings, stories not just as informative sequences but stunning mood pieces. Incorporating stop motion animation that radiates in pastel color palette and extremely photographic cinematography that very literally symbolizes “Every Frame a Painting”. The Fabulous Baron Munchausen is not only one of the most visually unique films but one of the most underrated films of a creatively effervescent film movement.

The Sun in a Net (1963)

Life’s metaphysical correlation with reflection is at the forefront of Štefan Uher’s early 1960s masterpiece. The film renders visually reflective components, striking beams of ideas upon the thematic elements of youthful exuberance, compassionate love, adolescent relationship dynamics, existential wandering, solitude, and hands; amidst the palpable locale that, from time to time doesn’t fail to enchant the ever mischievous, hypersensitive camera.

What provides The Sun in a Net a floating cushion in the ever-expanding ocean of great films is its uniquely crafted cinematic treatment and auditory wonderment. The film intermittently intermingles with narrative voiceovers over its visual progressions, layered with metaphorical notions- both through dialogue and character enactment. The sonic input’s singularity is in its extreme elaboration wherein the very no wave, indeterminism-Esque string, and drum arrangements effortlessly blend in and out of tangible sections of the film. The Sun in a Net is one of the most gorgeously shot films, both aesthetically and philosophically, maintaining its distinctiveness in a film movement that is known for its splendid visual experience.

Diamonds of the Night (1964)

Jan Němec’s 1964 feature is a remarkably ambitious outing presented as a crackling narrative in its portrayal of two boys that flee amidst their transport from one concentration chamber to another. The opening shot in a very reminiscent Dardenne Brothers-Esque introduction catapults the viewer right into a trembling camera that establishes the disoriented woods and the two boys escaping the disjointed frame. In the ongoing sequence of the external comatose, the uncut shot closes into the characters in an attempt to arrest the inwardness that follows throughout the film.

Related to Czechoslovak New Wave: The 20 Best French Movie of the Decade (2010s)

“Diamonds of the Night” bravely displays imaginative sequences of memories, leaping back and forth within its timeline but visually always progressing. Never resorting to pedagogic sensibilities, within no time the film presents itself as an eloquently sensitive mood piece that focuses devotedly on the feeling of such an exasperating journey, translated into sound and image. From time to time, Jan Němec captures faces meshed in rural backdrops squashed in harsh blacks and whites with realistically no dialogue sprinkling illusions and metaphors throughout. Stylistically unique with a powerful visual narrative, “Diamonds of the Night” stands tall as one of Czech New Wave’s mavericks and despite its political context, provides a deeply sensitive and emotive cinematic experience.

The Shop on Main Street (1965)

The Shop on Main Street is an overwhelming tale of an apprehensive carpenter Tóno, living in Nazi administered Slovakia, stuck in a moral quandary that keeps masking itself with new faces as the narrative progresses. Right after the credits roll, the political seatbelt is thrust upon us, “Following the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Hitler’s army and the declaration of a Slovak state, one of the first political acts of Tiso’s regime was the voluntary acceptance of the Nuremberg race laws. The year is 1942…”.

With the introduction of a senile, endearing Jewish lady to both- the viewer and Tóno, the film glides into a utopian seating in a neorealist plane that strangely deals with the political subconscious, enticingly. It takes multiple routes of deconstructing identity, showcasing ideological turmoil on numerous plateaus- personal, cultural, and socio-economical all over its political landmass. The last act of the film squeezes the plot and stretches the conflicting characteristic boundaries through an extremely memorable and humanistic drive.

Loves of a Blonde (1965)

Czech New Wave’s most popular filmmaker Miloš Forman’s most formidable work before moving to bigger ventures in the United States with Once Few In a Cuckoo’s Nest, Amadeus, and Man on the Moon. Loves of a Blond is a satirically charged film loaded with a political subtext, centered around Andula, an adolescent woman, and her dwellings. Although the first half of the film explores the socially constructed gender normative, archetypal relationship, youthful romance, and complete disintegration of the feminine identity with Andula being a part of the thematic centerpiece.

Related to Czechoslovak New Wave: Loves of a Blonde (1965): When Politics Invade Youthful Romantic Impulses

Like other Czechoslovak films from the time, visual narrative is at the fundamental core with the progression of plots, concepts, and ideas. The frames seep into the seldom brief intimate moments however abandoning voyeuristic lenses. Sonically, it enhances and brightens the arid color pallet with isolated dreamy guitar sections, juxtaposing emotionally exhaustive and agitating sequences with vibrant brass and piano arrangements.

Daisies (1966)

Věra Chytilová’s 3rd feature film and arguably Czechoslovak New Wave’s most prominent film is Daisies, a raging ideological deconstruction of the female identity in a patriarchal society. Consisting of two young women as protagonists who embark upon a mystical journey challenging authority and authoritative philosophies. The anger and powerful sentimentality against any kind of conformity are ubiquitous throughout the film.

Topically, Daisies references the stereotypical appropriation of women, their role, and functioning within societies through absurdist slapstick lenses. The mise-en-scène in the symbolically farcical dialogue, heavily expressionistic set designs, and long unshackled framework. The film moves into tangential substantive territories of equal significance- consumerism, exhibitionism, and materialism often juggling within enticing color pallets. A remarkable student in the school of Cinéma vérité, Daisies holds a strong place as one of the most visually ferocious and monumental achievements of the 20th century.

Closely Watched Trains (1966)

All of Czechoslovak New Wave’s fundamental concepts and themes culminate in Jirí Menzel’s 1966 film Closely Watched Trains. The adolescent sexual fascination of a young boy, who, following his descendent line of work as a train watcher. Set in the fervently charged backdrop of Germany occupied Czechoslovakia during the 2nd World War. Protagonist Miloš Hrma’s youthful exploration of romance and sexual insecurities very explicitly crosses pathways with the politically steered era.

