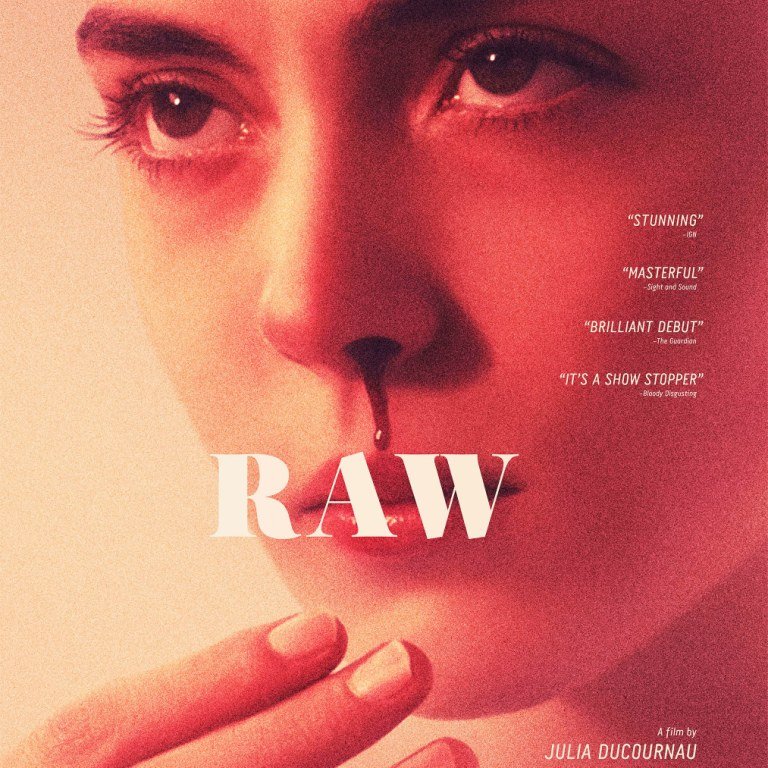

All the institutions in our society jab at the principles we live by. While the alleged democratic society champions’ individuality and the need to express freely, the reality either forces us or teases us to step a little outside the boundaries of our principles or rules. Sometimes that little step may crumple one’s world. The peoples who step on our lives and the institutions that bestow us with an outsider status just want us to stay in line: to confirm and submit. Yet within this fascistic structure which invades and distorts one’s individuality, the older generations look up to younger generations to find the ‘solution’ for the past mistakes. Of course, one needs to compromise their values to happily co-exist or blend in with the society. But what are all the means and ends we implement and achieve in this prolonged ritual to be part of the society? What if you shed your self too much in the effort to blend in and don’t recognize yourself anymore? And why do the institutions always give us raw medicines to bite upon and swallow? French film-maker Julia Ducornau’s spine-tingling piece in the body horror sub-genre Raw (aka ‘Grave’, 2016) presents us with similar contemplative questions (on conformism, coming-of-age, sexist socialization, etc) to chew upon.

The protagonist of Raw is Justine (Garance Marillier), a virginal, introverted, idealistic 16 year old girl, who is enrolled at a prestigious veterinary school, where her parents (Laurent Lucas and Joana Preiss) studied and elder sister Alexia (Ella Rumpf) is currently studying. Justine is about to be dropped off at the college by her parents. They are vegetarians and they stop at a cafeteria. Justine asks for mashed potatoes. She finds a meatball in it. It kind of signals the array of tests Justine is about to face in order to compromise her set of values. Justine’s tension to encounter the new adult world is visible. She early pushes away the dog that licks her face, but holds on to the pet when the menacing buildings of veterinary school rise up on the horizon. Although Justine has asked for a girl as roommate, she is assigned a guy named Adrien (Rabah Nait Oufella). Adrien reassures that he is gay. Soon the fraternity or hazing ritual begins. The seniors, covering up their face like terrorists, wake up newcomers in the middle of night, throwing up their beds outside the windows.

In one perfect shot which portrays the bullying and symbolizes what’s to come, we see students in their night dress on all fours, slowing crawling through the car park. Later, in a sequence which briefly reminds of Carrie, Justine and her classmates are doused in blood. Another part of the ritual is to eat a little lump of unidentifiable raw meat. Justine avoids, stating ‘I don’t meat’. Alexia (an exact opposite to Justine’s personality) intervenes and forces the meat into her mouth, assuring how these are the things she must do to be part of the group. The difference between the hazing ritual in Raw and countless other Hollywood comedies is that director Ducornau’s staging hums with palpable sense of fear. The near-surreal ritual sequences perfectly zeroes-in on the pressures faced by Justine. She is caught between the will to embrace her sexuality (in order to follow the path set by Alexia) and continue her legacy as the weird, awkward Grade-A student. Isn’t college all about experimentation and a space to get out of our parents’ shadow? But how much of this experimentation stands between the definition of normal and outrageous? Justine is torn apart by such thoughts as the little piece of raw meat she swallowed has already initiated a unquenchable craving.

Director/writer Julia Ducornau has given heavy emphasis on crafting a robust visual language, where without the presence of explanatory dialogues we can precisely understand the character’s physical and mental transformations. An assortment of interesting visual details helps Ducornau to achieve such a language. For example, the early party scene ends with Justine finding Alexia and walking out of the claustrophobic space. The shot cuts before showing a hanging stuffed fur sheep, may be to indicate the end result of hazing (to follow someone like sheep) or to symbolize the upcoming change of vegetarian Justine. The fear the horse feels as it is put to sleep is linked with the instinctive fear plaguing Justine. Then there’s the shot of Justine dreaming about muscular black horse racing on a treadmill and later Justine fantasizing about her gay roommate’s body (as he is playing football), representing her blossoming womanhood.

Although Raw would be best known for its meat-chewing scenes, Ducarnou instills tension and sense of dread throughout the narrative. She avoids jump scares, but even films simple sequences by incorporating tinge of macabre elements (for eg, the withdrawal scene depicting the agony from inside the covers, which is as impactful as the scene in Trainspotting or Christiane F). The bold, striking visual palettes reminds us of the works of Italian horror masters and the unsettling body horror sequences brings to mind Mexican film ‘We are What we are’, Canadian horror ‘Ginger Snaps’, and Cronenberg’s oeuvre. Despite such little thematic or visual similarities, Raw never feels derivative. It has a very distinct visual language which juxtaposes the beautiful and grotesque actions of the characters with equal elegance.

If stripped of the extreme horror factor, the dilemma faced by Justine is something we all face: to either surrender to the primitive urges (related to carnal pleasures) or just embrace the pre-existing moral principles. In Ducornau’s hands, Justine is shown as more than a passive character. She progresses to achieve orgasm and finds immense pleasure in gorging the flesh, but then she doesn’t want to totally succumb to the primal instincts (like the sister Alexia). She descends to animalism, yet the strong sense to differentiate between right and wrong ails her. The other interesting aspect Ducornau brings to the tale is the unique female gaze. While woman’s bodies are glamorized or sexualized on-screen, the director puts forth Justine’s sexuality in unapologetic ways. There’s something raw in the depiction of Justine’s body. She starts off as a cute-looking, awkward teenager, but gradually we face the trivial changes in her body – from skin peeling to puking, peeing, waxing, sweating, biting and the presence of dark rings under eyes. By showcasing Justine’s de-sexualized body, Ducarnou transcends the cinematic boundaries of the word ‘feminine’ (often related with one-dimensional compassionate women characters).

Raw (98 minutes) is yet another audacious and unsettling horror film that doesn’t shy away from making a profound social critique. Although the cannibalistic element in the narrative would be biggest talking point among viewers, its unparalleled taboo-breaking female perspective doesn’t go for cheap sensationalism.

★★★★

![Creed [2015]: The Discreet Charm of Balboa](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/635712555627482823-XXX-CREED-SNEAKPEEK-MOV02-DCB-74168496.jpg)