Similar to this Czechoslovak New Wave Film: They Live (1988): A Biting Satire on Modern Society

The film very vehemently highlights the systemically eternal class struggle, disadvantageous power dynamics amongst the line of workers within the hierarchy. It sprinkles pungently scented ideology of the objectification of women throughout the romantic and sensuous sequences. The disconcerting themes are parched and dried in sardonic yet tasteful humor, extremely devoid of sensationalism while being prominently elucidative in nature. The plaintive revelations of the film are treated with the trademark absurdist philosophy of the Czechoslovak New Wave. The narrative very consciously loses track of a free fall in one of the most overwhelming and apocalyptic final few minutes ever put to screen.

Marketa Lazarova (1967)

Marketa Lazarova revolves around a family and their respective clan set along with the transition from paganism to Christianity. Located in an obscure village amidst vast glacial landscapes and barren weather conditions. Driven less by a formidable storyline and more by atmosphere aligned with its thematic treatise- class struggle, brutality, female oppression, superstition, authority, and familial dynamics.

The greatest achievement of František Vláčil’s masterpiece is the singularity in terms of cinematic experience. The film constantly steers on an elevated curve, feasting on explorative symbolism with respect to religion, metaphysical existence, and spirituality not only as comprehensive concepts but as captivating visuals. Condensed and macerated in choral and gospel music that magnifies the incorporeal nature of the film. Marketa Lazarova is exemplary of how powerful, transcendental, and enlightening cinematic experiences could get and is one of the greatest films ever made.

The Cremator (1969)

One of the most uniquely crafted films while being ideologically revelatory and challenging is Juraj Herz’s The Cremator. Revolving around a protagonist who works at the crematorium. The film fully devotes itself to experience and exploration, partaking in various aspects of human life- philosophy, social conditioning, spiritual profundity, absurdity, and belief systems with relation to one another at different intervals of time in one’s life.

Related to Czechoslovak New Wave: The Cremator (1969): A Macabre Masterpiece

The Cremator explores Mr. Kopfrkingl’s evolution in a short period of time. His fascination towards the aftermath owing to his work, loquacious sequences of his conceptual understanding and appreciation of art, special inclination towards the philosophical in-depths of Buddhism. The cinematic language is characterized by equally fascinating choices with rapid intercutting montage sequences designed over gospels and restrained fixtures in dialogue exchanges. It incorporates extremely wide frames in rare intimidating moments intermingling with metaphorically charged claustrophobic images. Rudolf Hrušínský’s anomalous expressiveness and body language immensely complement the film, in one of the most remarkable performances witnessed on screen.

Pictures of the Old World (1972)

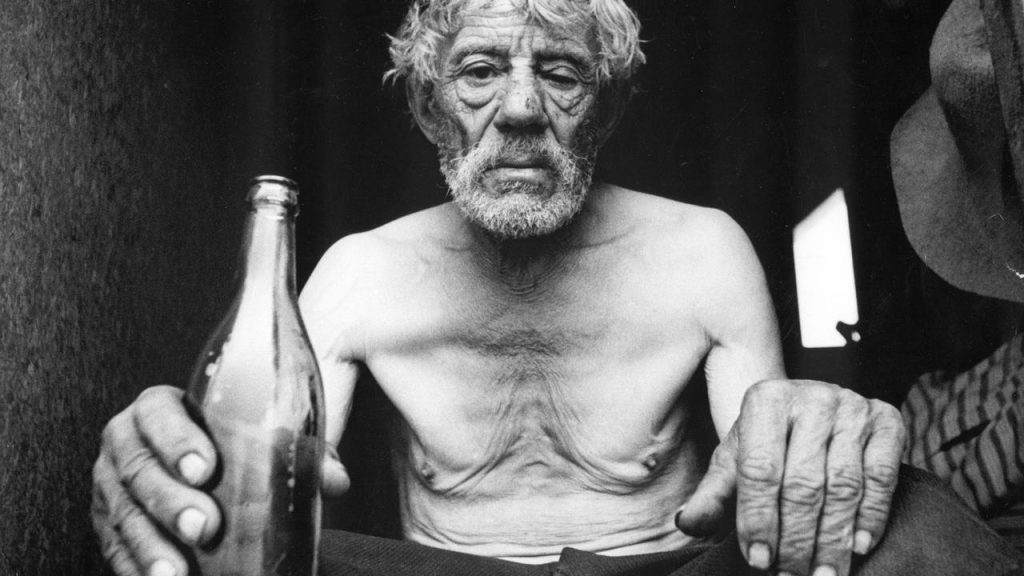

“These are stories of people rooted in the soil they came from. They cannot be replanted, they would perish.”

“Pictures of the Old World” titularly is a literal manifestation of sound over image through its short but transforming run time. The film opens up with distorted ambient bells splurged onto densely grained monochromatic photographs. The subject of the film in its entirety remains fiercely unidimensional- people commuting into their origin, experiences, philosophical discourses, ideological sermons, and political ramblings that seep through metaphorical tunnels and recited poetry.

Dušan Hanák’s underseen masterpiece stomps layers upon layers of snippets and images of people, places, objects, animals, house dwellings, arid sandscapes, and vast barren lands interweaving existential monologues and idiomatic songs in the film. A purely atmospheric piece that never shifts from the prosaic visual treatment of the film. The symbiosis of staggering images and insistent soundscape elevates the percipience, sensibilities, and the amalgamated experience of the film converging into the incessantly attempted but rarely achieved universal oneness of the human condition. “Pictures of the Old World” holds a special place in being one of cinema’s great miracles, albeit a silent one.